Sigourney Weaver’s 10 Best Movies

We look back at the best-reviewed work of the A Monster Calls star.

Sigourney Weaver’s distinguished career includes three Oscar nominations, more than $2 billion in lifetime grosses, and roles in a pair of James Cameron-helmed sci-fi franchises — not to mention an impressively eclectic array of films that runs the gamut from serious dramas to ribald comedies and back again. This weekend, she’s back on the big screen with A Monster Calls, which expands into wide release, so we decided to pay tribute by taking a fond look back at some of her brightest critical highlights. It’s time for Total Recall!

10.

Career advancement often has as much to do with who you know — and your gender — as the quality of your work. It’s a sad fact that’s handled with a light touch in Mike Nichols’ Working Girl, a sharply written, solidly cast romantic comedy starring Melanie Griffith as a secretary whose acumen for investment banking is ignored at her firm because she didn’t go to the right school. Using an injury to her boss (Sigourney Weaver) as an opportunity to make her move, she proves her hidden potential — while falling in love, of course, with an executive (Harrison Ford) who doesn’t know she’s “just a secretary.” Portions of the plot seem dated now, but in its day, Working Girl offered audiences a bright blend of screwball comedy and social commentary. As Rita Kempley wrote for the Washington Post, “This scrumptious romantic comedy with its blithe cast is as easy to watch as swirling ball gowns and dancing feet. But oh me, oh my, how much more demanding it is to be a fairy tale heroine these days.”

9.

Rich with ambiguity, dark secrets, the looming threat of violence, and a hint of domestic dischord, Ariel Dorfman’s play Death and the Maiden couldn’t have been better suited for the Roman Polanski treatment if Polanski had written it himself. Starring Sigourney Weaver as Paulina Escobar, a woman whose haunting memories of imprisonment and rape are reawakened when her husband (Stuart Wilson) brings home a man she believes tortured her (Ben Kingsley), Maiden united one of Polanski’s strongest casts with some of his most familiar themes. Though it wasn’t one of his biggest financial successes, it signaled a critical return to form after the comparative disappointment of 1992’s Bitter Moon; Marc Savlov of the Austin Chronicle was one of the writers who offered praise, calling Death and the Maiden “a streamlined razor-ride of a movie: taut, riveting, and a psychological horror show that will leave nail-marks in your palms for days afterwards.”

8.

Nobody plays an adorable nerd with unsuspected emotional depth quite like Ed Helms — which made him the ideal leading man for 2011’s Cedar Rapids, a tender comedy about a naive insurance agent who’s called into duty at the last minute when he’s asked to head out to the “big city” and represent his company at the all-important regional convention. As Helms’ girlfriend back home, Weaver didn’t get to join in any of the memorable, John C. Reilly-assisted debauchery that follows, but their relationship helped add poignant overtones to a film that Tom Long of the Detroit News described by saying, “Considering it has to do with infidelity, bribery, drugs, drinking, loutish behavior, fraud and prostitution, Cedar Rapids is really kind of a sweet movie.”

7.

Starring Mel Gibson as a journalist whose hunger for a big story leads him into the heart of an Indonesian coup — and earns him a busted eye in the process — 1983’s The Year of Living Dangerously reunited Gibson with his Gallipoli director Peter Weir, earned Linda Hunt an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress (and for good reason: She played a half-Chinese dwarf named Billy Kwan), and gave Weaver the chance to have some high-stakes romance in an impeccably crafted war drama inspired by true events. “The Year of Living Dangerously is a flawed film,” wrote Dan Jardine of the Apollo Guide, “but it is richly textured and imbued with enough emotional and intellectual subtlety to make it a rewarding experience.”

6.

It isn’t especially well-remembered today, despite a terrific cast that includes Morgan Freeman as a police lieutenant embroiled in a murder case that’s also being investigated by a TV reporter (Sigourney Weaver) and a janitor (William Hurt), but with that killer cast and a bit of expert late-period direction from Bullitt director Peter Yates, 1981’s Eyewitness is the sort of perfectly serviceable cat-and-mouse mystery thriller that’ll help you pass a painless 103 minutes on your next lazy Saturday afternoon. “Every scene develops characters,” mused Roger Ebert. “And they’re developed in such offbeat fidelity to the way people do behave that we get all the more involved in the mystery, just because, for once, we halfway believe it could really be happening.”

5.

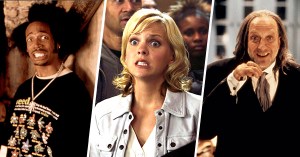

Sporting a blonde wig alongside Tim Allen and a heavily made-up Alan Rickman, Weaver helped parody the conventions of the sci-fi genre — as well as, you know, sci-fi conventions — in 1999’s Galaxy Quest, which sends the washed-up cast of a long-canceled TV show on a real-life space adventure. Funny and affectionate, Quest scored a $90 million box office hit while also earning accolades from critics like Film Threat’s Chris Gore, who called it “A hilarious spoof of Trek and Trek fandom” before pointing out, “While Galaxy Quest could have easily taken potshots at geeks, rather the film acts as more of a celebration of these sometimes misguided devotees.”

4.

Dave is nothing if not laughably unrealistic — a temp agency owner (Kevin Kline) stands in for the President, hires an accountant to fix the federal budget, and dreams up a jobs bill that will provide work for anyone who wants it, making the First Lady (Weaver) fall for him along the way — but even in the go-go 1990s, it appealed to our best and brightest hopes for our elected leaders, and in today’s vituperative political climate, it’s more of a funny, warm ‘n’ cuddly fable than ever. Janet Maslin of the New York Times was certainly charmed during its original release, admitting that “In spite of this sogginess, and despite a self-congratulatory, do-gooder streak that the film discovers within Dave, this comedy remains bright and buoyant much of the way through.”

3.

No film makes it to the screen as it’s originally envisioned by its writers, but Ghostbusters took a particularly circuitous journey: Originally, Dan Aykroyd planned to assemble it as a project for himself and John Belushi, with all sorts of big-budget shenanigans, and supporting roles for Eddie Murphy and John Candy. It was only after a ground-up rewrite by Aykroyd and Harold Ramis that Ghostbusters became the box office behemoth it was destined to be, racking up an an astounding $238 million tally throughout 1984 and 1985 — and a brilliant ensemble comedy offering memorable characters and quotable lines to a cast that included Bill Murray, Ernie Hudson, Rick Moranis, and (of course) Weaver as Dana Barrett, the concert cellist whose refrigerator happens to be a demonic gateway. Shrugged the Guardian’s Andrew Pulver, “What’s not to like?”

2.

Weaver’s first leading role in a film turned out to be the one that would stick with her for decades: Ellen Ripley, the astronaut whose close-quarters encounter with a frighteningly smart (and lethal) space creature presages a centuries-long war for the fate of the human race. But as deliberately as it teased at the edges of a broader mythology, Alien also worked as a gripping, gleefully inventive standalone sci-fi action thriller. Calling it “A haunted-house movie set in space,” Salon’s Andrew O’Hehir wrote that it “also has a profoundly existentialist undertow that makes it feel like a film noir — the other genre to feature a slithery, sexualized monster as its classic villain.”

1.

It seems absurd now, but for a time, execs at 20th Century Fox weren’t interested in a sequel to Ridley Scott’s Alien — they didn’t think it had been profitable enough to justify a second chapter — and even after James Cameron’s persistence earned Aliens a green light, a pay dispute between Sigourney Weaver and the studio almost threw the whole thing off the rails. And even after it officially got started, the production had more than its share of bumps in the road; everything from on-set strife to the sequel’s tonal shift (“more terror, less horror,” to paraphrase Cameron) had the potential to render Aliens just another unnecessary sequel. The end result, of course, was quite the opposite: Ripley’s action-packed return captivated audiences, dominating the box office for a solid month, and earned a near perfect score from critics, who showered it with praise as both a terrific follow-up (Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader said it “surpasses the original,” while Combustible Celluloid’s Jeffrey M. Anderson called it “everything a sequel should be”) and a solid chunk of sci-fi in its own right (Empire Magazine’s Ian Nathan declared it “truly great cinema”).