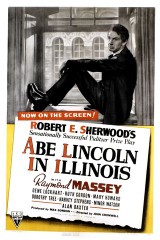

Abe Lincoln in Illinois was a Pulitzer-winning hit on the stage before it arrived in theaters, and the film adaptation did right by its source material, earning a pair of Academy Award nominations — including a Best Actor nomination for Raymond Massey, who reprised his stage performance as Honest Abe on his way to the White House. (Fun trivia note: Ruth Gordon, who went on to win an Oscar for her performance as Minnie Castavet in Rosemary’s Baby, makes her screen debut here as Mary Todd Lincoln.) “It’s a grand picture they’ve made from Robert Sherwood’s Pulitzer Prize play of two seasons back,” enthused Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times. “A grand picture and a memorable biography of the greatest American of them all.”

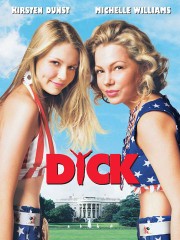

With a pair of bikini-topped girls on the poster, the involvement of someone named Deep Throat, and a title like Dick, you might expect something other than a cheerful political parody from director Andrew Fleming’s 1999 release. But all winking aside, Dick is actually a fairly clever re-imagining of the Watergate scandal, with a pair of teenage girls (played by Michelle Williams and Kirsten Dunst) who stumble into jobs as White House dog walkers after unwittingly ruining the break-in — and subsequently wind up altering the course of the entire administration. Mused Sue Pierman of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, “The film is such a delight not only because it’s clever, but because it so perfectly captures the era.”

Ron Howard’s best-reviewed film in ages, 2009’s Frost/Nixon adapts the Peter Morgan play that dramatized British broadcaster David Frost’s (played by Michael Sheen) efforts to secure and sell a series of TV interviews with the politically exiled former president (portrayed by Frank Langella). Although plenty of pundits took umbrage at the way Morgan’s screenplay took liberties with the actual events that inspired the film, for the vast majority of critics, Frost/Nixon‘s flaws seemed pretty minor when weighed against the script, direction, editing, completed picture, and Langella’s performance — all of which received Oscar nominations. For the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Steven Rea, it all added up to “A must-see for political junkies, history buffs, and folks still fascinated by the paranoia-fueled follies of the twitchy, sweaty, decidedly uncharismatic 37th president.”

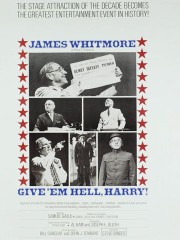

Samuel Gallu’s hit play came to the screen with this 1975 film, which used nine cameras to capture a tour de force performance from the show’s one-man cast. James Whitmore earned Best Actor nominations from the Academy Awards as well as the Golden Globes for his portrayal of Harry S. Truman, which revisited highlights from the 33rd President’s career — and benefited greatly from post-Watergate America’s yearning for leaders they could trust. Roger Ebert captured this feeling in his review, praising Give ‘Em Hell, Harry! for its “nice, wicked partisan spirit sure to delight Democrats and inspire Republicans to wonder glumly why Richard, Dwight, Herbert, Calvin and Warren, not to mention Gerald, don’t seem to lend themselves to this treatment.”

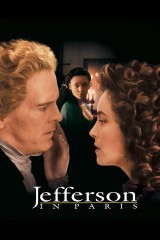

Could Thomas Jefferson have projected Nick Nolte’s air of rumpled insouciance in a mugshot? We’ll never know for sure, but we do know Nolte is capable of pulling off a pretty solid facsimile of our nation’s third president. The evidence: 1995’s Jefferson in Paris, which imagines what may have transpired during his French ambassadorship during the years leading up to his eventual election — specifically, his alleged affairs with Maria Cosway and Sally Hemings. Directed by James Ivory and featuring a terrific cast that included James Earl Jones, Thandie Newton, and Gwyneth Paltrow, Jefferson seemed like critical catnip; alas, most scribes turned up their noses at the finished product’s sluggish pace and scattered screenplay. James Berardinelli of ReelViews acted as a voice of dissent, arguing, “Though it may be occasionally slow-moving and perhaps a half-hour too long, this film is put together with care and a mindfulness of quality.”

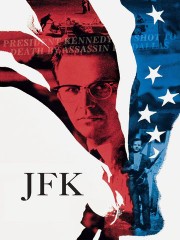

A two-time Oscar winner and controversial smash hit for director Oliver Stone, JFK reconstructs John F. Kennedy’s assassination and then spends most of its epic 189-minute length sifting through the wreckage, treating the killing as a murder mystery that New Orleans D.A. Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) doggedly attempts to solve at any cost. With an impeccable supporting cast that included Sissy Spacek, Kevin Bacon, Tommy Lee Jones, and Gary Oldman, as well as a screenplay that challenged long-held assumptions about Kennedy’s death, JFK reignited interest in the assassination, eventually leading to new legislation that ordered a reinvestigation and promised that all documents related to the killing would be made public by 2017. And while many critics agreed that the movie could have benefited from a more rigorous approach to the facts, it remains, in the words of the Washington Post’s Desson Thomson, “A riveting marriage of fact and fiction.”

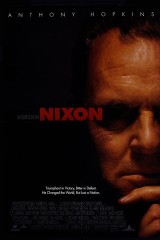

Part of the Tricky Dick trifecta on this list, Oliver Stone’s Nixon gave us Anthony Hopkins as the disgraced former president and Joan Allen as his wife Pat — and while the 192-minute political epic failed to generate much heat at the box office, both Hopkins and Allen received Oscar nominations for their work in the film, which follows a non-linear path through Nixon’s life and career, taking viewers from his California youth through his resignation. “What it finally adds up to,” argued Janet Maslin of the New York Times, “is a huge mixed bag of waxworks and daring, a film that is furiously ambitious even when it goes flat, and startling even when it settles for eerie, movie-of-the-week mimicry.”

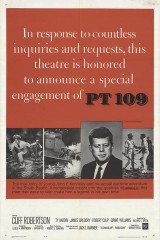

The first theatrical release inspired by a sitting president, 1963’s PT 109 used Vincent Flaherty and Howard Sheehan’s nonfiction bestseller about John F. Kennedy’s heroics during World War II as the basis for a war film starring Cliff Robertson as JFK, James Gregory as his crusty commander, and a young(er) Norman Fell as one of his crewmates. Made with no shortage of reverence for its subject — and White House veto power over the director and star — PT 109 struck many critics as too long and dull to recommend during its theatrical run, but most scribes found something to enjoy. As Allmovie’s Craig Butler pointed out, “Not everyone was involved with the major assaults; many spent their time risking their lives in places and situations of which most people are totally unaware, and it’s a nice change of pace to see this aspect of the war dramatized.”

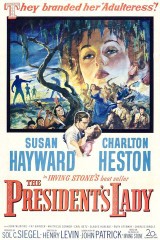

Before he played Moses, John the Baptist, or Michelangelo, Charlton Heston portrayed Andrew Jackson in The President’s Lady, dramatizing the seventh President’s early years in a sweeping historical drama that centers on his marriage to Rachel Donelson Robards. Arguably more interesting than most presidential unions, Jackson’s relationship with Robards was complicated after the lovebirds discovered that their marriage was technically invalid on account of the fact that her previous husband had lied about filing for divorce, thus clouding Jackson’s political ambitions with accusations of bigamy. “Through it all,” observed Variety, “Charlton Heston supplies the kind of ammunition to this film that is as loaded as any carbine slung across his broad shoulders. It is a forthright steely-eyed portrayal.”

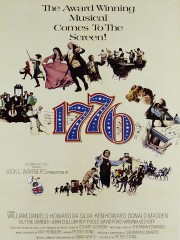

A musical about the founding fathers? It might sound like a Family Guy sketch, but 1776 is actually very serious — and although it arrived in theaters a few years too early to take advantage of bicentennial fever, director Peter H. Hunt’s song-and-dancefied look at our nation’s birth found critics in a generally forgiving mood. How can you argue with a musical starring Ken Howard as Thomas Jefferson? Vincent Canby of the New York Times couldn’t — although he groused that “the music is resolutely unmemorable” and “the lyrics sound as if they’d been written by someone high on root beer,” he had to concede that this adaptation of the hit 1969 play “insists on being so entertaining and, at times, even moving, that you might as well stop resisting it.”

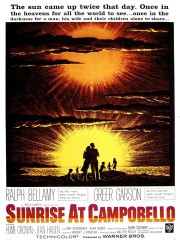

A key figure in some of the most crucial events in American history, Franklin Delano Roosevelt led an eminently biopic-worthy life — but 1960’s Sunrise at Campobello sidesteps most of his time on the world stage, opting instead to concentrate on the difficulties he faced in the weeks after suffering partial paralysis at the age of 39. Ralph Bellamy stars here as FDR, reprising his role in the hit stage run of the Broadway play, alongside Greer Garson (who earned an Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe for her performance) as Eleanor Roosevelt. For most critics — who were, along with the rest of the country, learning the extent of the former President’s health struggles for the first time — the end result was well worth watching. “Ralph Bellamy’s performance of Mr. Roosevelt is every bit as strong, as full of feeling and characteristic gesture, as Mr. Bellamy made it on the stage,” wrote Bosley Crowther in the New York Times. “The picture he gives us of a strong man enduring a dark Gethsemane and coming through it with cheerfulness and courage is one of the finest of this year on the screen.”

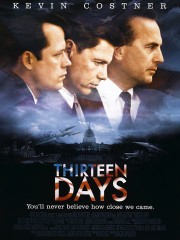

Nearly a decade after he scored a huge hit with JFK, Kevin Costner starred in another film that drew inspiration from events surrounding the Kennedy administration: Thirteen Days, which found Costner playing presidential aide Kenneth O’Donnell alongside Bruce Greenwood (JFK) and Steven Culp (Bobby Kennedy) in a tense behind-the-scenes dramatization of what went down in the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. While it wasn’t a huge hit during its theatrical run, Days scored with critics such as Eric Harrison of the Houston Chronicle, who mused, “Who would’ve thought this nearly 40-year-old piece of history could be turned into such a riveting motion picture?”

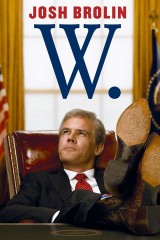

The most recent chapter of Oliver Stone’s presidential trilogy, W. served George W. Bush — who was wrapping up his second term while it was filmed — with a somewhat muted, surprisingly sympathetic biopic that traced his occasionally haphazard rise from political scion to oil baron and back again. While Josh Brolin earned near-universal praise for his work in the title role, critics found W. as a whole a little harder to take, citing its laconic pace and insufficiently hard-hitting approach as particularly troublesome flaws. For others, however, it proved a warm, fairly witty farewell for the GWB years; as the Chicago Tribune’s Michael Phillips put it, “The film may be ill-timed, arguably unnecessary and no more psychologically probing than any other Stone movie. But much of it works as deft, brisk, slyly engaging docudrama.”

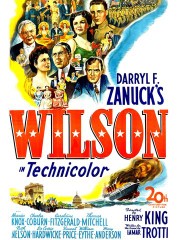

A prolific legislator, successful — albeit occasionally begrudging — proponent of progressive causes (including women’s suffrage), and dedicated diplomat, Woodrow Wilson offered producer Darryl F. Zanuck plenty of material for a biopic — and Zanuck obliged, turning the 28th President’s life into the 154-minute epic known simply as Wilson. Sadly, in spite of its inspiring source material (and generally positive reviews), Wilson was a costly flop; according to the film’s Wikipedia entry, “its failure upset him to the point that he forbade any of his employees from ever mentioning the film in his presence again.” Still, the movie earned an impressive 13 Academy Awards, winning six. “Zanuck, fresh from his experiences of WWII, was keen to make a movie which addressed the problems of the age,” explained Time Out. “The result’s handsome, worthy and solemn.”

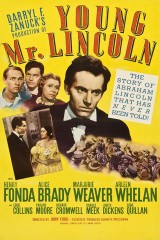

Offering a somewhat fictionalized version of real-life events, Young Mr. Lincoln blends the 16th President’s early years into some vintage courtroom drama with surprisingly successful results. Starring Henry Fonda as Lincoln, the film begins with the chance encounter that sparks his journey from humble shopkeeper to skilled attorney, culminating in a court case that finds young Mr. Lincoln saving a couple of men framed for murder — and winning Mary Todd’s heart in the process. Eventually enshrined in the National Film Registry, Young Mr. Lincoln boasts a perfect Tomatometer rating thanks to reviews like the writeup printed by Douglas Pratt of the Hollywood Reporter, who enthused, “Fonda’s physical presence throughout the film is a thing of magic, as he seems to glide from one position to the next, never looking awkward even when he is bent in three places to fit within the frame.”