The Ben Stiller Show: How Judd Apatow and Ben Stiller Turned Pop Culture on its Head in 1992

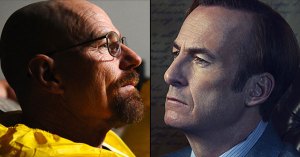

The sketch comedy show featuring Bob Odenkirk, Janeane Garofalo, and Andy Dick helped define the comedic sensibilities of Generation X.

Like Chris Elliott (whose Get a Life was the first entry in this series), Ben Stiller is a child of show business in more ways than one. Where Elliott’s father is famously beloved cult pioneer Bob Elliott of Bob & Ray fame, Stiller is the product of a bona fide comedy team: Stiller & Meara. For Stiller and Elliott — just as it is for everyone — pursuing a life in comedy was a huge gamble, but it was also the family business and one both men entered early.

Stiller was also a child of show business in a less literal sense. His parents might be Jerry Stiller (of Seinfeld and King Of Queens fame) and Anne Meara, but judging from his eponymous Fox sketch show, Stiller’s TV and VCR were clearly cherished companions as well. The product of a generation that grew up with VCRs and cable television, he was consequently able to explore the cultural past, particularly the embarrassing parts, in a new and unique way.

The Ben Stiller Show, which ran from September of 1992 to January of 1993 on Fox (and followed an MTV series of the same name that ran several years earlier), had a love-hate relationship with show business, particularly television and comedy, that brings SCTV to mind. The groundbreaking Canadian sketch classic, an influence on Stiller’s show, similarly depicted television less as an important component of modern life than as life itself — a tacky, gaudy, commercial-selling wasteland that’s also the source of joy and pleasure.

One of The Ben Stiller Show’s signature moves was to use the reassuring tackiness of the pop culture past to undercut the pretentiousness of the present. In the hands of Stiller and his associates, the Monkees were reborn as the Grungies, a dead-on parody of second-generation Nirvana and Soundgarden clones shot in a perfect approximation of The Monkees’ manic, cutaway- and sight gag-filled visual style. It’s a signature sketch that’s audacious enough to include one band member who appears to be in a perpetual state of fuzzy, heroin-fueled non-comprehension. It’s hard to believe a primetime network show got away with that in 1992, but that’s probably because The Ben Stiller Show threw so much darkness at censors that a fair amount had to slip through.

|

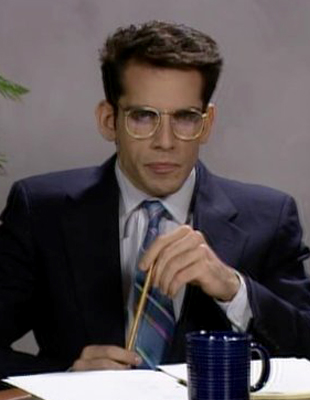

Even as Stiller makes fun of good-looking, empty-headed superstars, he also has the looks to pull off playing people like Tom Cruise. |

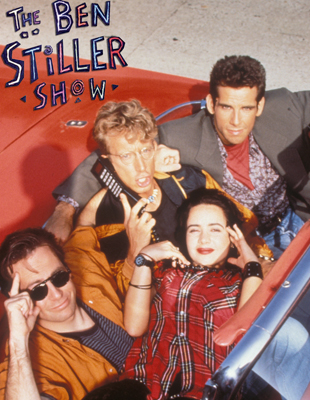

Stiller gravitates toward crazed narcissists who take themselves too seriously. Pompous exemplars of pop culture pretension like Oliver Stone, Jim Morrison, and Bono are just cornball showmen out to make a buck and remain famous, and The Ben Stiller Show knocked them down to size. As Colin Quinn notes teasingly, but with an underlying sincerity, even as Stiller makes fun of good-looking, empty-headed superstars — Bono fits the bill — he also has the looks to pull off playing people like Tom Cruise, who’s portrayed grinning, mugging, and winking his way through a one-man show based on his movies, and later in a scouting-themed parody of A Few Good Men. Stiller is a fascinating combination of leading man and character actor, most comfortable when buried under layer upon layer of latex, which the show also uses frequently to transform the rest of its astonishingly talented cast (Janeane Garofalo, Andy Dick, and Bob Odenkirk).

The stylistic aspirations of most sketch shows begin and end with filming scripts, but Stiller was already making movies and obsessing over the details of those short films in ways that are rare for television, particularly for the time. When the show slots Charles Manson into Lassie’s role in a parody of the venerable children’s favorite, it’s hilarious — not just because Bob Odenkirk’s wild-eyed, furiously intense take on Manson is so scarily committed, but also because the show gets the details right, perfectly recreating the look of 1950s television (Lassie in particular).

Fellow Stiller Show stars Andy Dick and Janeane Garofalo would subsequently become as well-known for their offscreen personae as their onscreen work. Dick’s private life has overshadowed his career, but for a man with a reputation as an attention-starved trainwreck, he comes across as a consummate professional and team player here. Garofalo is similarly adept at playing characters from across the pop culture spectrum, with a surprising affinity for blandly wholesome housewife types. The Ben Stiller Show captured Garofalo at the height of her hipness, when she was the crush of countless nerdy teenage boys, as well as the crush/role model of just as many cynical teenaged girls. This was her cultural moment, and she made the most of it. As for Odenkirk, he would have ruthlessly dominated the cast of any other sketch show — but then, The Ben Stiller Show wasn’t just any sketch show.

Re-watching the Stiller Show today is like mainlining 1992. Yet if it’s steeped in the era of Lollapalooza and Check Your Head, ripped jeans and flannel, it’s also influenced by the Shriner’s Club and Canter’s Deli. Stiller is his parents’ son, so it’s not surprising that one of the show’s most commonly used recurring characters is a fast-talking, ethically-challenged agent (the kind that has been a staple of American comedy at least since vaudeville) forever pitching ridiculous ideas to his frustrated clients, or that when playing the part, Stiller sports a huge smile that seems only partially attributable to the role.

The Ben Stiller Show boasts the energy and exuberance of one of those transcendent debut albums where a band says everything they have to say the first time around, rendering the rest of their careers an extended anticlimax. There was something about the youth and the chemistry of the cast that made them more than the sum of their considerable parts. If the cast of the show were a band, then Stiller would be the frontman and lead singer, Garofalo would be the tartly adorable bassist, Andy Dick would be the wild-man drummer (although his persona was much more mild at the time), and Bob Odenkirk would be the moody, virtuoso guitarist with the weird avant-garde jazz side project.

|

Re-watching the Stiller Show today is like mainlining 1992. |

The show’s premise found Stiller — playing a goofier, less successful version of himself — interacting with the cast or with a guest star as he introduced sketches and short films, many of them deeply rooted in the pop culture of the day. The joke is that Stiller is an exuberant, over-eager little puppy desperate to make his mark in show-biz who keeps getting swatted down by actual show business players like Garry Shandling (who appears twice and would employ much of the show’s cast and crew for The Larry Sanders Show), yet it isn’t truly convincing; even then, it was evident Stiller was going places. In hindsight, it’s not surprising that a man able to create and star in a project as impressive and ambitious as The Ben Stiller Show would go on to become a major movie star and director.

Parodies of The Heights and the briefly popular, insultingly salacious dating show Studs irrevocably timestamp The Ben Stiller Show as a product of 1992 and 1993, but a monster-themed parody of a then-current movie (Woody Allen’s almost invasively raw relationship drama Husbands & Wives) is one for the ages. God bless The Ben Stiller Show, which clearly put a lot of thought into imagining what Sydney Pollack’s troubled character in Husbands & Wives would look and act like if he was Frankenstein’s monster, while Andy Dick’s disarmingly charming take on Woody Allen as a mummy suggests that both Dick and Allen would somehow be more sympathetic if they were undead ghouls. The Husbands & Wives parody is characteristically obsessive in its attention to detail, right down to the font it employs for its opening credits and its faithful recreation of the film’s quasi-documentary format.

The show grew even more conceptually ambitious as it progressed. David Cross joined the writing staff and played a few bit parts, and the end of The Ben Stiller Show anticipated the very beginning of Mr. Show in the way that elements from one sketch would reappear in another, making it a universe unto itself.

The overall aesthetic is the mash-up, short attention span sensibility of the remote control, with its seemingly unlimited options (the vast majority of them unappealing, alas) and endless tapestry of familiar faces returning through the decades even as they drift further and further from their initial fame.

The Ben Stiller Show makes Stiller’s show business ambitions a self-deprecating joke in a way that never masks his clear drive. It’s not surprising that Stiller made the leap from TV to film with Reality Bites, a movie about people filtering their life through the distorting lens of television, and then reunited with Stiller Show co-creator, writer and executive producer Judd Apatow for The Cable Guy, yet another movie that revisits the same themes. Apatow and Stiller never stopped being obsessed with TV and pop culture, enormous egos, and our campy, embarrassing past — it just took different forms.

|

The Ben Stiller Show makes Stiller’s show business ambitions a self-deprecating joke in a way that never masks his clear drive. |

Despite the talent involved, The Ben Stiller Show proved a one-season wonder, one of those sad unicorns too good for our degraded world, but it did exactly what it set out to do: it helped define Generation X’s comic voice, a principled cynicism and a complicated relationship with nostalgia and the pop culture of its childhood. It went on to win an Emmy for writing after it had already been cancelled, a weirdly appropriate consolation prize. But given its star and co-creator’s voracious ambition, it served as a calling card, an elaborate and impressive illustration of what Stiller, his cast, and his writers could all do.

On that level, it’s an extraordinary success. Stiller has had a career full of highs and lows, but triumphs like The Cable Guy and Tropic Thunder have a manic satiric spark that can be traced directly back to The Ben Stiller Show — as can many of Judd Apatow’s later critical and commercial triumphs. And Mr. Show followed very organically in the Stiller Show’s footsteps, to the point where it almost feels like a continuation.

Stiller ultimately became the Hollywood titan and show business powerbroker he spent The Ben Stiller Show satirizing, as did co-creator Apatow, whose deep love of comedy history informs every frame of the show where he first found his voice as a television auteur. Apatow would later work on The Critic, The Larry Sanders Show and Freaks & Geeks in the 1990s alone, meaning we’re going to see a lot more of him here. That’s not a bad run, particularly considering his biggest commercial successes were still to come.

The Ben Stiller Show was a show for people who didn’t just love to laugh, but loved comedy. It was for people who saw comedy as a sacred tradition, an important history to be studied and savored, a sacred calling and a state of mind. It was for comedy geeks with the misfortune to arrive in a pre-comedy geek era. Stiller and Apatow, once ambitious outsiders itching to break into the big time, have become two of the biggest, most bankable people in modern comedy, thanks in part to the plucky, overachieving show they dreamed up together. Today, The Ben Stiller Show stands as both one of the defining comedies of Generation X and a crucial bridge between the campy, self-referential comedy that preceded it (it doesn’t seem coincidental that cast members from both the 1960s Batman and the Monkees contribute cameos that double as benedictions/torch-passing) and subsequent comedies similarly steeped in a rich comic tradition.

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin