The Boondock Saints Is Bad, but the Scathing Documentary About Its Toxic Director Is Mesmerizing

Nathan Rabin looks back at a fascinating portrayal of the power of delusion and the dangers of instant fame.

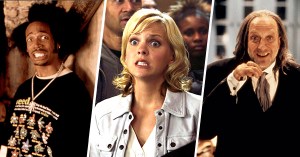

(Photo by ThinkFilm)

A couple months ago, it was announced that, after a blissful decade away from movies, The Boondock Saints writer/director Troy Duffy was returning to film with his third motion picture, The Blood Spoon Council, a gloomy new thriller that looks an awful lot like The Boondock Saints. On one level, the news isn’t terribly surprising. Despite bombing in theaters and with critics, The Boondock Saints has gone on to attract a huge and alarming cult enamored by its toxic brand of hyper-masculinity and “Tarantino For Dummies” macho posturing, and it was successful enough to inspire a tardy 2009 sequel in The Boondocks Saints: All Saints Day.

But Duffy is just as well-known — if not better known — as the subject, star, hero, anti-hero, and villain of Overnight, a movie so utterly damning in its depiction of Duffy as a boozy, obnoxious monster of id and ego that it’s surprising it didn’t kill his film career in its infancy.

The success of Pulp Fiction and the cult of Quentin Tarantino very briefly made auteurs the rock stars of the 1990s in the same way the comedy boom made stand-ups the rock stars of the 1980s. Duffy, however, didn’t just think of himself as a rock star of independent film, he thought of himself as a rock star, period. Not only did his script for The Boondock Saints briefly make him one of the hottest properties in Hollywood, but he was also part of a band called The Brood that was the subject of intense interest from labels like Madonna’s Maverick Records.

Around the same time, Duffy was making headlines for a deal in which Miramax head Harvey Weinstein, the all-powerful mogul who helped make Tarantino and Kevin Smith happen, bought the script for The Boondocks Saints for hundreds of thousands of dollars and additionally agreed to purchase the bar where Duffy worked (and where he wrote The Boondock Saints) so they could run it together.

Overnight is not the story of a good man corrupted by money, power, and success. Oh God, no. It’s pretty clear that Duffy was always a narcissistic dictator in the making. The money, power, and instant fame merely empowered Duffy further to be as horrible and destructive a human being as he could possibly be.

Overnight is not the story of a good man corrupted by money, power, and success. |

Duffy’s situation in the beginning of Overnight is genuinely unprecedented, ridiculous, and extreme. He briefly seems poised to rise from roughneck bouncer with a drinking problem to hotshot auteur with a major label recording contract and a documentary about his incredible ascent. If all that weren’t exciting and dramatic enough, he and one of the most powerful men in entertainment were about to become co-owners of the dive bar where he worked.

If Duffy ever experienced a moment of gratitude for being plucked from obscurity and elevated to great heights, he never expresses it here. The would-be auteur behaves as if the movie and music industries should be grateful he has chosen to favor them with his singular genius, and if the mindless peons he’s forced to interact with on his way up are appropriately deferential, then maybe he’ll show them mercy after he’s attained the Spielbergian power and influence he is absolutely guaranteed to achieve.

Duffy is so arrogant and naive that when he’s dealing with Harvey Weinstein, one of the most feared and intimidating men in the history of film, he behaves as if he’s negotiating with an equal, or even someone beneath him. Usually it’s depressing to see Weinstein crush the dreams and egos of young, ambitious filmmakers, but when the filmmaker in question is as unbearable (and seemingly anti-Semitic) as Duffy is, it’s hard not to take a certain evil delight in Weinstein’s Machiavellian power plays. Weinstein and Duffy are both bullying, arrogant monsters, so their battle is a little like Godzilla versus King Kong, only if Godzilla were actually Godzilla and King Kong were a child in costume. Needless to say, Duffy is the kid in the monkey suit.

When Weinstein fails to take concrete action to get The Boondock Saints made on a meaty $15 million budget (ostensibly enough to attract stars like a pre-Boogie Nights Mark Wahlberg), Duffy makes one of a series of astonishingly tone-deaf professional decisions and begins bad-mouthing him all around town.

If you were to make a list of people you would never want to antagonize as an aspiring filmmaker, Harvey Weinstein would be number one for decades. Yet Duffy seems convinced that his script is perfect, a guaranteed moneymaker, and that executives would happily knife each other for the right to bring his masterpiece to the big screen.

Not amused or impressed by his antics, Weinstein drops Duffy, who subsequently goes from red-hot to ice-cold. No matter how arrogant they are, a lot of filmmakers would learn from such an intense, traumatic experience. It would engender some sense of perspective, or gratitude, or an attitude adjustment. Not so, with Duffy.

There’s something inherently fascinating about oblivious narcissists. |

After Weinstein exits the picture, both literally and figuratively, Duffy somehow still manages to get the movie made, albeit with less than half the budget and no guaranteed distribution. It’s nevertheless enough to muster a relatively slick production with recognizable stars like Willem Dafoe. But instead of being humbled by his earlier experiences with Miramax and Harvey Weinstein, Duffy doubles down on his conviction. There’s no way his movie — and debut rock album — could ever be anything other than a success on par with Pulp Fiction, or Thriller.

There’s something inherently fascinating about oblivious narcissists. Duffy has no idea how the world sees him. He seems to think the documentary chronicling the making of his debut film will portray him like Francis Ford Coppola in Hearts of Darkness, the essential behind-the-scenes documentary on the making of Apocalypse Now, or Werner Herzog in the equally essential The Burden of Dreams. He labors under the delusion that he will come across as a fiery and passionate anti-hero, a larger-than-life genius willing to go through hell — and to subject others to torment — to realize his uncompromising vision. If the egos of lesser creatures have to be destroyed for this to happen, then that’s a sacrifice he’s happy to make.

Duffy bullies, taunts, and insults a whole lot of people over the course of Overnight, including the co-managers of his band, both of whom he financially screws over once his band finally lands a recording contract. In another example of Duffy’s poor judgment, the fired co-managers also happen to be the directors he hired to chronicle the making of The Boondock Saints — and that film eventually became Overnight. What Duffy clearly thought would be a celebratory demonstration of his genius instead became a delicious form of revenge exacted by two dudes who had even more reason to hate Duffy than most. Overnight is a fitting title, but Schadenfreude: The Movie or Screw Troy Duffy! would have been equally perfect.

Overnight goes further to recount the rise and fall of The Boondock Saints after it’s barely released and more or less goes direct to video, as well as the trajectory of Duffy and his band’s major label debut, which sells an impressively pathetic grand total of 690 copies. The film ends on an intensely satisfying note, though the poor members of Duffy’s former band are reduced to working day jobs, as Duffy is unable to secure work as a writer or director in the six years following The Boondock Saints.

Duffy’s downfall is an archetypal journey fueled by ego and booze and self-delusion. |

Overnight luxuriates in the downfall of a man who thought the world owed him everything (and better not be slow in delivering) crushed by the realities of the entertainment business and his own ego. It’s the story of a man convinced he would become the world’s greatest success and failed despite all of the hype of his Horatio Alger story-turned-harrowing cautionary tale.

Yet, in a way, Duffy hasn’t really failed at all, and that might actually be the most depressing aspect of his story. He was certain The Boondock Saints deserved an audience and would find one. He clearly saw it attracting a Pulp Fiction-sized blockbuster following, but instead it inspired a much smaller, much less discriminating cult of fans.

The self-mythologizing scumbag bouncer from Boston got to make his movie with stars like Willem Dafoe and Billy Connolly, and then he got to make a sequel. Now Variety has announced he’s got another film in the chamber, in addition to something called Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em and a comedy project called Black Ghost he co-wrote with Cedric the Entertainer. Oh, and in case you’re worried that Duffy is abandoning his beloved Boondock Saints franchise, don’t be: a TV spin-off series is on the way as well.

Duffy’s downfall, as documented in Overnight, is pure show-biz, an archetypal journey fueled by ego and booze and self-delusion. The entertainment industry’s apparent willingness to welcome Duffy back despite his horrific and very public failings as an artist and human being in hopes of cashing in on more Boondock Saints-style cult success is equally show-biz. There is no crime, moral or otherwise, that Hollywood can’t forgive if they think there’s a big payday in it for them.

Though Duffy has a pretty full slate ahead of him, I suspect that the only way he could ever make a good movie again would be if he signed on to star in a sequel to Overnight, but even a man as arrogant and deluded and in love with himself as Duffy clearly seems to be must know that that would be a terrible idea.

Original Certification: Fresh

Tomatometer: 78 percent

Re-Certification: Fresh

Nathan Rabin is a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin