Hail to the King: How Army of Darkness Cemented Bruce Campbell’s Cult Icon Status

Sam Raimi's third Evil Dead film flipped the franchise on its head but succeeded, thanks to Campbell's charisma and Raimi's inventive directing.

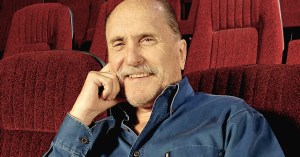

(Photo by Universal courtesy Everett Collection)

There will never be another Adam West. The pop icon helped introduce multiple generations of children like myself to camp, kitsch, and meta-humor through his portrayal of the 1960s television Batman, then rode that post-modern wave as the star of previous Simpsons Decade entry Lookwell, a particularly inspired guest star on The Simpsons, and the Mayor in Family Guy.

West didn’t disappear into the characters he was playing so much as the characters he played disappeared inside his own big, cartoonish persona, with its tongue-in-check machismo and hypnotically stylized line deliveries. Everything West did on Batman came with a wink and ironic quotation marks. He was at once a comic book superhero kids could root for and an arch, sardonic comment on the ridiculousness of the comic book world and its colorfully attired, gleefully preposterous inhabitants.

If you were looking for a contemporary equivalent, it would be hard to beat fellow trash culture icon Bruce Campbell. Like West, Campbell is at once a legitimately kick-ass action hero and a campy parody of lantern-jawed, old school heroism. In 1993’s Army of Darkness, one of the sacred texts in the Church of Bruce Campbell, the cult god plays a fairly familiar cultural archetype: the wisecracking, secretly noble loner who just wants to be left alone but keeps getting pushed into heroism by circumstance.

|

(Photo by Universal Pictures courtesy Everett Collection) |

Campbell dominates the movie to such a degree that it sometimes feels like a one-man show. |

It’s an archetype perfected by Harrison Ford, Humphrey Bogart, and Bruce Willis that allows them to exist both inside and outside of the action. The warped genius of Campbell’s persona is that instead of going lean and minimalist and restrained, he moves in the opposite direction, making Ash Williams, the iconic hero of the Evil Dead series, a wonderfully outsized cartoon character — part John Wayne, part Elvis, part Jerry Lewis, part Bugs Bunny, and 100 percent Bruce Campbell. Heck, just as Adam West is Batman on some level, Campbell is Ash, so much so that Army of Darkness’ opening credits explicitly posit Campbell (afforded above-the-title credits here, appropriately enough) versus the Army of Darkness rather than the character he plays.

Army Of Darkness is many things. It’s a gothic, splatter-comedy take on A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court. It’s a film that finds gleeful common ground in the geek-friendly canons of H.P. Lovecraft, who gave the world the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis, a book of infinite and often sinister magic that figures prominently in the plot here, and Ray Harryhausen, the stop-motion animation wizard who helped bring to life the fantastical creatures of Jason and the Argonauts and the original Clash of the Titans.

Army of Darkness is also one of the great departures in sequel history. After all, when you think of places the third entry in a low-budget horror-comedy trilogy could go, “time-traveling fantasy adventure-comedy with strong elements of the Three Stooges and Monty Python” probably isn’t the first thing that springs to mind.

But it doesn’t just begin — and then proceed — in a vastly different place than its predecessors. It keeps shifting genres and styles, united by an all-consuming goofiness, Campbell’s campy magnetism and physical comedy chops, and director Sam Raimi’s frenetic camera, which zooms around everywhere, favoring extreme comic book compositions and audacious, extensive use of steadicam to give the proceedings a lunatic air of runaway forward momentum.

Above all, Army of Darkness is a love letter from Raimi, who also co-wrote the film, to his favorite leading man, Bruce Campbell, and the best Bruce Campbell vehicle imaginable. It represents a triumph of old-school craftsmanship in terms of direction, special effects, stop-motion animation, costumes, props, and production design. Yet Campbell dominates the movie to such a degree that it sometimes feels like a one-man show.

That might be because Campbell doesn’t just play Ash, the unforgettable hero of the series and one of the most iconic and beloved characters in pop culture. He also plays tiny little versions of himself and, at one point, he plays both Ash and a temporary conjoined twin who eventually splits off and becomes his double, Evil Ash. If this makes the movie sound crazy and demented and over-the-top, that’s because it is.

Ash begins the film at a low ebb. “It’s 1300 A.D and I’m being dragged to my death. It wasn’t always like this,” he confides via narration. Even as he’s tortured and tormented in the blazing sun of a world that is not his own, he still somehow manages to inject a little Bruce Campbell swagger into his words. But before all of this happens, he lives in our world and works at a K-Mart-like store called S-Mart in housewares. He seems more pleased with his life than anyone working in a big box store has any right to be, which is part of why he’s seriously pissed when he’s hurled through time and ends up in the middle of a skirmish between King Arthur (yes, that King Arthur) and Duke Henry.

|

(Photo by Universal Pictures courtesy Everett Collection) |

The violence alternates between ingenious gore and the kind of cartoon mayhem found in Looney Tunes. |

Ash proves his heroism with more than a little help from his shotgun and chainsaw, the latter of which he attaches to the stump where one of his hands formerly existed, like something out of David Cronenberg’s wildest fantasies. Possessing such fantastical instruments in 1300 is enough to make someone a hero, if not a god, but since this is an Evil Dead movie, Ash must first endure a hilarious gauntlet of slapstick abuse before he can rise up and defeat an army of the dead.

Accordingly, Ash gets it from all directions, suffering for our amusement. In a particularly surreal comic set-piece homage to Gulliver’s Travels, the aforementioned horde of tiny, sinister little Ashes subdues and torments big Ash like so many Lilliputians. The violence here alternates between ingenious gore and the kind of cartoon mayhem found in Looney Tunes.

In order to return home, Ash learns he must retrieve the magical tome known as the Necronomicon, but something goes awry, and Ash finds himself pressed into service as a makeshift general waging war against an undead army of skeleton men. The series, which began as a wild, scrappy, low-budget horror-comedy, somehow became bigger, broader, weirder, and more ambitious until it evolved into a crazy cross between a medieval war movie filled with epic clashes and the most audacious dark comedy Ray Harryhausen never had the opportunity to make.

It is no criticism to say that Army of Darkness is boldly, unapologetically, even transcendently silly, a horror-comedy with the soul of a Three Stooges short. In fact, it’s high praise. Movies do not get much sillier than Army of Darkness, particularly when they contain this much gleeful, imaginative carnage.

Campbell presides over these proceedings with a grin, a wink and an excess of cheeseball charisma. He’s ten times larger than life. He’s Clint Eastwood to Sam Raimi’s wildly kinetic Sergio Leone, Kurt Russell to his John Carpenter. Army of Darkness represents the apex of one of the all-time great collaborations in American genre filmmaking.

The wonderful thing about making a movie rooted in the infinite horrors of the world H.P Lovecraft created, as Army of Darkness and the first two Evil Dead movies are, is that anything is possible. Consequently, one of the many exciting things about Army of Darkness and the crazy, maverick energy Raimi and Campbell bring to it is that it realizes that potential to a remarkable degree. It’s astonishing how many inspired ideas Raimi and Campbell fit into 81 crazily dense and densely crazy minutes.

Raimi and his long longtime friends and collaborators here, like Campbell, who co-produced, were used to working miracles on tiny budgets, so while the budget for a movie like this or Raimi’s earlier Darkman might be modest by major studio and genre standards, it’s all the money in the world for independent types like them.

|

(Photo by Universal Pictures courtesy Everett Collection) |

They made a movie with the production values of an A-list studio film and the soul of a demented drive-in cheapie. |

As a result, Army of Darkness feels like the work of scrappy outsiders who have finally been given the resources to realize everything they’ve ever dreamed of cinematically. They made a movie with the production values of an A-list studio film and the soul of a demented drive-in cheapie.

Watching Campbell’s legendary performance in Army of Darkness, I found myself wondering why he never made the leap from cult hero to major movie star. Why wouldn’t filmmakers in 1993 want to cast him in everything once they saw all that he could do as a leading man, co-star, slapstick comedian, action hero, one-man double act, and singularly brilliant parody of an action hero? How could a performance this groovy not lead to big paydays in hit movies? Why has Campbell spent much of his career in either small roles in big movies or big roles in very small movies?

Then again, like West, Campbell is such a unique performer that his big personality can overshadow and overwhelm a film. That’s why perhaps the actor’s second-best role (third, if you include being Bruce Campbell) is playing a geriatric and melancholy Elvis Presley in Bubba Ho-Tep. There’s an awful lot of Elvis in Ash as well, particularly in his unique brand of sweet-talking the ladies. Elvis is the rare role big enough for Campbell.

Adam West never became a major movie star either. Heck, Lookwell, one of his funniest, most important, and most influential projects, never even made it past the pilot stage. But when West died, he was beloved, and it seems safe to assume that no matter what Campbell does in the decades ahead, unless his life takes some manner of dark, Bill Cosby-like turn, the same will be true of him. Bruce Campbell is not the biggest star, but to the cultists who love him, it gets no bigger, and that’s not just a reference to his glorious penchant for over-acting.

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin