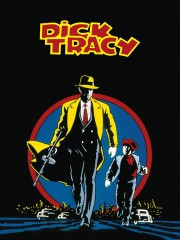

Hear Us Out: Dick Tracy Deserves More Love in the Comic Book Movie Canon

30 years after its release, Warren Beatty's star-studded, lovingly faithful comic adaptation is still one of the most unique examples of its genre.

(Photo by Buena Vista Pictures)

In the summer of 1989, Tim Burton’s Batman took the box office by surprise, decades before movies based on comic books could be counted on to draw in the crowds. Hot on his heels the following summer came another movie based on a famous comic character, this one from the funny pages of the Tribune Company’s syndicate, Dick Tracy.

The 1990 adaptation of Chester Gould’s yellow hat-and-coat-wearing detective finds a man too over-committed to his endless quest to put the City’s big bad mob boss Alphonse “Big Boy” Caprice (Al Pacino) out-of-business. It’s a full-time job that leaves Tracy’s girlfriend Tess Trueheart (Glenne Headly) feeling left out and worried about their future together. But their lives take a turn when Tracy rescues a wisecracking street kid (Charlie Korsmo) who wants to stay with the couple, a smooth-talking femme fatale named Breathless Mahoney (Madonna) enters the picture, and Big Boy escalates his turf war to wipe out Tracy. It’s a colorful fantasy world frozen in the early 1930s in a place where the good guys wear badges and the bad guys are noticeably grotesque figures with names like Pruneface, Flattop, and Mumbles.

Although Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy didn’t quite win over audiences and critics as strongly as Batman did the previous year, here’s why it remains a movie worth revisiting 30 years later for its wild direction, astonishing production design, and catchy music.

WARREN BEATTY’S DEDICATION TO THE SOURCE MATERIAL IS CLEARLY EVIDENT

(Photo by (c)Touchstone courtesy Everett Collection)

Part of the appeal of 1990’s Dick Tracy is that it doesn’t remotely resemble reality. Beatty, a fan of the Dick Tracy comic strips from back in the day, chose to stick to the source’s two-dimensional layout, limited color palette, and cartoon-esque aesthetics. According to Vox, the actor turned director and producer had first tried to adapt Dick Tracy for the screen back in the 1970s. A number of notable directors were considered for the project, including Steven Spielberg, John Landis, Walter Hill, and Martin Scorsese, but ultimately, Beatty gave himself the job.

Introduced in 1931 at the tail-end of Prohibition, Dick Tracy quickly became a popular comic strip crimefighter who battled scary-looking mob bosses and shifty gangsters. Before Beatty’s movie, Dick Tracy enjoyed a brief run as the hero of serials and movies in the 1930s and 40s, as well as occasional TV appearances in the 1950s and 60s. Many of these adaptations jettisoned the character’s original backstory and supporting players, but Beatty wanted to do justice to his first big-budget adaptation.

For Beatty, that meant going all-in on Tracy’s original aesthetic, which mostly took its cues from how newspapers cheaply printed its comic pages; there would be limited colors and patterns on

Milena Canonero’s costumes. While Beatty already came to the starring role with his character’s square jaw, make-up artists John Caglione Jr. and Doug Drexler would create the monstrous features of the mobsters. The screenplay by writing duo Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr. (Top Gun, The Secret of My Success) includes many characters from the original comic strip series like Tess, the orphan who names himself after Dick Tracy, and the rogues’ gallery. Although the film didn’t become a roaring success at the box office, it still made its parent distributor Disney over $100 million at the domestic box office, and it went on to earn seven Academy Away nominations –– including nods to Pacino, Canonero, and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro –– and win three Oscars for Best Makeup, Best Art Direction, and Best Original Song.

THE FILM’S EYE-POPPING PRODUCTION DESIGN IS A SIGHT TO BEHOLD

(Photo by Buena Vista Pictures)

There’s a good reason Dick Tracy took home the Oscar for Best Art Direction: It’s truly stunning what Beatty, production designer Richard Sylbert, and art director Rick Simpson accomplished on an astonishing scale. Before computer technology could easily and cheaply create worlds beyond our reality, filmmakers had to rely on old school practical effects to make these made-up worlds appear on screen. That meant tricking out a lot of backlot space to look less like our world and more like Tracy’s, carefully set-decorating each room to look as they would in a comic strip and using matte paintings and other visual effects to bring the inky pages of a newspaper to life.

Under the lens of cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, The Last Emperor), the colors of the sets and costumes brightly pop off the screen, much in the same way that comic strips in a newspaper would appear after pages of black-and-white text. The lighting in the movie sometimes casts a red or green glow over the wet pavement, and sometimes the shadows on Tracy’s face make him appear more like the hand-drawn character on the movie poster than Beatty. Vanity Fair noted how Storaro’s shooting style on the film helped create the illusion that this was a panel-by-panel Dick Tracy adventure. Through careful composition, his still camera would frame each moment as if it were a panel in the comic strip, taking the idea of a comic adaptation to a whole new level years before movies like 300 or Sin City did the same.

AL PACINO’S UNHINGED PERFORMANCE IS BOTH SURPRISINGLY INTENSE AND FUNNY

(Photo by Buena Vista Pictures)

As in the comic strips, Beatty’s Tracy is a pretty straightforward guy. He loves his girlfriend, he busts organized crime rings, and he’s unsure about settling down and adopting the orphan he rescued. That’s a bit of a meta-joke on Beatty’s longtime bachelor status, but it also works in the case of his workaholic detective. He doesn’t have the baggage of a lost home planet like Superman or the tragic death of his parents like Batman. He’s a straight man in need of a foil, a Joker to his Batman if you will.

In the movie, it’s up to Al Pacino as Tracy’s nemesis Big Boy to serve the film its dose of chaotic energy. This is possibly the actor’s most scream-heavy role, which is pretty stiff competition in a filmography that includes Scarface and Any Given Sunday. Even under prosthetics, nothing stops the actor from barking commands at Tracy, his bumbling goons, and his reluctant new gangster moll, Breathless Mahoney. Flanking Pacino are a number of famous faces, some almost unrecognizable under layers of makeup, like Paul Sorvino, Dustin Hoffman, Dick Van Dyke, Mandy Patinkin, and James Caan. But no one, not even the calm, cool-headed Tracy, can hold a candle to the fiery rage of Big Boy’s apoplectic tantrums.

DANNY ELFMAN AND STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S SCORE IS UNFORGETTABLE

Batman may have paired up composer Danny Elfman with Prince, but Dick Tracy brought Elfman’s bombastic orchestral superhero theme music together with Stephen Sondheim’s sensitive and catchy Broadway-esque tunes. Elfman’s opening theme captures the danger, romance and adventure the movie has to offer; though the score vaguely sounds like his theme for Batman, there are no ominous notes of doom and gloom. Instead, there’s a sense of mystery and grandiosity, as well as a frenetic feel, as if Tracy were searching for Big Boy in the sheet music. Then, it swells to the romantic ties between Tracy and Trueheart, a constant throughout the story.

Madonna and Sondheim round out the film’s music with a set of five show-stopping numbers, including “Sooner or Later” and “Back in Business.” The former is a bluesy number that explains Breathless’ insistence on seducing Tracy away from Trueheart because she “always gets” her man, while the latter is an upbeat jazz song that comes at an inopportune time for Tracy, and they make up two more reasons Dick Tracy is so fun to watch all these years later.

THE MOVIE IS FULL OF CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD REFERENCES

(Photo by Buena Vista Pictures)

Matte paintings aren’t the only old Hollywood tricks up Beatty’s yellow sleeves. Beatty, who had come to Hollywood in the waning days of the studio era, incorporated a number of homages to classic movies, the most noticeable of which is Breathless Mahoney, a film noir-inspired femme fatale given a Marilyn Monroe-inspired ‘do. In one scene, she’s even wearing a two-piece white suit that looks a lot like one of the costumes Rita Hayworth wears in Gilda, in which she plays the new wife of a club owner who, like Breathless, also sings and flirts with the main character.

From its start, the comic series had always been criticized for its violence, and the movie version is no different. There are car explosions, shootouts, attempted (and successful) murders, and lots of gun pointing between cops and criminals. Since Dick Tracy’s comic strip debuted around the same time as gangster movies like The Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) hit theaters, it’s also probable that Beatty incorporated those influences into Dick Tracy decades later.

The two aforementioned Sondheim songs, “Sooner or Later” and “Back in Business,” play over musical montages, each tracing the rise and fall of our hero. In one set of the montages, it’s Tracy breaking up Big Boy’s racket at every turn, cut in-between shots of the increasingly exasperated mob boss and newspaper headlines and radio announcers regaling Tracy’s successes. In “Back in Business,” Tracy’s been framed and locked-up, leaving the gangsters to regain control of the city while he stares hopelessly at the ceiling. But when Elfman’s score swells again, it’s Tracy’s turn to get back to business.

In a way, Dick Tracy is a movie of its time and outside of it, a film about a 1930s hero remade with as much leniency towards violence and sex as a 1990s PG-movie would allow. It’s a pastiche of nostalgia boiled down to its bare elements: good and bad, love and lust. It might have been an otherwise forgettable entry in the early days of movies based on comic characters, but Beatty and his team made it a cult favorite. There are few other movies that work as hard to make the real world look hand-drawn, to recreate each minute detail down to its monochromatic costumes, set decor and matte paintings, to recreate Tracy’s world from the page to the screen, and it’s all the more unique for it.

Where You Can Watch It Now

FandangoNOW (rent/own), Vudu (rent/own), Amazon (rent/own), Google (rent/own), iTunes (rent/own)

Dick Tracy was released on June 15, 1990.