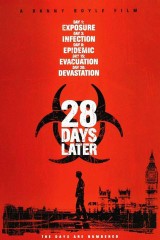

21 Most Memorable Movie Moments: “Hello?” from 28 Days Later (2003)

Director Danny Boyle on shooting London's loneliest landmarks, and resurrecting zombies for a new century.

Watch: Danny Boyle on the making of 28 Days Later… above.

In 2019, Rotten Tomatoes turns 21, and to mark the occasion we’re celebrating the 21 Most Memorable Moments from the movies over the last 21 years. In this special video series, we speak to the actors and filmmakers who made those moments happen, revealing behind-the-scenes details of how they came to be and diving deep into why they’ve stuck with us for so long. Once we’ve announced all 21, it will be up to you, the fans, to vote for which is the most memorable moment of all. In this episode of our ‘21 Most Memorable Moments’ series, director Danny Boyle recalls shooting London’s loneliest landmarks and resurrecting zombies for a new century.

VOTE FOR THIS MOMENT IN OUR 21 MOST MEMORABLE MOVIE MOMENTS POLL

The Movie:

28 Days Later, directed by Danny Boyle from an Alex Garland script about humans mutated into speedy zombies by virus infection, was an inflection point for horror movies. The underground hit made over $80 million worldwide, and signaled a shift away from post-Scream teen slashers of the late ’90s and earl 2000s, and showed studios that audiences all over have were seeking horror flicks that bit harder. The film was shot with digital cameras, just above consumer-level grade, giving survivor Jim (Cillian Murphy) and his journey across a newly deserted England a rush of post-apocalyptic immediacy. This was when shooting on film was still the norm, so grimy, tethered footage felt like a glimpse into a new world. And it was a horrific, and horrifically effective world that Boyle created.

Danny Boyle on the set of 28 Days Later. (Photo by © Twentieth Century Fox)

“We made this film about social rage.”

“We had this idea that the film is shot by somebody finding a camera in the debris that’s littered, because everybody’s gone. The s–t that’s left behind would be these consumer cameras, which were everywhere at the time. They’ve been replaced by phones now. We made this film about what we called, at the time, social rage. A big thing was road rage, this kind of intolerance, particularly in cities, of each other. People attacking people in other cars because somebody had cut them off in traffic. And the social intolerances of your fellow citizen, felt like it was almost in crisis proportions. And then 9/11 happened.”

“People changed the film and made it about how vulnerable cities were.”

“I think what happened is that because we were one of the first films to come out after 9/11, people changed the film and made it about how vulnerable cities were. Previously, cities felt massive and growing and powerful and invincible and answerable to no one. It was prosperous, and people were confident. Suddenly, cities felt incredibly vulnerable. [That’s why 28 Days Later‘s] emptiness of London, of the London streets, caught on as an image. Like New York or San Francisco or Tokyo, famous sites, emptied of people. They felt delicate, like they’d lost.”

Murphy as Jim, waking to a new empty world. (Photo by © Twentieth Century Fox)

The Moment: “Hello?!”

After a brutal opening that sees environmental extremists letting loose rage-virus–infected chimps on the populace, Boyle allows the film to simmer as hero Jim awakens in the hospital after a road accident. In his teal medical gown, Jim wanders the smashed corridors left in disarray, wired telephones swaying against the walls, and then out into the startlingly de-populated London metropolis. The first empty landmark Jim traverses is the Westminster Bridge, which has become 28 Days Later‘s signature shot, probably also due to the fact you get Parliament palace clearly in the background. Then Jim yells into the air that simple and powerful word which connects people across different languages, now rendered deaf and empty: “Hello?!”

Students stopped traffic so that Boyle could capture Murphy in an empty-looking London. (Photo by 20th Century Fox Film Corp.)

“We hired a lot of students, because they’re cheap, to be our traffic marshals.”

“We were going to call this film at one point, Hello. But it sends the complete wrong signal. [Laughing.] One of the technical advantages of using these smaller cameras is that you could shoot a location, not multiple times, but you could shoot it from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Cillian was in no rush, he could just walk across. But you don’t get much time at these locations free of people even at four o’clock in the morning when we shot. So what happened was we hired a lot of students, because they’re cheap, to be our traffic marshals.”

“It tends to be quite angry men driving around London at four in the morning.”

“My daughter – who was 18 I think – came along and she brought some of her friends and they’re quite glamorous girls. The sun was up and it was mid-summer and they’re all wearing short skirts or shorts. And it worked in our favor because – it’s very sexist to say it – but it tends to be quite angry men driving around London at four o’clock in the morning. So they were stopped. And it wasn’t me stopping them, to whom they would say ‘F–k you!’ and drive straight through. It was these lot of lovely girls, students who were saying, ‘Hey, hello. Good morning. We’re making a movie here. Do you mind waiting for two minutes?’ ‘No problem, darling. I’ll wait here. What’s your name?’ And so every day we hired more and more of these girls to block the traffic. And there’s not a moment of CG in it, where we took out vehicles or anything like that.”

The shot became the defining image of the film. (Photo by © Twentieth Century Fox)

“It’s become a poetic or artistic response to the 9/11 apocalypse.”

“[In the sequence, Jim visits Horse Guards Palace and the Duke of York steps, eventually arriving at Piccadilly Circus, a typically bustling commercial square.] The reason we went to Piccadilly Circus was there’s a statue there of Eros firing the arrow of love. There was scaffolding all around it. They were fixing it. We wanted all the monuments, all of the famous places to look perfect. It was just the fact that there were no people around that was wrong. So we came up with this idea. We had this lovely woman spend months making all these notices on these boards. ‘Have you seen this person?’ ‘I will wait here for you.’ We went there on the day, clipped the boards onto the scaffolding. Jim walks up there and realizes the older people have gone and before they’d gone, they’ve tried to find each other and they’ve gone too. They’ve all gone. And then, of course, 9/11 happened. People put notices trying to get hold of people, and it’s very moving. It’s actually a very moving thing that we do in a time of crisis. [Our Piccadilly solution] was a response to something that wasn’t ideal for, but became something that fueled our story more and more. In a way, it’s become a poetic or artistic response to the 9/11 apocalypse.”

The Impact: Zombies Ate My Movies!

28 Days Later demonstrated that not only was there going to be a future for digital, it was going to be the future. 28 Days Later‘s most famous sequence was cobbled together from different and hasty angles, something that would’ve been impossible with set-up heavy film cameras. This led the way for found footage horror to go mainstream (think Paranormal Activity, [rec], Chronicle), a necessary response to voyeurism in the age of internet and YouTube. How fitting a roundabout tribute to 28 Days Later then, that we describe popular videos like an unstoppable infection, as viral.

Within the world of horror, by the end of the ’80s, slashers and sequelitis had dragged the genre down into the creative doldrums. (The Sixth Sense, Scream, and The Blair Witch Project gave some late-decade sparks of life.) Zombies at the movies in particular had turned into a shuffling, shambling joke. But they lived on in another medium: Video games, especially the far-reaching Resident Evil series, which had inspired writer Garland. The success of 28 Days Later made zombies a hot monster ticket in film, with the Resident Evil movies, Shaun of the Dead, the Dawn of the Dead remake, and the return of genre grandmaster George A. Romero’s Land of the Dead following immediately.

Boyle’s movie rejuvenated the zombie genre. (Photo by © Twentieth Century Fox)

“Alex instinctively sensed that the genre was ready for a kind of reboot.”

“I didn’t do any research into zombie movies. I mean, I knew a few, like anybody who loves movies. Alex [Garland] was a real zombie fan…[and] rightly, instinctively sensed that the genre was ready for a kind of reboot. And I thought, ‘That’ll be good for me,’ and Alex to come at it from different perspectives like that. I didn’t feel I was making a genre film. So I came at it like that. He came at it like that. And that was a great combination… It’s been amazing since then, the way that The Walking Dead and other other movies have obviously taken advantage of that re-interest in the genre.”

28 Days Later… was released on June 27, 2003. Buy or rent it at FandangoNOW.