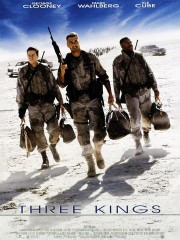

5 Reasons Why Three Kings Is the Best War Satire of the Last 20 Years

On its 20th anniversary, we look back at David O. Russell's eerily prescient heist movie, whose astute observations and moral complexity are just as relevant now as they were then.

(Photo by Warner Bros. courtesy Everett Collection)

There were a handful of forgettable war-related films released in 1999: The General’s Daughter, All The King’s Men, the Robin Williams-starrer Jakob The Liar. And then there was Three Kings (Certified Fresh at 94%), part action comedy, part heist movie, and 20 years later, still holding up as one of the best — and most subversive — war films ever made.

Directed with adrenalized panache by David O. Russell (Silver Linings Playbook, American Hustle), Three Kings followed on the heels of Steven Spielberg’s heroic 1998 WWII epic Saving Private Ryan, which canonized the sacrifices made by the Greatest Generation. But Russell had no such patriotic flag to wave. Like Catch-22, Three Kings satirically probes the insanities of war; like Apocalypse Now, it revels in surreal set pieces and sharp visual juxtapositions; like M*A*S*H, it mixes black humor with moral complexity.

Its heroes are reluctant ones, soldiers who start out consumed by their own self-interest until forced by untenable circumstances to take a moral stand.

IT HAS A KILLER VISUAL LOOK

Inspired by color photos of the war that appeared in newspapers at the time, Russell and his cinematographer, Newton Thomas Siegel, devised a saturated, blown-out look for the Iraqi desert (actually Arizona) in the film. They increased the contrast and graininess and bypassed the bleaching stage of the film process, giving the desert landscape a foreboding, surreal look, which set the visual template for other films about contemporary wars that followed. The Iraqi village was designed by production designer Catherine Hardwicke, who served the same role on films like Tombstone and Tank Girl and would go on to direct the first Twilight and Lords Of Dogtown.

IT MAKES ASTUTE POLITICAL POINTS WITHOUT BEING PREACHY

(Photo by Warner Bros. courtesy Everett Collection)

Russell exposes the hypocrisy of American foreign policy in the Middle East and indicts the Bush Administration for its abandonment of anti-Saddam insurgents – whom the U.S. had encouraged to rise up against the Iraqi dictator – all without pedantic speeches or heavy-handed scenes. The soldiers who steal back the Kuwaiti gold from Saddam – George Clooney, Ice Cube, Mark Wahlberg, and Being John Malkovich director Spike Jonze – spend the latter part of the film, at great risk to themselves, helping a group of insurgents reach the Iranian border, foreshadowing the refugee crisis of future wars to come.

IT HAS THE MOTHER OF ALL INTERROGATION SCENES

What’s a good war movie without at least one hard-to-watch interrogation scene? Most of these scenes tend to follow a simple formula: someone, usually a soldier, is captured behind enemy lines and tortured for information. But the scene between Moroccan actor Saïd Taghmaoui as an Iraqi army officer and Mark Wahlberg as the captured American soldier gets up close and personal in a way few of these scenes manage to.

While the Iraqi does torture Wahlberg’s character with electric shocks, he’s no faceless sadist; our sympathies are engaged when we learn he’s lost his young son and daughter to American bombing raids. But the capper comes when Taghmaoui forces oil down Wahlberg’s throat, a searing indictment on what many felt was the real point of America’s intervention in Kuwait: to protect its oil reserves in the Middle East.

IT’S THE FIRST WAR FILM TO SHOW GRAPHICALLY WHAT A BULLET CAN DO TO THE HUMAN BODY

Russell was concerned about viewers being anesthetized to gun violence; his answer was to give the audience the uniquely visceral experience of how a bullet traumatizes the human body. In the scene, Clooney lectures his men: “What makes any gunshot wound bad, provided you survive the bullet, is something called sepsis. Say a bullet tears into you right now. It creates a cavity of dead tissue, the cavity fills up with bile and bacteria, and you’re f—ed.” As the soldiers listen, the camera tracks a bullet as it smashes into the body, tearing through flesh and filling the organs with bile.

While doing press for the film, Russell grew so irritated with a reporter’s questions that he made up a story about how the bullet scene was done using a real corpse. Needless to say, the studio did not find it funny.

IT TRANSFORMED GEORGE CLOONEY’S CAREER

In 1999, Clooney was still playing a doctor on NBC’s hit TV show E.R. After the disappointment of 1997’s Batman & Robin (11% on the Tomatometer), he was desperate for meatier roles in prestige projects. In particular, he wanted the role of Three Kings’ disillusioned Special Forces Major Archie Gate (it didn’t hurt that Warner Bros., who produced Three Kings, also produced E.R.), but his relationship with Russell was volatile from the start. The weather on set in Arizona was hot, and the shoot proved to be chaotic. Clooney would often show up on set only to find that Russell had completely rewritten his scenes. As recounted on Slate.com, the two famously came to blows after Clooney objected to Russell physically manhandling an extra on the set.

Nevertheless, the film helped to cement Clooney as a leading man, as he jumped to starring roles in The Perfect Storm and O Brother, Where Art Thou? Late in Three Kings, after Jonze is killed and Wahlberg is wounded by a sniper, he even gets an E.R. moment, placing a flutter valve in Wahlberg’s chest to allow air to escape from a punctured lung.

Three Kings opened on October 1, 1999.