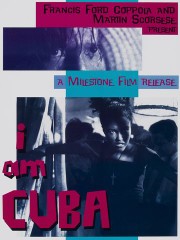

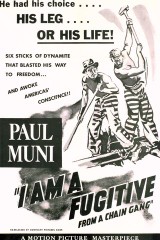

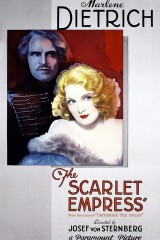

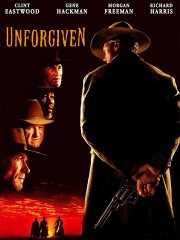

James Gray’s Five Favorite Films

The Ad Astra director expresses his love for Eastwood, Fellini, and pre-Code cinema.

(Photo by Pablo Cuadra/Getty Images)

James Gray has won the affection of international film critics with New Hollywood throwback offerings like Two Lovers, The Immigrant, and The Lost City of Z, but with Brad Pitt suited up for space in Ad Astra, Gray gets his first major studio project off the ground. Like many of Gray’s films, there is a family story at the heart of his Heart of Darkness-esque space movie, with Tommy Lee Jones playing Pitt’s astronaut father who’s been missing for 20 years but might have just made contact from Neptune. Pitt embarks on a mission not just to find his father, but also to stop the electrical surge from an outpost near the distant planet, which has caused thousands of deaths on Earth.

The film debuted at the Venice Film Festival with high accolades for its thrilling sequences, Pitt’s performance, and the astounding visual effects (which the Fox-Disney merger granted Gray a few more months to fine-tune). Ahead of Ad Astra’s nationwide release — it’s Certified Fresh at 81% on the Tomatometer — Gray told us his Five Favorite Films and spoke about the gestation of his current film. That his choices come from Russian, Austrian, and Italian filmmakers, in addition to Hollywood, should surprise no one familiar with his work as a filmmaker who’s keeping the ’70s maverick spirit alive in modern American cinema.

Brian Formo for Rotten Tomatoes: Something that’s constant through your work is family expectations and the suffocating weight of that. So I’m wondering, with Ad Astra, did you start with a father-son story in space, or did you want to make a movie in space and have these big set pieces, but then it became more natural to tether it to a father-son relationship?

An excellent question. I wish I could tell you that I came up with the story first, but it’s not how it happened. I was thinking very seriously about a childhood memory that I had. I grew up in New York, and you couldn’t see the stars. The sky had this kind of dull orange at night, because the city was so lit up. I remember there was a blackout that hit the city — this was 1977, in the summer of 1977 — and I remember, as all the lights went out, you could see the stars for the first time.

All of a sudden I had this weird memory back to that feeling — it was, like, 2011 and I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to make a movie about what is out there?” I talked about it a lot with my friend and co-writer, Ethan (Gross), and I asked, “What it means to be out there, and are there aliens, or are we alone?” Well, there are a lot of movies about aliens, and good aliens and bad aliens. (Steven) Spielberg’s done incredible work about that, but his movies, they play like fables. E.T. is like a fable; Close Encounters, like a fable. Beautiful, beautiful films. (Stanley) Kubrick made a beautiful film, of course (in 2001). The alien is a black slab of granite, whatever it appears to look like. Is that a good alien? A bad alien? What does that mean? You can project anything you want on it. So he beats the trap of false gods, you know?

(Photo by 20th Century Fox)

But we thought, “Well, what does it mean if you find that there’s really nothing out there? And if there’s nothing out there, that poses its own set of existential questions.” So it started from that, really, and that was the chain of events. Then I tried to start getting the story as personal as I could, and we wanted to steal from — as pretentious as this sounds — we wanted to steal from The Odyssey, and tell the story, really, from Telemachus’ point of view. His father, Odysseus, goes away for 20 years; he doesn’t know what happened to him. What that would mean, and that sense of abandonment that Telemachus must have…

Now, of course, Homer’s story ends very differently. But that’s where that came from, a kind of mythic idea. Then, of course, you start to personalize it, you start to include things in your own life, and before you know it, you’ve got this tiny little story about a father and a son against the huge canvas, where you’re going out there, it’s the vast infinite. That’s really how it formed.

So, the opening in the film, and I’m not a take-a-notepad-to-the-film person, mostly because High Fidelity scarred me for life…

Oh when his girlfriend clicks her pen throughout the movie to take notes?

Yes!

Ha, what a nice aside.

So I’m not sure if I got the two words correct, but the movie opens with something like, in the near future, there’s hope and fear about humanity’s future. In presenting the future, what is something that you discovered in your research that gives you hope about the future, and what is something that terrifies you?

It’s an easy question to answer. Easy. Hope: the mapping of the human genome, hospital cures for diseases, the specialized treatment of things like different kinds of cancer, that’s fantastic. And fear, I think, is obvious. The fear is climate change and the end of civilization, the civilized world.

If you look at Mars… By the way, the NASA people I’ve worked with on this film, who are great, their hair’s on fire. The f—ing world is ending and, I mean, I understand that it’s a slow burn, but it’s not that slow. In fact, the permafrost is going worse up there than we think, you know? Greenland, large sheets are melting faster than we think, or we thought — now we know. Already parts of New York are uninsurable.

And lots of Los Angeles, for fires.

Yeah. I’m extremely concerned. So, I think progress is a beautiful thing. I think that we’ll be able to do things that we couldn’t imagine in terms of human longevity. Maybe we’ll figure out what it means in the future, to maybe find an answer to not just longevity, but market economics, where five people don’t control all the wealth on the planet. That’s a problem.

If we could solve that, that would be great, but I have hope that we do, because the world moves in cycles, strange cycles. I feel like we’re itching for a new path forward on how to handle some of our problems. But climate change, that’s a tough one. That’s a tough one. There are things like taking CO² and making it into oxygen. Apparently, technologically, there are ways to do it, but it’s ridiculously expensive. But we’re going to have to do it. I don’t see any other way around it. I hope I’m completely wrong.

(Photo by )

[Note: Mild spoilers below]

We can get morose for the whole interview, but this movie has a lot of very fun, thrilling sequences.

I hope so.

Like the moon pirates, the underground lake, or even just the opening, falling from space, et cetera. The mayday call for help and where that goes…

All of that was supposed to be thematically relevant, more than narratively relevant. The idea that, basically, unexpected horror is around every turn when you’re that far away from Earth. So we felt that it had thematic unity, if not narrative unity. Anything earthbound, it’s not meant to live out there. It’s not meant to be there. That’s not our friend, it’s different to us. We felt that the mayday response was an important sequence. Do people want to know about that beforehand?

I loved the surprise, so I think, where we’re at for filmgoers is people just want to know that there’s blood, there’s a confrontation, there’s excitement.

Well, there is blood. There is blood.

There are deaths and surprises.

We tried to do that. We wanted to deliver that stuff. The fall from the tower, the lunar-rover sequence, the [mayday] thing, the underground lake, certainly; he climbs up a rocket, he has a zero G fight, he flies through the rings of a planet. I mean, we wanted to deliver some red meat. We absolutely did. By the way, there is no shame in that. Shakespeare was broad and subtle; that’s good stuff. So, we tried, and we tried to do it in our own way, of course, make it weird, unique, strange; in the lunar rover you can only hear what’s inside his helmet. It’s very weird for a chase sequence.

Yeah, you have meat and potatoes, but you also have some asparagus.

Exactly. That’s what we’re trying to do.

Ad Astra is in theaters September 20.

Thumbnail image: (c) Warner Bros.