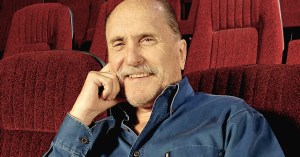

Director Tomas Alfredson on Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

The director of Let the Right One In talks about his latest film, the slow-burn espionage thriller starring Gary Oldman as John le Carré's iconic spy.

Though he’s been directing films in his home country since the early ’90s, Sweden’s Tomas Alfredson came to the attention of mainstream genre audiences with 2008’s Let the Right One In, an exquisitely pitched coming-of-age horror piece that also happened to be one of the finest films of the decade. For his follow-up, Alfredson has — somewhat curiously — directed an adaptation of John le Carré’s classic espionage novel Tinker Tailor Solder Spy, about a retired British operative (Gary Oldman) called back into the clandestine world of MI6 to flush out a Soviet double-agent. Like his previous film, Alfredson’s latest is another chilling evocation of period — this time an oppressively drab London in 1973 — and features a performance by Oldman so meticulously insular it’s quite unlike anything the actor’s done before. We spoke to Alfredson recently about the film.

How did you arrive at Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy? I’m guessing you would have been offered a lot of horror films after the success of Let the Right One In.

Tomas Alfredson: Yes — and I can’t blame people for that, because they don’t know about my previous work. It was a little strange, the situation, because I’ve been directing films and stage plays and television for 20 years before that, and suddenly to experience this change quite late in my career was confusing — and I wasn’t sure if that was a dream come true. I didn’t know, really, in what direction to turn. So I decided to work with theater for a while, and do something else. The making of Let the Right One In was very demanding, and in many ways very unhappy, because back home it was a film that nobody would touch when it was finalized. The distributor wasn’t interested; the theater owners didn’t believe in it; the financiers disappeared. It was sort of put away in a cupboard for 10 months, so it was like… I thought I did a flop. And I loved it; I had invested so much time and love into it, so I was so disappointed about that. And then it started — before it actually opened in Sweden — it was shown in festivals here and there, and the success story of it started.

So I was very confused by that. I read hundreds of scripts [afterwards], but they didn’t really interest me. Then one day, this. I think it was my manager that heard that Working Title, the production company, had retrieved the rights to Tinker Tailor and, oh, I remember those gray men [laughs] from the TV series from the ’70s — I thought, “Yeah, that sounds interesting.” And I met with them, and Mr. le Carré himself, and I think that those meetings made me want to do it — and the material, of course.

Is it true that John le Carré saw Let the Right One In and said “Hire this guy”?

Maybe! I have to ask. John le Carré is a very open-minded person, and he’s very updated. I don’t know any 80-year-old guy who is so updated with everything. He reads everything. He’s informed. He has the telephone number to anyone. And he sees everything that’s presented in theaters and on television. But I haven’t asked him.

There’s a similarity to the secretive, almost suffocating worlds of the main characters in Let the Right One In and Tinker Tailor — is that a dimension of stories that appeals to you?

I think it’s people who look differently on the outside to how they look on the inside — that’s what interests me; and I think, maybe, that is a description of myself in many ways. It’s quite hard to describe why you want to do something. It’s just something that happens. The less you know about those things the better, I think; you can peek into that too much, your inner mechanisms. I think filmmaking is 95 per cent exactly the same for any filmmaker — it’s that last five per cent that you shouldn’t investigate too much.

What’s your personal relationship to this British espionage world? You were growing up in Sweden at the time the movie is set. What are your memories of the Cold War?

Well the espionage world I don’t know anything about, except the things you’ve seen on TV, but we were very close to the Cold War and we lived even closer to the Iron Curtain. Sweden was a very strange mixture of this social democratic rule and old feudal monarchy, so there are a lot of cultural connections to the British in many ways, in what kind of history we had in the feudal system — which is very unmodern, but still, it’s there. On television there were two state-controlled channels and sometimes there was some import from England or the US. From America it was something tinsel, in color and very glittery, promising a lot; and then there would be something gray, and brown, from the BBC. [Laughs]

You seem to have a gift for capturing the essence of time periods without drawing attention to them. What’s the trick? Not emphasizing very obvious period details?

Yes. It’s like, it’s too easy to put sideburns on everyone and play hit records, you know — all those cheap ways into the hearts of people. I think the period was so much about, not ’73, as this is set in, it’s about the ’60s and ’50s and ’40s — all the periods before that. Because if you would visit someone in a home in 1973 there would be one chair that was bought last year and the rest would be stuff from the ’40s or the ’50s. Too often people always sort of push the volume to 10 when they’re doing period stuff. But, it’s of course a lot of fun to do it, and revisit — especially if you have experienced it yourself. I have very clear memories myself. I visited London for the first time when I was seven or eight, in exactly those years.

And it looked that dreary, huh?

Yeah. [Laughs] I think so.

There’s quite a distinctive shot in the film with graffiti on a wall reading “The Future is Female,” which stood out for me in the context of the movie. Was it a reference to anything?

Yeah, it was Maria [Djurkovic], the production designer, who’s a fantastic person and a fantastic designer. We had this big wall down there and we wanted to do something with it, and she made some graffiti. [Laughs] I thought the line was beautiful; a very nice statement. I know that the art department people were quarreling about it.

Really? It was great because the film is so entrenched in this hermetic, masculine world and then all of the sudden there’s this weird flash of lighting from the future.

Yes! I love it. I thought it was brilliant. [Laughs]

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy opens in limited release this week, and expands wider next week. Look for our interview with Gary Oldman next week.