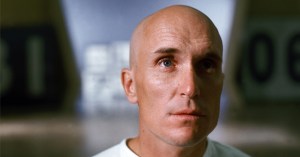

How Oscar Winner Brendan Fraser Became Charlie in The Whale

Fraser breaks down his transformation, from the authenticity of the physical prosthetics to his mental preparation for the role.

Writer-director Darren Aronofsky has never been one to shy away from uncomfortable subjects, and his latest film, The Whale, is no different. The film, based on a stage play of the same name, stars Brendan Fraser as a housebound English professor named Charlie who is affected by obesity. He begins the film in a downward spiral both physically and emotionally but attempts to reconnect with his estranged daughter before it’s too late. Fraser takes center stage in his first leading role in several years, and his performance has earned him some of the highest praise of his career; including a Best Leading Actor Oscar at the 95th Academy Awards. Ahead of the film’s release, Fraser sat down with Rotten Tomatoes to explore how he transformed into Charlie, from the authenticity of the physical prosthetics to his mental preparation for the role. He describes how he jumped on the opportunity to work with Aronofsky, explains how his talented co-stars helped bring the film to a new level, and recalls what it felt like to inhabit the role of Charlie.

Brendan Fraser: Hi, I’m Brendan Fraser, and this is how I became Charlie.

Word went out that Darren Aronofsky wanted to make a movie. I met Darren. He didn’t know if or not he was going to, or could make the whale because he needed to find an actor to hit the park. He had already conducted a pretty exhaustive 10-year search. The project had gone through three, maybe four different sets of producers, and he was producing at one point directors, but that was because of the challenge of creating Charlie. Darren was going to create Charlie using tried-and-true makeup, costume, and wardrobe. Adrien Morot is the creator and makeup artist. Charlie is a man who lives with obesity. His body is hundreds and hundreds of pounds, and to play the part meant that all the apparatus, all of the makeup, all of the applications, had to be as authentic and true to the human experience of living with obesity, or as near as possible as to get to that reality. So processes of digital scanning, printing molds, keeping consistency in the applications, all had been mandated to have the obeyance of gravity and physics.

This was not going to be a repeat of what we’d seen in movies for years, and I watched a lot of them. If ever there was an actor or actress in a weight-gain costume, we paid attention to it. And one thing that was consistent about, whatever the intentions were, whether it was a pejorative joke or an unfair mean statement about a character creating them to inhabit that body, we were not gonna do that. We firmly believed that the audience will buy into the reality of who this is, as long as the actor does, as long as the makeup and the look are authentic. And as long as you don’t notice where the seams are, there was no CGI treatment. Well, that’s not true. There was maybe there’s a little cure put on. Maybe the fabric acted up a little on one morning, was in his own movie but, you know, we’d smooth that out, so it didn’t take your eye away from that neurology that we all share that can pick out the details of what’s false and what isn’t. I mean, that’s part of the magic of movies anyway. But all of that technology and, and all of that support went into creating Charlie, who is at essence, he’s a man, he’s a father, he’s a teacher. He is a lover. He’s well-read. He is infinitely human. He’s flawed.

Charlie’s a man who lives with certain regrets for his actions. He fell in love, and it wasn’t a decision that he made. He was a married man with a child who fell in love with a man. He tragically left that relationship with the mother and his daughter to pursue that relationship. As fraught as that was, those are the life choices that he made. And when we meet him, we’re seeing what the fallout with the consequences are of that life choice. You know, whatever you think about that doesn’t matter because this is the reality of who he is. He’s in, in his own way, true to himself. But because he weighs hundreds and hundreds of pounds, and his health is as compromised as it is, he realizes all at once everything he’s been pushing aside about not getting medical assistance, by not changing his eating habits, all of that comes to a head when he finally realizes he has mere days to live. And he laments that he has not made it right with his daughter. And the salvation that he aspires to can only be attained if he’s able to apologize to her in a meaningful way, if that is even possible. And that’s the obstacle. And, you know, there’s no villain in this film. Really.

Sadie [Sink] has a prescient, remarkable ability as an actress, and I had a front-row seat to watch this young woman come of age, and we’re going to be seeing clearly a lot more of her as what we should. She’s, she’s that scary talented. I believe that with all my being, all my heart, she could have fallen into the trope of playing an angsty teenager, a rebellious young person who is out to set the world on fire, but at heart, she’s a very hurt, sad little girl still. And that manifests in her focused rage that she has for her father. And the facility that Sadie has with playing that is eye-opening and remarkable. Hong Chau, again, firmly established in her professional life and with obvious good reason. She has an innate ability that I saw to make everything that she does as a character, authentic, I mean, believable.

Even more so in between the lines. She can say more in the silences and the pauses than what you’re given as an actor to speak as dialogue. I think it was a film that was made during the time of Covid, um, when we all felt clearly under existential threat in our own way, and strangely, for what it’s worth, it somehow brought us all closer together, which is important in telling a story that’s a chamber piece, really. An adapted screenplay from a stage play by the writer himself to maintain that intimacy of five people in search of salvation. And we don’t know if they’re going to get it until the last gasp.

I became accustomed to Charlie’s costume and body pretty quickly. And when I wasn’t wearing it, I would feel almost an undulating sense of kind of a quasi vertigo or something. I don’t know what it was, but I think it was a signal to my body that a body that carries the weight that that does requires you to be strong in ways that you’re not ready for. And it gave me more profound respect for people who do live with obesity. The realization that I had in playing the role was not because of anything that I was wearing or was, uh, uh, encumbered by. That was all helpful to tell the story. I think it just came from seeing the final film alone in a screening room months and months and months after we’d finished, and feeling like I was watching something that I intellectually knew about, but I was seeing a completely different character. But still being able to recognize, I guess, myself in that as much as I wanted to lose myself in, in the role, I think I realized that you need to forget everything that surrounds it and just play the part as a man, as a person.

Charlie’s great white whale is his redemption, his need to reconnect with his daughter. And we don’t know if he’s gonna succeed or not. He doesn’t know if he’s gonna succeed or not. We all have our whale that we’re striving to get just the same way as in Moby Dick. The literary references are important, even so in the title. It’s a litmus test of sorts for the beliefs that we may hold about people who live with obesity in the sense that it’s not a pejorative joke. It’s not. It’s a literary reference, and a noble one at the same time. And again, he is an English teacher, he’s an educator. He teaches his kids, his students, with the camera turned off because he wants to preserve them from his own sense of shame, which is really moving to me, which is really sad for him. But he implores them to do and say something honest, be authentic. But he can’t get that from them until he shares himself with them as he is.

First and foremost, he’s a person, he’s a human being. We’re all human being. And this is a movie that can, in my firm opinion, we can change the culture surrounding how we describe or refer to people who live with obesity. Let’s call it what it is. It’s prejudice, it’s bigotry. It is the last domain of accepted casual prejudice in how we describe and speak of the issue and the people who live with it. That’s unfair. And I believe that by showing an audience those views that they may abide, participate in, or ignore. I challenge you to not reorient the way that you thought about that by stories, and I hope we can change hearts and minds. And even more so for having had worked with the Obesity Action Coalition, this is a support group of tens and thousands of people strong, providing counseling with regard to eating disorders, mental health issues, medical referrals for bariatric procedures. I spoke to probably 10 or 15 people who gave me their story, vulnerably told me about everything from when they were very small and were spoken to sadly vindictively, and how that affected their sense of confidence in how they grew into being adults and finding them in a place where they’re bedridden. And their very life depends on if or not they can change the disease of obesity in their life, maybe with a procedure, or changing their habits. It doesn’t matter. The point is that they told me that this is a movie that could save someone’s life.

Charlie never eats for pleasure. Charlie eats to sadly harm himself. He is the manifestation of trauma. That what he puts into his body for all that harm that he has endured all his life, he’s been derided. It’s manifest on who he is as a human being, that’s a lot of pain for this man. His relationship to food at this point, it’s fraught. It is not for pleasure, challenging is the word. It’s not gonna be easy to watch certain sequences in this movie, but there’s nothing gratuitous. But it is important that there is authenticity and honesty about who he is, and how he came to the place where he is now before his time runs out.

The Whale is in theaters, and available to rent/buy digitally.