Richard Curtis has a plan. “What I’ve decided is to choose recent films,” he explains to RT. “I do think that often people get stuck in always picking the five greatest films of all time, films they saw between the ages of 17 and 22, because that’s when you’re forming your opinions. I think I’ll talk about modern films, which aren’t necessarily the greatest films ever made, but are five great films.”

Modern films are certainly Curtis’ bread-and-butter. Best known for defining a genre with Four Weddings and a Funeral, the writer of Notting Hill and Bridget Jones’s Diary turned to feature directing in 2003 with Love, Actually — an entire career on the big-screen set in the here and now. The Boat that Rocked, out on DVD and Blu-ray in the UK this week and soon to hit US cinemas retitled Pirate Radio, is his first ‘period’ film and he doesn’t go much further back in time than the swinging 60s.

On the small-screen, he’s Britain’s ruling king of comedy, giving us the ultimate history lesson through the various series of Blackadder, and defining comedy for the 80s and 90s through BBC favourites Mr. Bean, The Vicar of Dibley and Spitting Image. In 1985 he founded Comic Relief, which has raised £80m for good causes this year alone.

Read on to learn about the five films he can’t do without.

“That will be the only horror movie on any list of mine. The first time I saw The Exorcist, I had to sleep with the lights on for about four years, so horror is not for me.”

There are so many other funny things — when Kristen Wiig is rude to Katherine Heigl when she gets her job, and she’s going on about how lucky she is to get the job, it’s completely hilarious. Both Seth Rogen and Katherine are so charming and funny, and it’s so modern, on the edge and hard; a real romantic film. I think that if romantic comedies are meant to be romantic and funny, then that’s a perfect example. It’s very relaxed and at ease with itself, and doesn’t try too hard, or doesn’t seem to be trying very hard, and I think that’s very much to do with how Judd makes his movies. I’m sure he knows exactly what he wants, but it does have a slightly improvisational edge to it, because he does work with people that he knows very well, so there’s a naturalness to it, and I think it’s a great modern film. I haven’t seen Funny People yet, but I have very high hopes for it, I’m looking forward to it a great deal. “

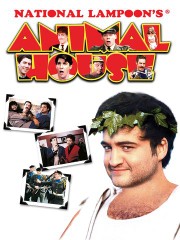

“It seems to me like a really great, classic, funny character movie hiding in wolves clothing, pretending to be a big stupid old generic college movie, but it actually invented the genre, and I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a funnier version of those movies. Certainly when I was doing The Boat That Rocked, it was M*A*S*H on the one hand – very casual, conversational, just guys doing a weird job – and Animal House on the other – with big characterisations and set-pieces.. So we’ve got four moderns and one slightly older. Can I have one more? Am I allowed? Just for sorrow?”

I think we can let you have another film.

Richard Curtis: OK – The Son’s Room by Nanni Moretti. He was this kind of comedian when younger, and was always called Italy’s Woody Allen, and in a way he’s fulfilled that promise, because Woody Allen also made some very profound films. The Son’s Room is an amazingly gentle, completely sorrowful movie, which I don’t even know whether or not to recommend. It’s full of sadness but everyone who is thinking of having a family should see the film so that they know the risk, and everyone who has got a family should see the film so that they understand how in the middle of the most normal conversational world, sorrow can hit you. But it’s got the best music of any film I’ve seen and it’s got this Brian Eno track at the end. The movie can’t be resolved because it’s about grief that never ends, but somehow the music acts as some way back to normality. So I think The Son’s Room is the film I’ve been most struck by in a way, over the last ten years, the most truthful film I’ve seen.

Music in a film is obviously very important to you…

RC: Yeah, I don’t know. Strangely I watched The Godfather the other day, and the Godfather Soundtrack is extraordinary, it never stops. It’s either jazz music or orchestral music or exciting music, he never lets it go, and that’s the way he keeps the pace up. So I always wanted The Boat That Rocked to be an ecstatic movie. I remember at the end of Bridget Jones, the second one, where we were trying to choose which of the three songs to put at the end where she’s running after Colin Firth – in the end I just said, “Put them all in. Put all three. Let’s have Beyonce, let’s have The Shirelles, and let’s have Barry White.” So I like the idea of going for it, wall-to-wall. And in a way I’ve always thought of my films as being like a Madness album or like an ABBA album, full of delightful little scenarios and very high spirited bursts of things.

But as a writer, just as sort of autobiographically, I listen to music all the time while I’m writing. It always cheers me up and always lifts my spirits, and it always has. On The Boat That Rocked I just wanted to make a film about that feeling of what it’s like to be exhilirated day and night by pop music.

Does the music that you’re listening to end up in the movie when you’re writing?

RC: Yes, but the weird thing is when the music doesn’t. I wrote the whole of Love, Actually listening to one song, which is The Loving by XTC, which is a huge orchestral song about everyone in the world being full of love, but I didn’t put it in the film. Notting Hill was based around two songs, one of which was Wasting Time by Ron Sexsmith, and the other – very oddly I used to listen to it all the time because it exactly represented the pitch of the emotion I wanted in the film – was a version of Downtown Train by Everything But the Girl. That was what I wanted the film to feel like. I used that as the pattern and then threw it away, because there wasn’t actually a place for it in the film. But I often get the mood of what I’m writing from pop music.

Did you have any problems with rights for any of the songs you wanted to use in The Boat That Rocked?

RC: No. With The Boat That Rocked, we had a bit more money, so we got most of what we wanted. Some songs you just couldn’t get because they wanted something like a million pounds – those were the acts who just didn’t want their songs in movies. When Hugh Grant dances in Love, Actually, we wanted a Michael Jackson song we couldn’t get, because it was about a million pounds to use.

But on the whole, these days, I get what I want. My bad memories of The Tall Guy, the very first film I made, are thankfully in the past. It was meant to be structured around three songs by Madness. It was meant to start with Yesterday’s Men, go to The Sun and the Rain, then end with It Must Be Love, and that was the shape of the movie. But they could only afford one song, so we only had It Must Be Love, which was a great disappointment.

There’s a very funny bit in that movie where Jeff Goldblum sits down and listens to a radio and he’s heartbroken. He switches it and on comes a really sad song like Let the Heartaches Begin, so he switches it again and on comes another one called So Sad or Cry in the Rain or something, but if you listen carefully, they’re all sung by my friend Philip, because we couldn’t afford any of the songs. We had to spend an hour in a studio to do one impression of Long John Baldry and one of the Everly Brothers. So in the old days we couldn’t get what we wanted, but now it’s easier.

The Boat that Rocked might be the first film I’ve seen with a double-CD soundtrack.

RC: And I don’t think that’s all of them either – we’ve had to leave out one or two songs from the middle of the movie that haven’t made it onto the soundtrack. But yeah, it was very passionate. What you realise when you’re making a film like that is that people do love their pop music, and as people are finding out now at festivals, living with pop is a great way of leading your life. When we made the movie, everyday when we went out on the boat, all 140 of us, and they blared pop music for an hour. The moment it was lunch we would put it on over the huge speakers, and on the way home we put in on the speakers, and it was an idyllic life.

And you were working with Bill Nighy, who we know is a huge music fan – that would have been fun…

RC: Yeah, Bill loves his pop music. He’s obsessed, at the moment, with a guy called Maxwell, who he says is a great genius, and has just had a huge hit in America. What was nice was that there was one or two songs that I picked that nobody had heard of, like Crimson and Clover by Tommy James and the Shondells and All Over the World by Francoise Hardy. Everybody had one or two things they were absolutely delighted to meet in the film. And that was my aim, to have a mixture of very high-profile songs and songs that people didn’t know as well.

What’s next for you as a director?

RC: I’m doing a huge range of things, but I think my next movie is probably going to be a film about time travel, but it’ll be quite complicated so it’ll take a while to work out.

Lots of paradoxes to figure out?

RC: I’m not going to worry about things like that, but there are always going to be issues!