The Works of Director Martin Scorsese

Is Martin Scorsese America’s greatest living director?

Is Martin Scorsese America’s greatest living director? It’s open to debate, but most movie buffs would agree that he’s created a body of work that is astonishing in its consistency and depth. Scorsese’s films contain many grand themes – organized crime, male insecurity, spiritual and moral uncertainty – and they’re executed with a level of artistic panache and intimate detail that few can match. Scorsese has exerted a profound influence on many important directors, including Quentin Tarantino, Spike Lee, and John Woo. And with apologies to Lee and Woody Allen, Scorsese is perhaps the greatest cinematic chronicler of New York’s distinctive social landscape.

While he’s considered one of the most important filmmakers to emerge in the 1970s, the 2000s have found Scorsese enjoying yet another fertile period, one that culminated with The Departed, for which he was granted his first Best Director Oscar. With his latest, Shutter Island, hitting theaters Feb. 19, we’ve decided to take a closer look at some of Scorsese’s most important films. However, rather than rank them by Tomatometer, we chose the movies that we feel best define the man’s art and stylistic breadth.

So join us for a tour of Scorsese’s career — a journey that will take us from the Bronx to Vegas, from Tibet to Boston, with plenty of interesting scenery along the way.

|

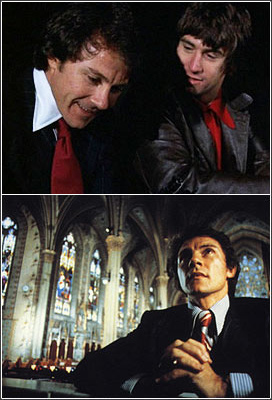

Release Date: October 14, 1973 – Scorsese initially considered entering the priesthood, but ultimately decided to enroll in New York University’s film school, where he directed a number of shorts before graduating in 1969. It was here that he met two of his most important collaborators: a young actor named Harvey Keitel, and Thelma Schoonmaker, who would become his longtime editor.

In 1967, Scorsese directed his first feature, Who’s That Knocking at My Door?, starring Keitel as a young Italian American wracked by Catholic guilt. The film had a palpable sense of place and a soundtrack heavy with contemporary rock, but was occasionally sidetracked by excessively arty touches. Scorsese’s second feature, the solid-if-unspectacular Bonnie and Clyde-aping Boxcar Bertha, was made under the tutelage of exploitation maestro Roger Corman. Fellow director John Cassavetes told Scorsese his next film should be more personal, and the result was Mean Streets, a powerful tale of urban sin and guilt that marked Scorsese’s arrival as an important cinematic voice.

Keitel stars as Charlie, a low-level Mafioso whose devout Catholicism and loyalty to an old friend, the violent and impulsive Johnny Boy (Robert DeNiro, in the first of his many great performances for Scorsese) fill him with conflict. His love life is no easier: he’s torn between Diane (Jeannie Bell), a stripper, and Johnny Boy’s epileptic sister Teresa (Amy Robinson), and his lustful feelings consume him with self-loathing. From Mean Streets‘ electrifying title sequence (featuring grainy super-8 home movies of the characters over Ronettes’ bittersweet plea “Be My Baby”) to its inevitably grim conclusion, the film provides a far darker, less glamorous tour of the gangster life than The Godfather — one filled with uneasy alliances, sudden, clumsy violence, and moral dread.

|

Release Date: May 30, 1975 – Before Mean Streets‘ release, Scorsese was hired to direct Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, a vehicle for actress Ellen Burstyn. It was his first Hollywood production, and though it’s atypical of the kind of movie Scorsese would become known for, Alice showcases the director’s skill for capturing the small details in the lives of people facing adversity. Alternating between fantasy and everyday life, this intelligent dramedy found Scorsese making the most overtly feminist film of his career.

Burstyn plays Alice Hyatt, a New Mexico housewife reeling from the death of her husband. She decides to sell her possessions and hit the road, with her young son in tow, to live out her dream of becoming a professional singer. She gets a job at a seedy lounge and finds a boyfriend in Ben (Harvey Keitel), but their relationship shatters when Ben’s violent temper emerges. She skips town again, taking a job as a waitress in Phoenix, where she bonds with her coworkers and begins an uncertain but strong romance with a lonely rancher named David (Kris Kristofferson). Burstyn’s powerful, risk-taking performance won her an Oscar for Best Actress, and the movie was adapted into a long-running sitcom, but Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore also proved that Scorsese was no one-trick pony; he could put his stamp on more conventional material.

|

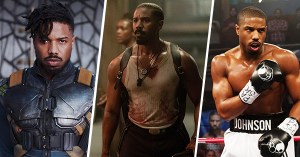

Release Date: February 8, 1976 – The nightmarish, endlessly compelling Taxi Driver confirmed Scorsese’s reputation as one of the foremost figures of the “Movie Brat” generation and provided Robert DeNiro with perhaps his most iconic movie role: Travis Bickle, a lonely, socially awkward, and dangerously volatile Vietnam vet turned late-night cabbie. DeNiro ad-libbed the movie’s most famous line (“You talkin’ to me?”), and Paul Schrader wrote the script (ominously, the Bickle character was partially based upon himself), but Scorsese pulled it all together, and the result is a haunted, unforgettable portrait of troubled masculinity and, by proxy, the urban malaise that plagued New York in the mid-1970s.

Bickle is an insomniac, and takes the graveyard shift driving a taxi around the city, frequently returning to Times Square. However, the more he sees during his nocturnal excursions, the more he seethes: he’s disgusted by the pimps, prostitutes, and junkies that regularly line the sidewalks of his route. One ray of light comes in the form of Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), a presidential campaign worker who’s intrigued by Travis. But after an ill-fated date to a porno flick, Travis begins to stalk Betsy — and the candidate as well. He also takes it upon himself to save Iris (Jodie Foster), a teenage prostitute, from her life on the streets — a life she seems unwilling to abandon. The movie builds to a feverish, brutal climax that finds Travis exploding with the violent rage that’s been simmering throughout the film, before ending with an oddly elliptical, dreamlike coda.

Taxi Driver won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar; it also inspired John Hinckley, Jr. to attempt to assassinate President Reagan. In other words, it’s cinema at its most primal and provocative, a masterwork that continues to leave audiences both profoundly moved and deeply unsettled.

|

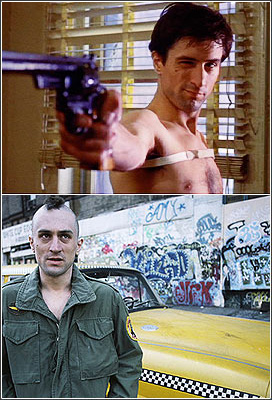

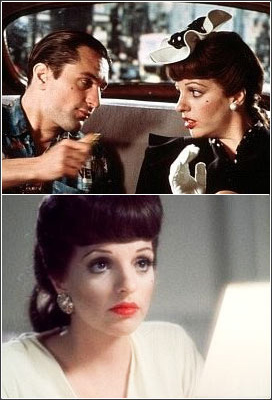

Release Date: June 21, 1977 – Today, New York, New York is probably best remembered for Frank Sinatra’s unparalleled rendition of its title tune, but it stands as a monument to the kind of epic, ambitious, auteur filmmaking that became virtually extinct by the end of the 1970s. Following the success of Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, Scorsese grafted his gritty realism onto the glitzy superficiality of the classic MGM musicals that he loved. The result is uneven, but while it bombed at the box office and remains one of Scorsese’s least-loved works, New York, New York features several show-stopping numbers and a distinctive style that’s all its own.

Robert DeNiro stars as Jimmy Doyle, a roguish jazz saxophonist who develops an on-and-off relationship with an up-and-coming singer named Francine Evans (Liza Minnelli). Their relationship is troubled from the beginning — Jimmy is a difficult customer, too temperamental for the responsibilities of love or his career. After a long split, the two find each other again, and this time, they’re at the top of their respective games — Francine’s topping the charts, and Jimmy has become a respected musician and club owner. In attempting an old-school rags-to-riches tale against a glittery backdrop, Scorsese can’t help but flesh out his characters’ painful insecurities, all of which makes for a stylistically jagged but often fascinating picture.

|

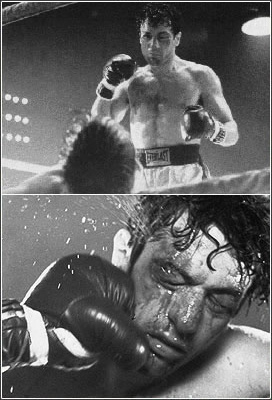

Release Date: December 19, 1980 – By the end of the 1970s, Scorsese’s career faced uncertain times. He directed the all-star rockumentary “The Last Waltz,” which chronicled the Band’s final gig, and the little-seen but queasily fascinating “American Boy,” a doc about Neil Diamond roadie and all-around sketchy character Steven Prince. But he had a bad drug habit, and Robert DeNiro, obsessed with bringing former middleweight champ Jake LaMotta’s autobiography to the screen, worked overtime to coax the director back into action. The result, Raging Bull, is considered by many to be Scorsese’s greatest achievement, a kinetic, on-edge portrait of a brutal, flawed man that never loses sight of its protagonist’s humanity.

The film charts the rise of LaMotta (DeNiro) through the middleweight ranks, aided and abetted by his brother Joey (Joe Pesci), who acts as his matchmaker and sparring partner. After throwing a fixed fight, LaMotta is granted a title shot by underworld fixers in the fight game, and also begins to court the teenaged Vicky (Cathy Moriarty), who he meets at a Bronx swimming pool. LaMotta is most expressive in the ring, delivering flurries of punches to his opponents; on the outside, though, LaMotta is fiercely possessive of Vicky, and his inability to control his emotions leads to a long, sad decline.

Filmed in tactile black-and-white, the movie is perhaps Scorsese’s most articulate meditation on male inadequacy, and its fight scenes are vivid and electric. Raging Bull was nominated for eight Oscars, and while winning two — Best Actor for DeNiro, and Thelma Schoonmaker for Best Editing — it failed to take home the Best Picture or Best Director awards, two honors that would elude Scorsese for years to come. Still, the director can take comfort in the film’s critical appraisal — the prestigious British magazine Sight and Sound called Raging Bull the best movie of the 1980s.

|

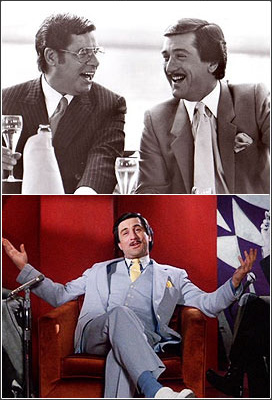

Release Date: February 18, 1983 – Simon Cowell should be thankful that the average deluded American Idol also-ran isn’t Rupert Pupkin. The single-minded fameball at the center of Scorsese’s pitch-black The King of Comedy is a type with whom we’ve become increasingly familiar in our tabloid-saturated times: Pupkin is needy, desperate, and willing to do anything to become famous. However, as played by Robert DeNiro, he’s a strangely sympathetic psychopath — and not an untalented one at that. Largely ignored and misunderstood upon its release, The King of Comedy today looks eerily prescient, and finds Scorsese dissecting our showbiz-fixated culture through the lens of the troubled loners that populated his previous films.

The lonely Pupkin amuses himself by seeking autographs and play-acting a late night talk show (he has a full set in his apartment, and banters with cardboard cutouts of the stars). One night, he has a chance meeting with one of his idols, chat host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis), who non-committally promises to check out Pupkin’s comedy act. Convinced he has his foot in the door, Pupkin shows up daily at Langford’s office until eventually he’s forcefully ejected. He then hatches a plot to kidnap Langford in a last-ditch effort to realize his dreams. With terrific performances from DeNiro, Lewis, and a borderline possessed Sandra Bernhard (who plays Pupkin’s accomplice), The King of Comedy is about as black as black comedies come, but it makes for riveting, prophetic entertainment. Most ironic line of dialogue, courtesy of Langford: “You don’t just walk onto a network show without experience.” Just you wait, buddy.

|

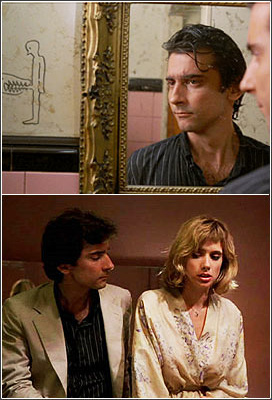

Release Date: September 13, 1985 – Like Taxi Driver, After Hours chronicles one man’s nightmarish, paranoid nocturnal journey throughout New York City. Unlike Taxi Driver, After Hours is a comedy — albeit an absurdist, Kafka-esque one. Scorsese had difficulty securing funding for some of his dream projects, so he decided to scale down for After Hours, adopting an underground, almost punk-rock aesthetic. The result was a different kind of Scorsese picture, an oddball movie that maintained the themes of his previous work while adjusting to the changing times.

Griffin Dunne stars as Paul, a corporate drone who meets an intriguing woman named Marcy (Rosanna Arquette) in a diner. He gets her number, and shortly thereafter she invites him to the apartment where she’s staying. But when Paul clumsily loses his money — and finds out that Marcy is more than he bargained for — he decides to head home. Subsequently, Paul is confronted with a bizarre series of circumstances — including subway fare increases, a bondage session, the loss of his keys, a suicide, Cheech and Chong, and a marauding mob that wrongly believes he’s a cat burglar — that prevent him from leaving Soho. Loaded with tension and wacky characters, this cult favorite found Scorsese making common cause with the burgeoning 1980s indie movement.

|

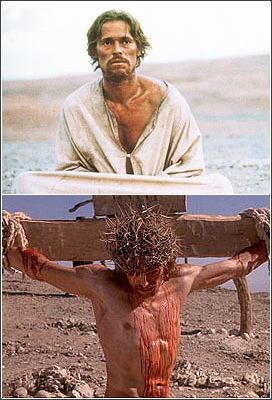

Release Date: August 12, 1988 – In the mid-1980s, Scorsese directed a pair of films that got him back in the mainstream’s good graces (The Color of Money, a sequel to The Hustler starring Tom Cruise and Paul Newman who won a Best Actor Oscar; and the long-form music video for Michael Jackson’s “Bad”). Next, he turned to a project of intense personal significance: an adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel The Last Temptation of Christ.

It was Scorsese’s most controversial film to date; a scene in which Jesus (Willem Defoe), in a dream, forsakes the cross to marry Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey) drew thunderous protests from religious groups (unfortunately for Scorsese, the brouhaha did little for the film’s commercial prospects, as it bombed at the box office). However, The Last Temptation of Christ was hardly an empty provocation; while the film deviates from Scripture, it’s a sincere, deeply-felt attempt by Scorsese, a dedicated Catholic, to explore the mysteries inherent in Jesus’ tale – most notably, the grey area between his divinity and his humanity.

The Last Temptation of Christ touches on many of the greatest hits from the Gospels, from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount to his Crucifixion. However, in drawing from the novel, Scorsese depicts Christ’s complex relationship with Judas (Harvey Keitel) and provides him with an inner monologue laced with uncertainty and distress over his supernatural visions. Each of the actors speak in their own accents, which lends an immediacy to the proceedings, and the on-location shoot in Morocco makes for a vibrant, mysterious stand-in for ancient Israel. The Last Temptation of Christ is austere, serious moviemaking, and though it isn’t always easy to watch, it’s a brilliant example of Scorsese’s ability make transcendent cinema out of inner tumult.

|

Release Date: September 19, 1990 – Raging Bull may be Scorsese’s most critically revered film, and The Departed was his biggest commercial success, but Goodfellas is probably his most cultishly adored picture. The tale of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), an Irish-Italian mobster-turned snitch contains one of the most oft-quoted lines of dialogue in any Scorsese film, courtesy of Joe Pesci as the psychopathic Tommy DeVito: “I’m funny how? I mean, funny like I’m a clown? I amuse you?”

It’s easy to see why Goodfellas continues to resonate: It’s brilliantly acted, shockingly violent, unnervingly tense, and wickedly funny. It also contains one of Scorsese’s best soundtracks, utilizing the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” and Derek and the Dominoes’ “Layla” to evocative effect. And once again, Scorsese is brilliant at capturing the distinctive milieus and daily rhythms of the underworld and bonds that form between those who live outside the law.

Hill is a Brooklyn kid who’s always dreamed of being a part of the Mafia. His wish comes true when he teams up with such local toughs as DeVito and Jimmy “The Gent” Conway (DeNiro) for a series of burglaries and hijackings. After attempting to recover money from an indebted gambler, many of the wiseguys are sent to prison, where Hill starts dealing drugs to support his family. Upon their release, the gang executes a spectacular heist of money and jewelry from JFK Airport, a crime that breaks the tight bonds of the gang. Hill convinces Conway and DeVito to join him in the drug trade, but soon, the wiseguys’ trust in one another has completely eroded. Based upon true events, Goodfellas feels absolutely authentic, not least because Scorsese is brilliant in depicting the inherent appeal of the gangster life — and its dark consequences.

|

Release Date: October 1, 1993 – After a tense, assured remake of Cape Fear in 1991, Scosese did another U-turn. When it was released in 1993, The Age of Innocence seemed like a radical departure for the director; he took time out from chronicling New York’s gangsters and loners to craft a lush period piece about the city’s society life of the 1870s. However, like many of Scorsese’s other films, The Age of Innocence, based upon Edith Wharton’s novel, explores the social codes of a time and place that govern – and restrict – people’s behavior; Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Countess Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer) are as bound by the conventions of their environs as Charlie and Johnny Boy were in Mean Streets. They may not have the outlets for emotional release afforded Scorsese’s other protagonists, but their passions run just as deep. The result is the director’s prettiest film, and a deeply poignant one.

Archer is an upstanding (but questioning) member of New York’s upper crust at a happy point in his life – he’s engaged to beautiful socialite May Welland (Winona Ryder). However, May’s cousin Ellen has just arrived in town, causing a scandal — she was unhappily married in Europe, and rumor has it she had an affair with a commoner. Seeking a divorce from her husband, she consults Archer, an attorney, for advice. Though he’s sympathetic to Ellen and feels she shouldn’t be shunned because of her marital status, Archer asks her to consider the social ramifications of her decision. What follows is a delicate dance between Archer and Ellen, who are powerfully attracted to one another; Archer sees possibilities for happiness with this new woman beyond his humdrum marriage.

Scorsese’s pacing is stately, but The Age of Innocence succeeds where many period-pieces fail, showing impeccable period décor as well as passion and, ultimately, bittersweet longing.

|

Release Date: November 22, 1995 – Upon its release in 1995, critics were somewhat disappointed by Casino. With the focused brilliance of GoodFellas fresh in their minds, many felt Casino was simply a well-crafted yarn that lacked the narrative focus to achieve its ambitious aims. However, seen 15 years later (and endless replays on cable), Casino has aged remarkably well; its telling of Vegas’ Genesis story is complicated, to be sure, but Scorsese deftly balances the historical details with the human drama, and he’s helped immeasurably by excellent performances from Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and Sharon Stone (in arguably her greatest performance).

Casino is the story of how Las Vegas went from a sleepy desert outpost to a major tourist destination, told primarily through the eyes of Sam “Ace” Rothstein (DeNiro), a master sports handicapper recruited by the mob to manage the Tangiers Casino – and skim as much money as possible. Rothstein is a great success at generating illicit revenue, but his personal life takes a perilous turn when he marries former prostitute Ginger McKenna (Stone) and his old buddy, the violent, impulsive Nicky Santoro (Pesci) is brought in to provide muscle. Soon, Ace is besieged by the FBI, his closest associates, and, eventually, the mob itself.

Casino is filled with fly-on-the-wall details about how criminal organizations function – it’s a secret history of one of America’s most iconic cities, and a reminder of the criminality that helped build it. But it’s also a story about how human failings can derail even the most seemingly foolproof of plans.

|

Release Date: December 25, 1997 – In The Sopranos, there’s a scene in which a young Mafioso sees Scorsese (played by Anthony Caso) entering a nightclub and shouts, “Marty! Kundun — I liked it!” Coming on the heels of the gangster epic Casino, Kundun took some by surprise, but this biography of the 14th Dalai Lama can be seen as a companion piece with The Last Temptation of Christ. Made in Morocco with a cast of non-professional actors, it’s a devout, patient, gorgeously-shot work — and if it doesn’t delve deeply enough into the inner workings of His Holiness, Kundun provides both a dramatic recreation of the conflict between Tibet and China, as well as a crash course in Buddhist principles and rituals.

Kundun begins in 1937, with a group of lamas searching for the latest incarnation of the Dalai Lama. They discover a two-year-old in a farming village near the Chinese border, and the boy is deemed a worthy successor after successfully selecting which items randomly laid on a table belonged to the previous Dalai Lama. The boy grows into his role, with intensive study of Buddhism and a preternatural grasp of political affairs. However, he’s tested when China annexes Tibet; after a few promising meetings with Mao Zedong, the Dalai Lama (played as an adult by Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong) realizes that Tibet’s way of life is under attack.

Featuring a moody, evocative score by Philip Glass, Kundun is one of Scorsese’s most visually ravishing pictures, and while it occasionally veers into standard biopic tropes, it’s a reverent, impassioned work. Kundun‘s sympathetic treatment of Tibet irked Chinese authorities, who permanently banned Scorsese and screenwriter Melissa Mathison from entering the country.

|

Release Date: December 20, 2002 – After the underrated Paul Schrader collaboration Bringing Out the Dead, Scorsese tackled a long-gestating dream project: Gangs of New York. Loosely based upon Herbert Asbury’s 1928 true crime book of the same name, Gangs was an attempt by one of cinema’s poets of organized crime to explore the roots of American gangsterism — and its inextricable ties with society and government. Set in Civil War-era Manhattan, the movie depicts a city teeming with hatred and violence — Gangs‘ Five Points setting is worlds away from the genteel folks living across town in The Age of Innocence. Costing more than $100 million and clocking in at nearly three hours, Gangs of New York can feel overstuffed, and it sometimes lacks historical context, but it’s always watchable, thanks to the impeccable production design and a gonzo performance from Daniel Day Lewis.

Leonardo DiCaprio (in his first performance for Scorsese) stars as Amsterdam, the son of Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson), an Irish immigrant gang leader. Vallon is killed in a gang war by Bill “The Butcher” Cutting (Lewis), who leads the virulently anti-immigrant Natives gang. Amsterdam is raised in a home for orphans, but upon his release as a young man, he returns to the Five Points section of New York, where Cutting rules with an iron fist. Amsterdam becomes Cutting’s right-hand man, while secretly planning to kill him. Meanwhile in the mayor’s office, Boss Tweed schemes to employ the gangs’ mutual antipathy to his political advantage. However, forced conscription of Irish immigrants into the Union army threatens to bring New York to a boil. Given that Scorsese had wanted to make this film for decades, his insistence on packing in as many events as possible is understandable, but it can make for a grueling experience. Still, Lewis is mesmerizing to watch, and rarely has a period piece captured an era with such acute attention to detail.

Gangs won Scorsese his first Golden Globe for Best Director, but he couldn’t repeat at the Oscars, losing Best Director and Best Picture to The Pianist and Chicago, respectively.

|

Release Date: December 25, 2004 – As the old saying goes, if you’re poor, you’re crazy, but if you’re rich, you’re eccentric. Few lived this maxim quite like Howard Hughes, who was a business tycoon, film producer, aviation pioneer, and germophobic loon. Scorsese’s handsome, sprawling biopic brings Hughes – or at least the idea of the man – to modern audiences. As history, The Aviator is often dubious (and it downplays some of Hughes’ less amusing idiosyncrasies — his enthusiastic, lifelong racism, for instance). However, Like Casino, The Aviator charts a historic moment before American business became more corporatized – when go-for-broke dreamers could change the status quo.

Leonardo DiCaprio plays Hughes as a cocksure, free-spending optimist; when we first meet him, he’s ignoring all sensible budgetary concerns to make Hell’s Angels the most spectacular picture possible. He also has a passion for fast airplanes and beautiful women, heedlessly breaking speed records, spearheading grand designs for flying machines, and courting Hollywood stars like Katherine Hepburn (Cate Blanchett). And as the owner of TWA, he’s locked in battle with Juan Trippe (Alec Baldwin) and Pan-Am for control of the airline industry. However, Hughes’ paranoia and obsessive-compulsive behavior contribute to his eroding social stature – by the end of the film, he’s sequestered himself in his private movie theater, terrified of germs and antagonists. Scorsese captures the glamour and ambitious spirit of Hughes’ era, and DiCaprio is outstanding at projecting a boyish recklessness that hardens into madness.

If The Aviator whitewashes certain aspects of Hughes’ life, it’s never less than watchable and breezily compelling. And though it didn’t win Best Picture, The Aviator took home five awards on 11 nominations.

|

Release Date: October 6, 2006 – For years, Scorsese was to the Oscars what Susan Lucci was to the Daytime Emmys – a perennially deserving runner-up. When The Departed won both Best Picture and Best Director, some surmised that it was not simply because of the quality of the film – it was for the whole of Scorsese’s body of work. Still, if The Departed is a notch below GoodFellas or Raging Bull, it’s still a remarkable picture – an entertaining, complex cat-and-mouse tale that traded the mean streets of New York for South Boston without sacrificing Scorsese’s acute eye for regional detail.

A loose remake of the Hong Kong crime drama Infernal Affairs, The Departed is directed with matchless assurance from the man who wrote the rulebook on this kind of picture – and still finding new ways to expand the boundaries. (It should not pass without mention that Scorsese bookended The Departed with two fine rockumentaries: No Direction Home, a mammoth, insightful exploration of Bob Dylan’s early career that aired on PBS, and Shine a Light, an exhilarating live document of the still-spry Rolling Stones).

Irish Mafia head Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson) has a plan to stay one step ahead of the Boston authorities: utilizing Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon), who has just graduated from the Massachusetts State Police Academy, as his personal spy. However, the cops have a mole of their own: Billy Costigan (Leonardo DiCaprio), who quickly earns Costello’s trust. Before too long, it becomes apparent that both sides have people on the inside; as a result, Sullivan and Costigan work frantically to root out their counterpart. The Departed is filled with fine performances – Nicholson is at his grouchy, angry best here, and features juicy supporting roles for Mark Wahlberg, Martin Sheen, Vera Farmiga, and Alec Baldwin, to name just a few. But ultimately, The Departed is Scorsese’s triumph – a film with the grit and emotional weight that compares favorably to this cinematic master’s finest work.