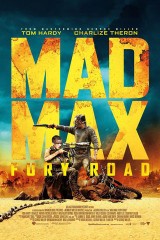

21 Most Memorable Movie Moments: “Remember Me?!” from Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Director George Miller breaks down the moment that Furiosa unleashes her anger on Immortan Joe and why Charlize was the only actor for the job.

Watch: Director and co-writer George Miller on the making of Mad Max: Fury Road above.

In 2019, Rotten Tomatoes turns 21, and to mark the occasion we’re celebrating the 21 Most Memorable Moments from the movies over the last 21 years. In this special video series, we speak to the actors and filmmakers who made those moments happen, revealing behind-the-scenes details of how they came to be and diving deep into why they’ve stuck with us for so long. Once we’ve announced all 21, it will be up to you, the fans, to vote for which is the most memorable moment of all. In this episode of our ‘21 Most Memorable Moments’ series, Mad Max: Fury Road director and co-writer George Miller reveals how his wild road movie – and the female warrior at its center – came to be.

VOTE FOR THIS MOMENT IN OUR 21 MOST MEMORABLE MOVIE MOMENTS POLL

The Movie:

Looking for a definition of that cursed Hollywood term, “Development Hell”? Look no further than Mad Max: Fury Road, the movie that came three decades after the last Mad Max film and which took writer-director George Miller almost 20 years to make. Over the course of decades, production was famously waylaid by global events (September 11, the Iraq War), other productions shifting the filmmaker’s focus (Happy Feet and its sequel), and then by nature: things were all set to go for shooting in Broken Hill, Australia, when mass rains turned the landscape from something that looked like a post-apocalyptic wasteland into something more like FernGully. The movie did eventually shoot in Namibia, though, and after years in editing – overseen by Margaret Sixel, Miller’s collaborator and wife, who would win an Oscar for the film – was released in 2015.

The acclaim was instant and loud; the pain had been worth it. Critics hailed Miller’s 30-years-later sequel to Beyond Thunderdome as a bold and visionary achievement, with a relentless energy and practically-achieved action sequences that were beyond anything they’d seen before. (It is number one on our list of 140 Essential Action Movies.) In a bold move, Miller moved Max Rockatansky (once played by Mel Gibson, here played by Tom Hardy) into an almost-supporting role, with Charlize Theron the true lead as Imperator Furiosa, the warrior on a mission to free a group of enslaved wives from their master, the evil Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne). Fury Road‘s themes are big and weighty, its engines loud and mighty, and its impact has been huge. Here, Miller talks us through the moment he got the idea for this movie about an endless desert chase, dealing with the setbacks that delayed it, and how he finally got started making his vision a kinetic reality.

“The idea was simple: What if there was a chase and what was at stake was very elemental and very human?”

“Ideas are banging around in your head all the time, and you keep pushing them away until some get more insistent. And that’s exactly what happened with Mad Max: Fury Road. I remember specifically, I was in Los Angeles, and I was at a traffic crossing. When the light went green to cross, I was walking across the road, and this idea popped into my head about what eventually became this Fury Road. By the time I got to the other side, I said to myself, ‘No way. I don’t want to do another Mad Max movie.’ And that’s what it was. The idea was very, very simple: What if there was a chase and what was at stake was very elemental and very human? In the old Hitchcock sense, the MacGuffin has to be very human. I thought, ‘Well, the best thing would be for them to be five or six women,’ and initially it was five to seven women being chased across the wasteland, pursued by a warlord, and Max gets caught up in their story.

“So, cut to months later, I didn’t give it another thought. I’m on that long flight home from Los Angeles to Sydney. It’s through the night over the Pacific and in those unguarded moments when you’ve got nothing else to do, the story played out in my head, at least a good half of it. I remember thinking, ‘Holy cow, this could work out OK!’ I landed in Sydney, and I went to my colleagues and I said, ‘Look, I think there’s another Mad Max sometime in the future.’ I didn’t know that it would be such a long time – that was in the late ’90s. But like all good stories, they really do insist on being made in some way. It’s Darwinian.”

Miller wanted to make the stakes as high as possible, and so the cargo was human. (Photo by Jasin Boland/©Warner Bros. Pictures/courtesy Everett Collection)

“The only reason that it’s five brides that are being chased by the warlord is that we couldn’t fit seven into a car.”

“In the Indigenous culture [in Australia], which is the oldest continuous culture that we have on the planet, one of the creation stories, or the common creation stories, depending on which part [of the country] you go to, is the story of seven sisters escaping some male principal, and it’s a malignant male principal. In the story, they help create the topography and all the nature around, and there’s a variation of that story all over Australia. It’s an oral tradition. It was only as an afterthought that I figured out, ‘Hey, wait a minute, we’re telling that story.’ The only reason for us that it’s five brides that are being chased by the warlord is that we couldn’t fit seven into a car, we couldn’t distribute all the detail of characters. We had to differentiate a lot of characters, and to try it with seven people would be more difficult.”

“We could do things we could never even dream of doing back 30 years before, when it was all analog and old-school.”

“I love action movies, I love chase movies. I think one could argue that they’re the purest form of cinema, in the sense that the syntax of cinema was developed pre-sound. I’m a big fan of the book written – I think back in the ’60s or ’70s – by Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By…, where he said this new language that we call cinema, which everybody can read now, is basically sorted out before the advent of sound. Because the cameras and the sound equipment became quite cumbersome, it took a long time for them to become agile again and we could get a kinetic cinema. And so, I’m very, very attracted to that. [Fury Road] was an opportunity to do basically three things: Number one, use a basic idea. Number two, to do a film that was almost constant action and see how much subtext, see how much people could read on the run. And the other big thing was, after 30 years, to be able to use the new technology available, new cameras, the new digital dispensation, so that we could do things we could never even dream of doing back 30 years before when it was all analog and old school, but yet still building on the skills we learned then.”

The movie existed on thousands of storyboards before there was a script. (Photo by Jasin Boland/©Warner Bros. Pictures/courtesy Everett Collection)

“When you’ve got something that is essentially not verbal and you’re trying to be very specific with your film language, the storyboard is the best tool…the film existed on 3,800 panels around the room.”

“The best way to render [an action movie] is not with the written word, but with storyboards. I remember when I first started making movies, I’d board them first, because that was the most immediate representation of the movie and what was swirling around in your head. Then I would do a boarded screenplay and turn it into a screenplay. And I thought, ‘Oh, this is an opportunity to do that.’ When you’ve got something that is essentially not verbal and you’re trying to be very, very specific with your film language, the storyboard is the best tool, at least for production. So after laying out the basic story, we boarded the film first. There was [co-writer] Brendan McCarthy, who serendipitously started to work on the film. There was [storyboard artist] Mark Sexton, and we all sat in a room and prepared all these boards.

“So in many ways, the film existed on a wall and 3,800 panels around the room. It was there always reminding me. Even when I was working on Happy Feet, I’d walk into what I called the Mad Max room, and there it was. It was a present thing, it wasn’t just in people’s heads at that point. But then the first setback was 9/11, and everything closed down, everyone was uncertain. It was very difficult to get the equipment we wanted, that we couldn’t get in Australia, and so on. Insurances went up.”

“We had unprecedented rains in Broken Hill. Instead of red harsh earth, we had basically a flower garden.”

“Warner Brothers had already seen [material for] Happy Feet, and they were saying, ‘Hey, listen, when can we do Happy Feet?’, which was also prepared at the same time. Once that happened, I said, ‘OK, let’s get into Happy Feet.’ Well, that’s four years gone right there. Then we got [Fury Road] up again, and then, I think it’s probably well known, we had unprecedented rains in Broken Hill [the area in far west New South Wales, Australia, where Miller planned to shoot]. Instead of red harsh earth, we had basically a flower garden, which was wonderful. And Lake Eyre, where we wanted to shoot, was now full of fish and frogs and pelicans.

“I was very familiar with Broken Hill, of course, because we’d shot Mad Max 2 there. But we had actually roads built, we had 150 vehicles there, our stunt crew was there. A lot of the stunts were prepared there. I mean, on the one hand, it was bad for Mad Max, but it was a wonderful thing to see, because what’s right under the earth, for the want of rain, is this amazing, amazing color and flowers, and they grew to waist high. I’ve got pictures of it. I remember driving along this dirt road and stepping off the road and filming. It went on for miles, just this lilac and purple and green, just went on for miles. So it was put off again. I finally ended up doing another Happy Feet, and then the planets aligned, and we went off and shot Fury Road.”

The Moment: “Remember me?”

Fury Road is ultimately Furiosa’s movie: It is she who drives the action and it is she who ultimately gets to annihilate the villain, Immortan Joe. The moment in which she does so may not be the most spectacular moment in a film full of visuals and stunts and violence that stun and dazzle, but it lingers for its ferocity and its intimacy – there is so much that is unsaid about their history and about the world of Mad Max when she simply says, “Remember me?,” and viciously kills Immortan. Miller here reveals that the line was not originally in the script, and was something Theron felt she wanted to say.

Theron and Miller on the set of Mad Max: Fury Road. (Photo by Jasin Boland/©Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection)

“She had all the attributes that Furiosa had, even though they’re from completely different worlds.”

“The thing that was contraband [in Fury Road] was human, and it was five wives, or ‘breeders’ as we called them, escaping a tyrant who sat on top of this dominant hierarchy. Their champion had to be a warrior. And if it was a male, it just wouldn’t work: It would be one man theoretically stealing five wives from another man. It had to be a female warrior, and hence Furiosa. The very first person who came to mind was Charlize. First of all, she’s got the acting chops. Secondly, she’s not somebody given to vanity. She’s already gifted by beauty, so she is very happy to go against that. But it goes much deeper than that. For instance, she was the one who said, ‘Look, I’d really like her to have no hair. If she were serious, she wouldn’t mess around with hair in the wasteland, with all the dust and so on.’

“But beyond that, she’s also someone who is very, very disciplined. She was trained in ballet and I know enough about ballet and dancers to know that they’re very tough people physically and very disciplined, with fantastic memory; I think they call it muscle memory nowadays, but fantastic memory and real understanding of where their bodies are in time and space. I learnt that particularly from doing the Happy Feet movies. Charlize had that.

“And then her own history, the way she came from South Africa, her own family history. I know she went to New York, became a dancer, which is another tough milieu to work in. And then she went to L.A. when she got injured and so on. She had all the attributes that Furiosa had, even though they’re from completely different worlds. And the theory proved correct of course, because she was Furiosa. I mean, stopped thinking about her as Charlize when we were out there in the heat and the dust and on those big vehicles. When she was driving them, I stopped thinking of her as Charlize and only saw her as the character.”

Theron was the first person Miller wanted for the role of Furiosa. (Photo by Jasin Boland/©Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection)

“She was determined to not do any action as if it were a female doing a man’s job. She said, ‘If I’m going to pick up a weapon, I want to shoot as if I’m really experienced.’”

“[Charlize would] walk out of the makeup van and roll around in the dust, just to get it in her skin and under her nails. Before we started the film, she said, ‘Look, I’ve got to tell you something. I hate dust on my hands.’ She has some sort of aversion to it. And I said, ‘Well, what are we going to do? Should we have wipes and things?’ She said, ‘No, no, it’s going to help me.’ The other thing she was determined to do was not do any action as if it were a female doing a man’s job. She said, ‘If I’m going to pick up a weapon, I want to shoot as if I’m really experienced.’ She had an aversion to guns, but she was determined to do it. ‘If I run, if I walk, if I hit somebody…’ You see the way she does things. I mean, that headbutt at the end of the movie: they’re difficult to pull off, and she just did it. I mean, she was scarily good in that scene.”

“We know that stuff happened [between them], but you can never be explicit about all that stuff. It would be an epic novel.”

“The film itself, there’s a lot of iceberg under the tip. I think one of the great concerns about the film is whether people could read enough [from the visuals and sparse dialogue] to get the story. We were never very explicit about everything. We knew something happened [with Immortan and Furiosa]. Here is a world in which people are commodities. They have the brand of the Immortan on their back; everybody in this story, including Max, we have to assume, has the brand of the Immortan on his back. Furiosa has it when we first see her; it’s on the back of her neck. And so we know that stuff happened, but you can never be explicit about all that stuff. It would be an epic novel. She is the one who finally in this…not so much a chase, but a race to get to the Citadel… she is the one who finds herself in the position closest to Immortan. And she uses this moment to hook this harpoon on his mask, which is a privilege in that world, because in some way that mask filters the toxic air, something available to him that others would not have. She takes that moment to say, ‘Remember me.’”

Miller says Theron came up with the line, “Remember me?!”. (Photo by Jasin Boland/©Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection)

“Charlize on that day said that she wanted to say the line. It wasn’t a written line… It was a little pause before the brutality of the moment.”

“[The moment] carries a huge amount of meaning to the character, and it implies a lot of grievance about their backstory. We have hints of it, we could speculate as to what it might be, but we don’t know at that moment all the details. But it therefore becomes somewhat allegorical. It could be all of those who have somehow had to struggle out of some sort of oppression at the hands of some tyrannical figure. She gets her vengeance in that moment, but the story of course is not done. And it’s a moment by the way, I think, is available only to her. I don’t think any other character could have done it. I remember the line. I remember Charlize on that day said that she wanted to say the line. It wasn’t a written line. She said, ‘Look, I feel like I really want to say it. OK by you?’ I said, ‘Great.’ It just hit a sweet spot in amongst that action, and it was a little pause before the brutality of the moment and the continuation of the action that was to come.”

The Impact: A Landmark Action Film

Fury Road was one of those rare films that felt like a classic the moment it was released; it did not need time to age well, and critics and audiences felt instinctively it was something special. Which explains the accolades: the movie won six Academy Awards, all for craft and technical categories, and was that rare action film to be nominated for Best Picture and Best Director. It made almost $400 million worldwide, which may not seem huge when compared to MCU box office numbers, but is a mighty haul for a non-superhero film – especially one as oddball and manic as this. But that’s almost beside the point.

Fury Road was singularly exciting. It was part of a franchise, sure – though one that had not been revisited since 1985 – but it felt wholly original and invigorating. At a time when CGI overload and repeated formulas had many lamenting a settling sense of sameness, and safeness, in blockbuster cinema, Miller and co. came in and blew everything up. They showed that a big-budget car-chase movie could feel as special and distinct as anything at your local arthouse cinema. No wonder recent news that three more Mad Max movies are on the way – including one centered on Furiosa – set the film world on fire. Let’s just hope we don’t have to wait 30 years to see them.

“We fade to black, and they started to clap, and they stopped. I thought, ‘Why did they do that?”

“I remember the first time I saw the film complete with an audience. Believe it or not, the most striking thing was how fine the detail had to be to get something across. If you didn’t pay attention to the smallest detail, then the cumulative effect of the film wasn’t going to play out. There’s a very stark example. At the end of the first chase, at the end of the storm… the film really basically builds to that and it ends act one. There’s a flare, we go to black, and then basically we see Max covered in sand, and the new act begins. Now, I remember thinking, ‘Boy, if this film works, there should be a catharsis at the end of that, just welcoming the silence. And if we’re lucky, they might even clap.’

“I remember watching the film with the audience, and they were leaning into the movie. They seemed to be really caught up and following it. I mean, it’s a visual music, and they’re there following the concerto and the symphony. And we fade to black, and they started to clap, and they stopped. I thought, ‘Why did they do that?’ I couldn’t work it out until I realized what we’d left was a little sustained note. We didn’t go to complete silence, and it sustained across into the next scene. When the audience heard that, it was a cue for them that, ‘No, this is not over yet.’ So it was very, very simple. We just faded out to complete silence. Then the next screening we saw there was a very satisfying clap from the audience; they were basically allowed to clap simply because everything went silent after all this noise and fire and all the fury of what it followed. So that was the thing I remember most apart from the fact that people seemed to be really engaged, and we scored well, and all that sort of stuff.”

Miller, Theron, and Nicholas Hoult attend the world premiere at the 68th Cannes Film Festival in 2015. (Photo by Stephane Cardinale/Corbis via Getty Images)

“The way I like to measure the worth of the film is for how long does it follow you out of the cinema?”

“I really don’t believe you know what your film is until a long time after it’s released. For instance, the first public screening was at the Cannes Film Festival. It wasn’t opening night, I think it was the second night, and there was rousing applause and a standing ovation that went on for a long time. But that’s a unique situation, because having been on the jury of the Cannes Film Festival, that’s a very enthusiastic audience. It’s almost as if, if you don’t get a rousing reception if the film was well made, somehow it’s a negative. So that was a false reading.

“The most accurate reading for me is to go to a full cinema, and pay for your ticket, and sit there in the audience and see it. It’s simply in a neutral way, in the way that people would turn up to see a movie, and that’s the most accurate reading. I guess the way I like to measure the worth of the film is for how long does it follow you out of the cinema? If you’ve forgotten it by the time you’re in the car park, then perhaps it’s not such a good movie. But if it stays with you for a long time and washes over you, then that’s really great. The greatest films are the ones that stay with you for a lifetime. I mean, we’ve all had films in our lives that we remember, whether from childhood, or at any time of our life, that somehow we can’t forget. They become part almost of our own individual narrative, and the great films seem to do that.”

“He opened his shirt, and there on his chest he had tattooed the Immortan’s branding. I thought, ‘Oh, God, he wasn’t just being polite.'”

“I was in Japan doing some promotion on Fury Road, and there was a Japanese critic, English-speaking, who was just so insightful about the movie. He read all the things that I hoped were there, that we thought were there, but were never sure whether people could pick up on. I said, ‘How many times did you see the movie?’ He said, ‘Once.’ I said, ‘You got all that from just on one reading of the movie?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ When the interview finished, he called me over to the side and he said, ‘Can I show you something?’ He opened his shirt, and there on his chest he had tattooed the Immortan’s branding. I thought, ‘Oh, God, he wasn’t just being polite. This movie did have a serious effect on him.’ He said, ‘It just encapsulated so much about who we are as human beings now and in the past.’ I thought, ‘Oh, God, gee, well, that’s about the best compliment I could get.’ Not to say that people should get tattoos [of the film], but that was a very, very, very moving moment for me. He read the movie so well.”

There are three more films set in the Mad Max world in the works. (Photo by Jasin Boland/©Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection)

“Mad Max: Fury Road is a very dark look at the world, but ultimately it’s a great forge on which to test humanity.”

“I didn’t expect Fury Road, particularly during the make of it, to be so well received. It was a tough film to make. But more than that, I didn’t think that there could be an action movie that would seem to have a lot of subtext, a lot of, as I say, iceberg under the tip. I realize now, that probably is why the film did have a resonance that people refer to. And I know that because I’ve had two people come to me and say, ‘Oh, I’ve just had a newborn baby girl, and I’m going to name her Furiosa.’ It’s a humbling thing, because it says that you have a big responsibility as a storyteller. You can’t be casual about your stories. They’re narratives that become part of people’s lives, or references to them. And we all have those.

“I mean, Mad Max: Fury Road is a very, very dark look at the world, but ultimately it’s a great forge on which to test humanity. In other words, in our world, in, say, the more comfortable first world, the unusual events are the darker, more malevolent behaviors of individuals. In the world of Mad Max, the positive regard for other people, acts of kindness, or the giving of oneself, are the exceptions. They shine like light in the darkness. Not wanting to get too cliché, but they become the exception, and therefore we learn a little bit more about that. So when Nux, the warrior, finally gets to do the one thing he’s wanted to do all his life and drive the rig and realizes that he has to crash that rig at the end, well, that’s a heroic act. When Max, the blood bag, wanting more than anything to be free, actually gives his blood to the dying Furiosa, that’s an act in which he relinquishes self-interest. It’s a heroic act.”

Mad Max: Fury Road was released May 15, 2015. Buy or rent it at FandangoNOW.