13 Pacific Islander Movies that Showcase the Richness and Diversity of Pasifika Cinema

Pacific Islander writers, musicians, curators, and commentators share their picks from the vast and diverse world of Pasifika cinema and tell us why the movies mean so much to them.

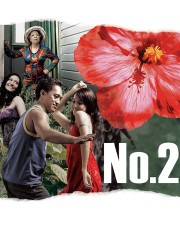

(Photo by Matt Grace & Daryl Ward/©Paladin Films/Courtesy Everett Collection)

As part of AAPI Heritage month, we asked five writers, musicians, and film experts to share the Pacific Islander films they love. Below are their selections and why they mean so much to them, beginning with a reflection from TV writer, journalist, and author Maria Lewis.

“We are the original storytellers,” Taika Waititi said as he closed out his Oscars acceptance speech when he won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay in 2020 for Jojo Rabbit. Waititi famously – and by his own admission – talks a lot of s–t. Yet of all the s–t he has talked over the past two decades of his career, this was the most important. Why? Because on arguably Hollywood’s night of nights, up there on a global platform, a man of mixed Māori and Jewish heritage reminded everyone that, for “Pacific Islanders” specifically, telling stories is not just something we do, it’s an integral part of who we are, what we are, and where we come from.

It’s currently AAPI – Asian American Pacific Islander – Heritage Month, which is an insanely large acronym to try and group two hugely diverse and complicated ethnicities under, but hey, it’s either this or not being acknowledged you exist… The Pacific Islander term is loaded with a complicated colonial history that is probably best broken down by Kristian Fanene Schmidt in a recent Instagram video. (Kristian’s choices can be found below, too.) For those of you playing at home, essentially it’s meant to refer to every brown person living on any one of the thousands of islands that span from Palau to Easter Island.

(Photo by Anita Narbey)

It’s a lot of geographical space, it’s a lot of different cultures and beliefs and languages and mythologies and history, and it’s a lot of stories to cram under one “Pacific Islander” tag. Which is why the best way to celebrate the many cinematic accomplishments of such a beautiful and broad expanse of people is not to ask one person, but many, to reflect on the movies that mean the most to them – for each to talk to stories they have connected with and have celebrated, informed by their specific lived cultural experience. Which is what we have done here.

As a woman of mixed descent growing up in Australasia, the films that have shaped me, defined me, lured me, are extremely personal and they are not universal, just as “Pacific Islanders” are not universal. They’re films like 2010’s Boy, now one of the lesser-known Waititi joints but a breakthrough at the time for its equal-parts hilarious and heartbreaking portrayal of absentee fathers. They’re films like 1994’s Once Were Warriors, a brutal yet important film not just for the telling of largely untold domestic stories and residual Colonial trauma, but the ripples of opportunity that the film created for talent like Temuera Morrison, a now veteran character actor and vital part of the Star Wars universe, and director Lee Tamahori, the first person of color to direct a film with a budget over $100 million in Bond movie Die Another Day.

They’re films like Whale Rider, which brought the work of one of New Zealand’s great novelists, Witi Ihimaera, to the big screen and gave us a still bafflingly great performance from Keisha Castle-Hughes, who became one of the youngest Academy Award nominees for Best Actress when she was just 13 years old. She remains only the second Polynesian actress to be nominated for an acting Academy Award, following Jocelyne LaGarde in her first and only acting role in 1966’s Hawaii. They’re films like Moana, which put an amalgamation of “Pacific Islander” culture on the world stage and gave a generation of children dolls and merchandise and characters that looked like them. For all its imperfect ambition, a glossy Disney animated feature being translated into language is invaluable for the culture now and in the future.

(Photo by © Magnolia Pictures)

They’re films that have slipped under the radar for many, like Toa Fraser’s heart-racing The Dead Lands, from 2014, which is best described as a Māori Apocalypto and saw its own television adaptation on Shudder just last year. It’s Born To Dance, which in 2015 spotlighted the skill and significance of movement to the culture with the work of Parris Goebel, Tia Maipi, and countless others. It’s even Training Day, maybe weirdly, but for the scene-stealing performance of Cliff Curtis as Hillside Trece gang leader Smiley and what that enabled him to do for the next 20 years as a stealthy Polynesian star in Hollywood and as a producer helping shepherd the next generation of stories like The Dark Horse. It’s the work of Chelsea Winstanely, top to bottom, the first Indigenous woman ever nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award for her work on Jojo Rabbit and her tireless efforts as a storyteller to make sure that those who came before – like Merata Mita – are featured in their own stories, such as the 2018 documentary Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen.

It’s the Jemaine Clement of it all, infiltrating Hollywood with Flight Of The Conchords, then crafting a very weird and specific legacy with his skills as a musician, as a producer, and as an entirely unpredictable performer who elevates everything he’s in: whether that’s Legion or Men In Black 3. (I said what I said). It’s the award-winning short films by women and about women, like Purea and Hinekura; it’s the rom-coms like Sione’s Wedding; it’s the documentaries like Poi E: The Story of a Song and Dawn Raid that spotlight the impact of our music.

It’s endless and infinite, which is why it’s crucial to iceberg this: skim the surface and then plunge deeper based on the suggestions and cinema recommended. Because “Pacific Islander” identity is not one thing, as the career of Dwayne Johnson demonstrates. Hollywood has long struggled to understand what to do with us, but The Rock cemented (sorry) a future where one day an Indigenous kid won’t have to be grateful for the slightest crumb of representation (looking at 13-year-old me, getting pumped over Skinny Pete in The Italian Job remake). They can be a global wrestling superstar, they can be a businessman and a business, man, they can be the franchise savior, they can be the biggest star on the planet, and they can do it all while being proudly one of the “original storytellers.”—Maria Lewis is a best-selling author, screenwriter and film curator

13 Pacific Islander Movies that Showcase the Richness and Diversity of Pasifika Cinema

Meet the Contributors:

Maria Lewis is an author, journalist, screenwriter, and film curator based in Australia. She is the author of seven novels, all part of the Supernatural Sisters series, and a film curator at Australia’s national museum of screen culture.

Sonja Hammer is a diaspora First Nations (Ngati Kahungunu, Kuki Airani-Aitutaki ) woman originally from Aotearoa/NZ, identifying as Takataapui and is Takiwatanga (Autism spectrum). A broadcaster, festival programmer, and advocate, she is the co-founder of the first Australian LGBTQIA+ pop culture organization Queer Geeks of Oz and Secretary and Creative Arts Ambassador for not-for-profit Pasifika organization Pacifique X.

Tahlea Aualiitia is a journalist with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). She is currently working on the Pacific Beat program as a presenter, producer, and reporter. Tahlea is very proud of her Samoan/Italian heritage.

Kristian Fanene Schmidt was born and raised in Porirua, Aotearoa/New Zealand while both his parents hail from Samoa. He has an academic background in Pacific Studies, Law, and Education, and was a VJ with MTV Australia before relocating to Los Angeles where he now writes for various publications including The Root, Color Bloq, and for the Sundance Institute.

Hau Latukefu – also known as MC Hau – is a hip hop artist, best known for his work in the group Koolism, and an MC and radio presenter who currently hosts the Hip Hop Show on Australian station Triple J.

Thumbnail image: Anita Narbey, Paladin Films, Magnolia Pictures