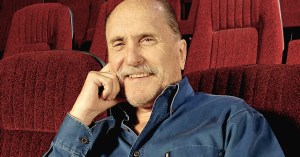

Interview: Picking Up on William Friedkin’s Cruising

The director on his newly re-mastered 1980 film.

William Friedkin will forever be remembered as one of the legendary New Hollywood directors of the 1970s. He and the “film brats” worked feverishly during a decade-long confluence of bewildered (but rich) studio executives who entrusted young (but learned) filmmakers to win back disaffected (but daring) audiences by filming innovative and accessible stories. Friedkin and his band of precocious auteurs loved movies more than anything and only when their egos and wallets grew larger than their desire to continue the cinematic innovation of the European New Waves did it all come crashing down.

Friedkin’s best known and most-celebrated work is The French Connection (for which he won a Best Director Oscar at the age of 26), which he followed with the ever-controversial The Exorcist. Outside of dedicated cinephiles, most would be hard-pressed to name his other films. However, Friedkin continues to work even today (see this year’s psycho-thriller Bug), creating movies that, while not as groundbreaking as his earlier work, share a strong thematic consistency and show the artist to be as keen and original as he ever was, if in smaller ways.

RT met with the notorious director — who’s been featured with the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, and Martin Scorsese in Peter Biskind‘s unforgiving tome on 1970s cinema, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls — to discuss his 1980 film Cruising, which will get the deluxe DVD treatment from Warner Home Video on September 18. Cruising stars Al Pacino as Steve Burns, an undercover cop who must infiltrate the gay New York City underworld to attract a serial killer whose modus operandi is to pick up young men in S&M bars. Armed only with the information that the murderer targets men of his type (but not certain if the victims are even related, or whether there are multiple killers), Pacino must shed his inhibitions and adopt a homosexual persona until he himself gets “cruised.” When the film opened, liberal culture in America was ending just as the gay rights movement got underway. Cruising portrays a paranoid era when personal identity had suddenly become a dangerous secret.

You’ve always been an unflinching director, both with the subject matter you choose and how you treat those subjects onscreen — there’s a sense of immediacy and rawness. Cruising follows your other work in that sense. Is that what attracted you to the story? How S&M was a subterranean culture that you could explore in a way both shocking and revealing?

William Friedkin: I think that’s probably a good way to put it. I never thought of it as anything shocking at the time. I thought it was fascinating. There are many outside events that led to making Cruising but what drew me toward it more than anything was that it was based on an actual series of murders that took place in Manhattan around that time, and they were unsolved. I was making a film about unsolved murders. That was really the unusual and unique thing about it.

Because at that time, and even more so today, a movie about a murder starts and it’s two hours long, at the end of two hours the murder is solved and everything gets put back neatly into its drawer. This convention is nowhere worse than on television. At nine o’clock somebody gets murdered and at 10 o’clock the murder is completely solved and put away. I realized because of a lot of contact that I had with police officers all over the country and many parts of the world that’s not how it works. There are many more unsolved murders than solved. There is this evil out in the world that’s vying with good on a constant basis. The thing that attracts me to almost every film I’ve made is the thin line between good and evil. In all the characters there are no real, single villains or heroes. There’s a part of good and [a part of] evil in all the characters, which is what I really believe. So this was a way of making a film about unsolved murders. And at the time, that had not been done. I don’t know if it’s been done since. But it was considered, if not confusing to audiences, then ambiguous. And it may to some extent still be, because audiences are conditioned to know who the killer is. When a normal movie’s over, you walk out saying, “I knew it was that guy all the time!” But Cruising isn’t “that guy.” And that’s what happened in the series of murders that took place, which prompted me to do the film. They weren’t solved.

In that sense, the story has connection to San Francisco through a comparison to the Zodiac murders; the sense of everyman killers — your neighbor could be a murderer — that sense of paranoia.

WF: Those were unsolved. And the BTK [bind, torture, kill] murders in Kansas City [between 1974 and 1991]. They got the guy 30-some years later.

Is that why you always resist resolution at the end of your movies?

WF: There is no resolution. I don’t resist it. Cruising is a film about a series of murders that took place to which there were no clear answers. They pretty much knew who did one or a couple of the murders, but not all of them. Nor is it suggested that the murder was gay. One or two of the murderers may have been gay. They may also have been seeking vengeance against gay people. There was a lot of that going on at the time. Even in recent years where young people are victimized because of their religion or sexual preference or something else. It’s pretty frightening that’s still occurring.

WF: Cruising definitely reflected the attitude of the times: The temper of the times. How the culture was either accepted or ignored, at that particular time, and then attention would be brought on it because of this or that event, like the murders. But what was happening during the time we were making the film, there were all of these gay people dying and it wasn’t clear why. There was a “gay disease”. And it was the beginning of AIDS, but those were considered unsolved deaths at the time. Shortly after, maybe by the mid-1980s, the largest group of AIDS victims was women in prison. Then they were able to trace it to needles, and the exchange of needles, either for transfusions or drugs. But at first it was thought to be a plague that struck only gay people. And so, again, it was a series of unsolved murders. Unsolved killings: Why, all of a sudden? I had many friends who were contracting AIDS, and many of them were not outwardly gay. It’s hard to underestimate how paranoid people became with the onset of AIDS.

The sense of suspicion comes through in the movie. And in the middle of it, you interject this character of Steve Burns (Al Pacino). You put this guy in the middle of all these shifting identities, hidden identities that conceal potential danger, and his own identity starts to shift. He starts to question his own sexual orientation. Could you talk about how you found that character with Pacino?

WF: Steve Burns is based on a guy who went through that; a police officer named Randy Jurgensen. He [Jurgensen] plays a detective in the movie, in the morgue scene and in the interrogations. He was also in The French Connection. He had a 20-year career as a New York City detective. He was involved in the periphery of the actual French Connection case, and the murders in the Harlem mosque, and he had a number of extraordinary cases. He was sent into the leather bars, which were at that time subterranean, because there was a series of killings where the victims all had a similar appearance, and they looked like Randy; about his height, dark hair, mustache, swarthy complexion. The police had no clues and basically threw up their hands.

Randy was sent in to try and attract the killer. These were his experiences, much more so than anything that’s in Gerald Walker’s book, Cruising. I used the basic foundation from that book, but his book is not set in the leather bars. Randy’s life was. He went through that. He told me how he became disoriented and confused as a result of that experience. Because you’re dealing with basic human needs, sexual and emotional, quite apart from whatever sort of religious or moral or social or ethical rules we’re given, you’re dealing with life at its most primitive level. Randy was in there to do the job of a police officer, and he had no idea what in the hell he should be doing. But he was being held out there as bait for a killer. So it was Randy’s very vivid descriptions of his life during this period that formed the basis of Cruising.

The description of the killer that Burns was given is equivalent to the modern “black male between 18 and 30, between 5’5” and 6’5””, which is so general it’s practically useless. So he does have to put himself out there; he has to be very open, but suspicious at the same time.

WF: It’s fear. He wasn’t allowed to carry a gun. He was afraid. As with all undercover police work, you’re asked to be an actor: A convincing actor. A handful of them were [convincing actors], and those were the guys we made movies about. Most of the undercover detectives cracked under the tension or emotion distress of being thought of for 20 years as part of this or that Mafia outfit. Most of that went very badly for the guys who did it, because they weren’t actors.

To succeed, you have to give yourself over to the farce so completely that you’re at risk of truly becoming the role.

WF: Yes, exactly. Of course, the very best cops are the ones who think like criminals anyway, who could have gone either way.

That theme of play-acting as a policeman is made explicit in the ironic scene when Pacino shows up to “Precinct Night” at the local leather bar, and he’s the only one who’s not dressed as a cop, so he gets kicked out, even though he’s the only one there who’s actually a cop.

WF: There was “Precinct Night” where everyone had to dress up as a cop. And it was interesting because the bars in New York were owned at that time by two groups: the Mafia and cops. Sometimes working cops, but sometimes ex-cops who made so much money that they retired. The police that were supposedly out there for protection were actually owners of the clubs where these crimes were originating.

WF: Not the way it was. I mean, I don’t want to say this in a way that can be construed as sour grapes, but there are no giants at work in cinema today, or for any long period of time. Perhaps that will develop. But there are no Antonionis, no Fellinis, no Bergmans, no Truffauts, the guys who brought modern cinema into the category of art. That’s not happening today. Most of the popular films are remakes or sequels or teen-oriented comedies. But the people who work at these DVD divisions of major studios are big film buffs. Most of them are guys who were stuck in the 1970s and developed a great love for the history of film, both American and international. They represent the true cinematheque. That’s the real American cinematheque; the guys who run the DVD companies that bring back classic films, some of which had very small footprints in their day but were remembered as classics and would have no other way to be seen by subsequent generations were it not for DVD technology.

And I don’t mean VHS, because while the VHS did bring back a lot of great classic films, they didn’t look good. The process wasn’t that great; it’s more of a recording device than a restoration device. But DVDs also involve restoration. In a way its similar to how the great painting around the world look better than they ever did since they were first painted — because time takes its toll even on a Rembrandt or a Vermeer — and a restorative painter has to be someone not only of genuine talent by him or herself, but someone who can appreciate what the original artist intended. So the way we make these DVDs now is better and with more t.l.c. than they ever received as prints.

The DVD is basically a flawless process. I see these films on DVD that I first saw in theaters that look better than they ever looked in the theaters. You run a 35mm print through a projector and it picks up scratches immediately. On each subsequent run, there are more scratches, and tears, and re-splicings. I saw four films by Antonioni recently on DVD, and I remember them very well because I saw them over and over again in theaters, and the DVD is much better. It’s a fantastic way to see films. The print of Cruising for theaters is also done with digital remastering. We don’t have a 35mm print anymore. It doesn’t exist. The negative was so screwed up and the sound was out of sync. The guy who worked on it with me to restore it told me that the only negative he’s seen that was worse than Cruising was the negative for The Godfather. He said it was allowed to completely deteriorate. Because it was shot so dark, and 35mm fades after a while, that when a scene is dark it tends to go mushy as it deteriorates; the delineation between light and dark disappears and you have mush.

Do you think there’s a danger in almost — how to phrase this? — in Hollywood embalming itself in the DVD process; in enshrining its old classics and not concentrating on creating new classics?

WF: Well, if you feel that exhibition is “embalming.” I don’t. Do you feel that the paintings of Van Gogh are “embalmed” in museums? No. They’re there to be seen by subsequent generations. The first performance of Hamlet, which I think was in about 1601, with Richard Burbage playing Hamlet, if they had no other way to distribute that play it would have been seen then and then only. But along came the printing press, and the publication of Shakespeare’s plays, the first folio, which during his time did not exist. People couldn’t read Shakespeare’s plays when they were performed unless they were acting in them. And even in that time, the plays were changing from performance to performance and the actors were saying, “Wouldn’t it be better if I did this, or said this?”

Shakespeare’s plays were reconstructed by two guys named Heminge and Condell, who went around to the surviving actors of the Globe Theatre and asked them, “What did you say? What were your lines?” And these guys recalled their lines. That’s why there’s a lot of controversy about the authenticity of Shakespeare’s plays. At the very first performance of Hamlet— which was done to an audience at the Globe Theatre in Stratford where they had no chairs– they had to stand for four hours, and eat, and they used to talk back to the actors. When Richard Burbage played the death scene in Hamlet the audience screamed out, “Die again, Burbage! Die again!” He played the death scene three times at the first performance. Then they reproduced Shakespeare’s plays. Is that embalming them? No. It gave them a new life for subsequent generations. Each generation interprets these plays in their own way. Each generation will interpret Cruising in their own way, based on the mores that exist, and the progress that the gay community has made since then. This was a very provocative issue when it came out because gays were just emerging from the closet. There is no closet now, really. I mean, yes, there are people who don’t wish to announce their proclivities, but they don’t have to [stay silent], as people did then. At that time if you said you were gay you might get fired. If you were a movie star and it came out that you were gay and you were an action hero or a romantic lead, your career was over.

WF: It was that, indeed. And I remember that. It was around then, but now it’s gone. To find someone in the closet, or to find a communist, today you have to go to a museum. Cruising was released during the early stages of gay activism, and progress toward understanding, or at least accommodation. So it was viewed by a different audience. Now, to have Warner Brothers create a DVD that looks and sounds better than the original ever did, it’s a filmmaker’s dream. Someday some of the films that are very popular today will disappear completely off the radar and then come back perhaps when a new technology is invented, and a new generation will be able to see and appreciate them. I applaud this technology. It has saved the legacy of international cinema.

In Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls he quotes you as saying, “The thing that drove me and still keeps me going is Citizen Kane. I hope to one day make a film to rank with that. I haven’t yet.” So, do you have a Citizen Kane in pre-production?

WF: No. No, that’s unattainable. I haven’t read Peter Biskind’s book, I know about it. It’s made up largely of facts, lies and rumors, as near as I can tell. What he chose to do more than interview the subjects themselves was to talk with ex-girlfriends, ex-wives, whatever. In any case, I probably said that, and I meant that. Citizen Kane is the film that inspires me. It’s like a composer saying, “I hope to one day write a symphony that rival’s Beethoven’s Fifth.” It’s impossible. It’s just not possible to do that anymore. It becomes a watermark. It’s because of those kinds of symphonies that symphonies continue to be written. It’s because of films like Citizen Kane, or the paintings of Rembrandt or Vermeer, that people are continually inspired to create. There are only two responses if you’re a filmmaker and you see Citizen Kane: One is, ‘that’s how I’m going to measure my work,’ the other is, ‘I quit.’ That’s it. Imagine looking at a Rembrandt portrait and you want to be a portrait painter. What’re you gonna do?

Take up photography.

WF: Take up photography, or give up, or commit suicide. And that’s true of all the iconic works of art: They’re to be aspired to. Unlike baseball’s home run record, they will never be exceeded. There will be others that may join them in the pantheon of great works, perhaps, but they will never be exceeded.

Hopefully through DVDs Citizen Kane will not be forgotten and will continue to influence directors.

WF: Hopefully, yes. Now, Citizen Kane is very much of its time. It influenced everything that came after. It was like a quarry for filmmakers. Like Joyce’s Ulysses or Proust’s In Search of Lost Time are quarries for writers. It’s all there. In Citizen Kane the very finest screenplay, acting, lighting, editing, cinematography, music, it’s all at its highest level in that one film. It’s all together. Maybe some day that’ll come together in an American presidency. We’ll have another president like Lincoln or Roosevelt.

Do you think that’s possible with modern media culture?

WF: You live and hope.

The deluxe collector’s edition DVD of Cruising is out next Tuesday, September 18.