TAGGED AS: archives, Black History Month, movies, reviews, rt archives

Within Our Gates. (Photo by Courtesy the Everett Collection)

We live in a time where some of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood are African American, and some of the most impactful films in theaters and on streaming – as well as the most profitable – are directed by African Americans. It’s the same story in music, pop culture, on YouTube and TikTok, and beyond: In today’s media landscape, the influence of Black creators and of the Black perspective is outsized.

It wasn’t always that way, especially in film. Going back in time, there was generally a deep segregation in the industry – one could argue there still is, but that’s another story – that was reflected on the screen from the earliest days of American cinema. With Black creators largely relegated to the sidelines, and Black performers largely forced to conform to, and thus reinforce, stereotypes in major Hollywood films throughout the 20th century, true representation of Black lives in the country was absent from the screen. But one group of filmmakers pushed back, founding a genre of films made by and for African Americans right back to the medium’s infancy, combating stereotypes and setting the tone for an independent Black cinema right through to today. This genre is called “race films.”

Body and Soul. (Photo by Courtesy the Everett Collection)

What are “race films”? First, a bit on the history from which they emerged. In the deeply troubled history of American cinema, there has always been a tension between who could play what on screen. For African Americans, the legacy of the “minstrel shows” that had set the groundwork for Black representation in much of American popular culture in the late 19th century would set the stage for how African Americans could and would be portrayed on screen when the technology of the movies came along. Consider one of our earliest cinematic works, 1913’s Edison’s Minstrels, which featured whites in Black face and which is generally considered one of the first films to match sound with a minstrel show. (You can read contemporaneous reviews of Edison’s display below.)

The long tradition of segregation – a.k.a. Jim Crow, a.k.a. “the color line” – further defined what roles African Americans could play on screen for a large part of the century; Hollywood usually cast us as singers or dancers, or as maids, butlers, porters, and other servants. (So much have these representations echoed, even to today, that filmmakers like Spike Lee [with Bamboozled], Jordan Peele [with Get Out], and Ryan Coogler [with Black Panther] continue to resist and hit back at these early stereotypes.)

(Photo by Courtesy the Everett Collection)

The long shadow of the color line cut through all aspects of movies: not just in typecasting, but in segregated theaters and, of course, the absence of people of color behind the lens. Under the harsh divisions of the color line, the thriving but limited African American cinema suffered – between the late 1940s and 1969, there were almost no movies directed by African Americans released commercially. It’s a pretty shocking fact, but all too consistent with the de facto segregation that limited opportunities.

Race films developed alongside and in reaction to this industry that pigeonholed African Americans or shut them out completely, and date back to as early as 1920 and the works of legendary African American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. In a way – and heart on one hand, here – they were a straight-jacket approach to creating Black art that mirrored the segregation of the times, having to generally be produced outside of the Hollywood system. They featured actors who were of African heritage, and the films were significant for showcasing how talented actors could do more than play the stereotyped roles offered to them in major studio releases. And they were produced by independent production companies and focused on the everyday life of what it meant to be Black in America.

The Scar of Shame. (Photo by Courtesy the Everett Collection)

While the system was a product and mirror of segregation, it also fostered an entire generation of independent African American filmmakers and helped establish a “Black cinema” in America, an artform and system where Black directors were empowered to be independent – raising money, shooting and editing, and scoring films themselves. These movies gave African American audiences and actors a forum to articulate their own identity outside of the studio system which rarely bothered with the full spectrum of that identity.

Among the most influential players in race films were white-owned film production groups like Reol Productions/Norman Studios, which propelled Edna Morton, one of the first major African American screen sirens, to stardom, as well as the highly regarded studios of African American filmmakers Micheaux (Micheaux Film and Book Company), and Spencer Williams of Amos ’n’ Andy fame, whose Amegro Films produced the classic 1941 race film, The Blood of Jesus.

There are so many films today that show us the complexities of contemporary African American life, from Julie Dash’s poetic Daughters of the Dust and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, to the work of Tyler Perry and on to Ava DuVernay’s films and those from her production company, Array, and beyond. But it’s always good to know that as great as things are now – or at least, as much as they are improving – we should never lose track of where things used to be and the pioneers who worked to create their art within those constraints.

As always in American cinema: It’s complicated.

DJ Spooky, a.k.a. Paul D. Miller, is a composer, multimedia artist, and writer whose work immerses audiences in a blend of genres, global culture, and environmental and social issues. He is the Executive Producer of Pioneers of African American Cinema, a collection of the earliest films made by African American directors, which was released on DVD in 2015.

As part of the RT Archives Project, Miller chose the below films to help give readers a historical perspective on race films. The Rotten Tomatoes team sourced (mostly) contemporaneous reviews for each, so you can read what critics and writers had to say about them at the time of their release. Where possible, we have highlighted the reviews of Black film critics.

Within Our Gates (1920)

![]() 100%

100%

In this early silent film from pioneering director Oscar Micheaux, kindly Sylvia Landry (Flo Clements) takes a fundraising trip to Boston in hopes of collecting $5,000 to keep a Southern school for impoverished Black children open to the public. She then meets the warmhearted Dr. Vivian (William Smith), who falls in love with Sylvia and travels with her back to the South. There, Dr. Vivian learns about Sylvia’s shocking, tragic past and realizes that racism has changed her life forever.

“Micheaux’s narrative manner is as daring as his subject matter, with bold flashbacks and interpolations amplifying the story.” – Richard Brody, The New Yorker, February 2016

Body and Soul (1925)

![]() 86%

86%

Another film written, directed, and distributed Micheaux, Body and Soul features icon Paul Robeson in dual roles: one as a criminal pretending to be a minister, and also his twin brother.

“Body and Soul is a picture of great emotional appeal, indeed… The picture was well acted, especially the part of the minister, which was played by Paul Robeson.” – Maybelle Chew, Baltimore Afro-American, Sept. 11, 1926

Scar of Shame (1927)

![]() 100%

100%

In this silent film produced by the Philadelphia-based Colored Players Film Corporation – which made silent melodramas with African American casts – a young man’s reluctance to introduce his working-class bride to his bourgeois family leads to tragedy.

“The Scar of Shame is a classic [film] presenting a picture of a cultural element of the race which is seldom portrayed on the stage or screen.”– The Pittsburgh Courier, April 27, 1929

Imitation of Life (1934)

![]() 88%

88%

Widow Bea Pullman (Claudette Colbert) and her daughter, Jessie, take in a fair-skinned black girl and her mother, housekeeper Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers). Struggling to make ends meet, Delilah shares her family pancake recipe with Bea, and the two decide to start a business on the Atlantic City boardwalk. Together, the women find great success and considerable fortune, but they also encounter family hardships and some deep-seated identity and racial problems. The film – which dealt with themes like passing and racial justice – was nominated for three Academy Awards.

“You feel some of the weight of the bars of race prejudice in this country when you see, probably for the first time, the true symbol of the American Negro struggling against these bars as Fredi Washington portrays the role of Peola.” – Fay M. Jackson, Pittsburgh Courier, Dec. 15, 1934

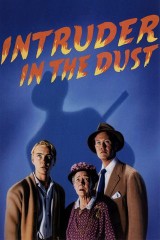

Intruder in the Dust (1949)

![]() 93%

93%

In Intruder in the Dust, Lucas Beauchamp (Juano Hernandez) is a strong, proud African-American man accused of murder in small-town Mississippi in the 1940s. As the town’s white residents prepare to lynch him, a teenage boy named Chick (Claude Jarman Jr.), whom Beauchamp had once saved from drowning, becomes convinced of the man’s innocence, and races to discover the real murderer before it’s too late. This film, adapted from William Faulkner’s 1948 novel, was made on location in his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi.

“The power of Intruder in the Dust stays with an audience far after the end of the movie… Intruder smashes in a straight, uncompromising direction at those who contain a little bit, a bigger amount or a great deal of intolerance.”” – Robert Ellis, California Eagle, Nov. 17, 1949

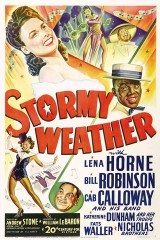

Stormy Weather (1943)

![]() 95%

95%

This star-studded 20th Century Fox film was one of two big-studio musicals with African American casts released in 1945. (The other was MGM’s Cabin in the Sky.) In Stormy Weather, Bill Williamson (Bill Robinson), a struggling performer, meets a beautiful vocalist named Selina Rogers (Lena Horne). Bill promises her that they will be together after he becomes a success. However, he and Selina both skyrocket to fame and lose contact. Fortunately, Bill just might get one more chance to woo Selina at a huge musical stage show. Popular entertainers of the 1940s, including Fats Waller and Cab Calloway, perform as themselves in the film.

“Without a doubt Stormy Weather surpasses all other all-colored pictures this writer has ever seen. The acting, costumes, and scenery are superb.” – Evelena D. Jackson, Baltimore Afro American, July 31, 1943

Black and Tan (1929)

Set during the Harlem Renaissance, musical short Black and Tan was the legendary Duke Ellington’s first screen appearance as well as the debut of actress Fredi Washington – she would go on to become one of the movies’ first African American stars and a Civil Rights activist.

“The all-dialog short has some excellent fancy photography as the second attraction, with the music the first, and the Harlem cafe life for the rest.” – Sime Silverman, Variety, Nov. 6, 1929

The Edison Minstrels (1913)

![]() 67%

67%

Not an example of a race film, but of the thread of racial stereotypes that traces right to the beginning of cinema, this series of mostly comic set-pieces was played in the early 20th century on Thomas Edison’s invention, the kinetophone, which synchronized recorded sound with moving pictures from the kinetoscope. The short sets featured white actors in blackface.

“The pictures are a genuine success and bid fair to revolutionize the moving picture game. They are wonderfully lifelike; the voice and the mannerisms are so naturally reproduced that it is difficult not to believe that the figures shown on the screen are not human beings.” – Kelcey Allen, New York Clipper, Feb. 22, 1913

Additional research by Tim Ryan