This weekend, the movie everyone’s talking about is Suicide Squad — and while a number of cast members have earned critical applause for their efforts, it’s Jared Leto‘s turn as the Joker that we’ve all been waiting to see. In honor of that moment’s eagerly anticipated arrival, we’re dedicating this week’s feature to a fond look back at some of the brightest critical highlights from the Oscar-winning star’s career, and the results add up to one admirably eclectic journey. It’s time for Total Recall!

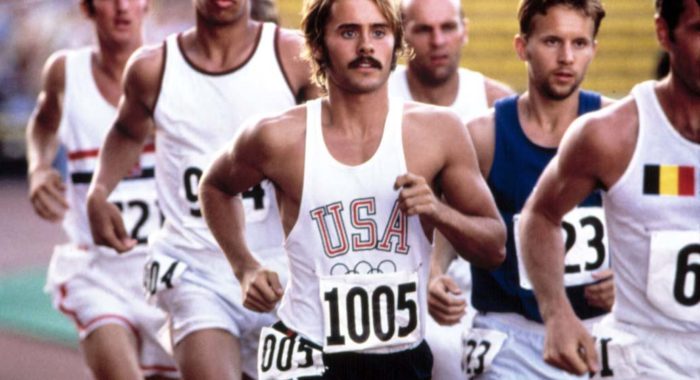

Leto was still Jordan Catalano from My So-Called Life in a lot of filmgoers’ eyes when he scored the leading role in Prefontaine — but those who passed on director Steve James‘ biopic about the titular Olympic runner missed the opportunity to see the results of Leto’s Method dedication for the first time on the big screen. As he would with subsequent roles, Leto dove in completely, adopting Prefontaine’s voice and running style; the end result, coupled with an already-eerie physical similarity, went a long way toward proving he was more than just a pretty face. Alas, the rest of the movie didn’t quite live up to Leto’s efforts, and many critics dismissed Prefontaine as a TV-worthy hagiography — but it did have its fans, including Roger Ebert, who wrote, “Here is a sports movie in the tradition of the best sportswriting, where athletes are portrayed warts and all. You do not have to be nice to win races, but you have to be good.”

Fresh off My So-Called Life, Leto got his big-screen break with a supporting part in director Jocelyn Moorhouse‘s adaptation of the Whitney Otto novel How to Make an American Quilt. Starring Winona Ryder (with whom Leto would later share screen time in Girl, Interrupted), the movie offers an episodic look at the stories of a group of women who seek to soothe the nerves of a bride-to-be by sharing some hard-won wisdom from their own pasts. Leto’s role, as the hunky kid who engages in an interracial affair with his family’s servant, takes up a relatively brief portion of the movie — but it got him started at the movies, and played a part in a modest critical and commercial hit that, as the New York Times’ Caryn James wrote, “takes the makings of a limp ‘women’s weeper’ and as if by magic, spins them into gold.”

How many chances does a guy get in life to play one half of a pair of arms-dealing brothers opposite Nicolas Cage? Leto got his opportunity with Lord of War, writer-director Andrew Niccol‘s 2005 war crime drama about a couple of crazy kids with a dream to make a bunch of money by selling lethal weapons to anyone with enough money to make the sale. The end result of years of research on Niccol’s part, it seethes with righteous anger without tipping over into didacticism — and offers Cage and Leto plenty of material to sink their dramatic teeth into, including an arc for Leto’s character that includes drug addiction in addition to morally reprehensible gun-running. “Niccol is no stranger to hot-button issues,” wrote Time Out’s Dave Calhoun, “but he outdoes his previous efforts by injecting this satire of war profiteering in the Halliburton age with a wicked arsenic wit.”

Leto’s fondness for projects lying off the beaten path was further reflected in Mr. Nobody, writer-director Jaco Van Dormael‘s sci-fi drama about a 118-year-old man whose memories send him back to three critical junctures in his long life — and send the viewer wandering along alternate timelines that might have resulted from different decisions along the way. The movie bowed in Venice in 2009 and didn’t make it to the States for another four years, the kind of delay that often suggests more than a few fundamental flaws in a film — yet while it wasn’t exactly rapturously received by critics, reviews outlined a picture whose charms outweighed its circular, meandering narrative. “Never mind that several characters seem to gain or lose British accents throughout the course of the film,” wrote the Washington Post’s Michael O’Sullivan. “The lack of continuity only enhances the sense of deliciously dizzying disequilibrium.”

It took nine years, but Bret Easton Ellis’ controversial 1991 novel got the big-screen treatment with this adaptation, which cast Christian Bale as the loathsome, status-obsessed serial killer Patrick Bateman, Reese Witherspoon as his equally shallow girlfriend, and Leto as a smarmy co-worker whose superior business card sets off the movie’s killing spree. Though many of the cultural touchstones described in the book had faded by the time American Psycho reached the screen, its central observations — and the consumer culture that produced them — remained as timely as ever. Its torrent of generally unappealing behavior and horrific violence make Psycho an unpleasant film, but one that, in the words of Time’s Richard Corliss, “needs to be seen and appreciated, like a serpent in a glass cage.”

A claustrophobic thriller with the heart of a B movie, Panic Room found director David Fincher wielding a stellar cast (including Jodie Foster, Forest Whitaker, and a young Kristen Stewart) and dropping them in the middle of a tightly wound, tension-filled storyline. Panic sets in almost immediately, with single parent Meg Altman (Foster) and her daughter Sarah (Stewart) spending their first night in the huge Manhattan brownstone Meg has just purchased; what Meg and Sarah don’t know is that their new home contains some very valuable hidden treasure — as well as a trio of very bad men (including the skin-crawling Dwight Yoakam and a mysteriously cornrowed Leto) who will stop at nothing to steal it. Ultimately, Panic Room is mostly just a nail-biter — albeit one assembled with uncommon flair. “This is just a big, dumb, commercial suspenser,” admitted Empire’s Caroline Westbrook, “but it’s one of the best for ages, reminding us that it is still possible to make a high-quality piece of popcorn entertainment.”

Marking director Terrence Malick’s return from a 20-year absence and featuring the work of a stellar ensemble cast that included Leto, Woody Harrelson, Adrien Brody, George Clooney, John Cusack, and Sean Penn, The Thin Red Line was the film buff event of 1998. Even with a 170-minute running time, there wasn’t enough Line to go around — in fact, during all the whittling between its five-hour first cut and the theatrical version, Malick excised entire performances by Martin Sheen, Gary Oldman, Billy Bob Thornton, Viggo Mortensen and others, meaning that even if Leto’s performance as Second Lieutenant Floyd Whyte isn’t his biggest role, it’s really saying something that it ended up in the movie at all. And for most critics, there was no arguing with the end result; as Norman Green wrote for Film.com, “It wrestles with complexity, speaks to us in poetry, weaves multiple narrative strands into a tapestry, opens the festering wounds of war and gazes inside without blinking.”

Like the Hubert Selby, Jr. novel from which it’s adapted, Darren Aronofsky‘s Requiem for a Dream is certainly not for everyone. An unflinching look at the misery of addiction, Requiem follows the hellish descents of a widow named Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn), her son Harry (Jared Leto), his girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly), and Harry’s friend Tyrone (Marlon Wayans). After 102 minutes, all four characters have been pretty well run through the wringer; Burstyn winds up institutionalized, Leto loses an arm, Wayans has to go cold turkey in a jail cell — and Connelly crosses paths with Big Tim, played with thoroughly skeevy elan by Keith David. Good taste prevents us from getting into the exact nature of their relationship; suffice it to say that Connelly’s character arc demonstrates that some people will do just about anything to get their fix, and David’s performance reminds us that other people will stoop at nothing to take advantage of an addict. “Never have we been taken this close to the edge, and never have the characters teetering over it elicited so much sympathy,” wrote Eugene Novikov of Film Blather. ” Requiem is difficult to watch, but it richly rewards those who stay with it.”

Yes, we are going to talk about Fight Club. Initially rejected by critics and ignored by audiences, director David Fincher’s third feature steadily built a cult following on DVD; these days, it’s widely regarded as one of the best films of the ‘90s, which not only helped reaffirm Fincher as a director of stylishly thoughtful fare, but established the Hollywood bona fides of author Chuck Palahniuk, from whose novel the movie was adapted. The plot follows the eager descent of a nameless protagonist (Edward Norton) into the anti-establishment crusade of Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), who organizes the titular underground brawling network whose participants include the ill-fated Angel Face (Leto). On a deeper level, the story functions as a bloody, black-humored indictment of consumer culture, but more importantly, in the words of ReelView’s James Berardinelli, “Fight Club is a memorable and superior motion picture — a rare movie that does not abandon insight in its quest to jolt the viewer.”

Nothing screams “for your consideration” like an actor physically transforming himself for a role, to the point that it’s become something of a signal for filmgoers cynical enough to be suspicious of a star’s motivations when taking a part. But as often as not, that commitment pays off; just ask Jared Leto, whose rather frightening pre-shooting regimen included dropping more than 40 pounds to portray Rayon, the transgender HIV-positive woman whose story lends a poignant anchor to Jean-Marc Vallée‘s fact-based Dallas Buyers Club. Academy voters ultimately honored the movie with six nominations — three of which it won, including Best Actor for Matthew McConaughey and Best Supporting Actor for Leto. “Dallas Buyers Club represents the best of what independent film on a limited budget can achieve,” wrote Rex Reed for the New York Observer. “Powerful, enlightening and not to be missed.”