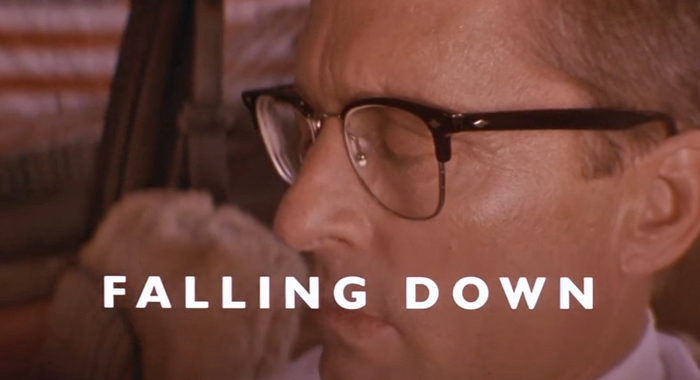

1993’s Falling Down is an Eerie Reflection of Modern America’s Persecution Complex

Joel Schumacher's controversial thriller starring Michael Douglas is as tone-deaf and histrionic now as it was at the time of its release.

Michael Douglas may be the most privileged man alive. His daddy Kirk was an incredibly rich, powerful, and famous movie star and producer, and he himself has graced the big screen in some of our biggest films for decades. Hell, even before Michael was a top box-office attraction, he won the Academy Award for producing One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, a property his old man bought and gave to him the same way mortals might give their child a beat-up old car of theirs as a graduation present.

Yet Douglas’ status as the cocky, smirking embodiment of white male privilege has somehow not kept him from repeatedly getting cast, or casting himself, as white men afflicted by the evils of non-white, non-men. In Fatal Attraction, his saintly, selfless adulterer is cruelly victimized by a mentally ill, sexually aggressive woman with some unfortunate ideas about rabbits. In Basic Instinct, meanwhile, his saintly, selfless horn dog is similarly terrorized by one of those insatiable wealthy bisexual serial killers who just won’t let straight men like him be.

Evil, inscrutable Japanese gangs joined the list of groups terrorizing one of Douglas’ rugged protagonists in Ridley Scott’s blindingly slick, morally empty Black Rain, while Disclosure, based on the odious best-seller from an increasingly unreadable Michael Crichton, found him very plausibly being sexually harassed by a hot-blooded sexpot played by an ascendant Demi Moore.

In that respect, Douglas’ unlikely role as the embodiment of impotent white rage in Joel Schumacher’s controversial 1993 drama Falling Down represents the simultaneous apex and nadir of the actor’s strange obsession with playing characters who feel hopelessly victimized despite belonging to a demographic that has historically wielded enormous, generally unchecked power.

I was tempted to re-visit Schumacher’s sweaty, failed attempt at relevance because the film foreshadows and anticipates the deep, frightening strain of unhinged white male rage powering Donald Trump’s political assent. Trump has played unashamedly to his white male Christian base’s feelings of victimhood, to the sense that they are now the real persecuted class and that only a man like Trump will be able to stand up to the forces of common decency — I mean, political correctness — and finally restore the poor, embattled white man to a place of respect and dignity in our society.

|

Seldom has the catalyst for a film protagonist’s rage felt so much like the kind of petty nonsense Andy Rooney devoted his entire useless career to dissecting. |

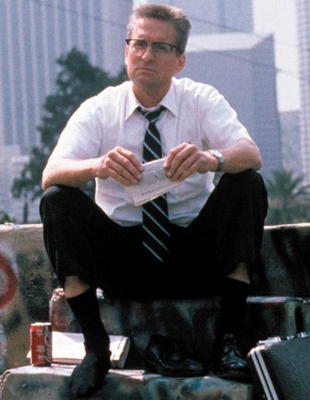

The film opens with Douglas’ laid-off former defense worker — who is never named, only referred to by his vanity license plate (“D-fens”) — marinating in a traffic jam Schumacher and cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak depict as the 10th circle of hell. Douglas’ alpha-male good looks are masked by his egregiously dorky attire: ugly, blocky glasses, a tight dress shirt, and a tie. His character begins the film on the verge of a nervous breakdown, and after an encounter with an Asian convenience store clerk goes awry, he decides to exact vengeance upon a world he is convinced hates him and everything that he stands for. D-Fens starts off wielding a baseball bat as his weapon of choice before picking up a proper arsenal from cartoonish toughs who, despite being decades younger than our star, are clearly no match for his rage-triggered super-strength. Our anti-hero then lashes out against everything from fast food restaurants that don’t serve breakfast past a certain time and con artists with unconvincing spiels to uppity construction workers and plastic surgeons who make too much money while men like the protagonist apparently make too little, or made too little before they became unemployable. Seldom has the catalyst for a film protagonist’s rage felt so much like the kind of petty nonsense Andy Rooney devoted his entire useless career to dissecting.

Falling Down wants to be a 1990s update of Joe, a zeitgeist-capturing 1970 character study about a demented, hippie-hunting reactionary lunatic at war with the forces of social progress, which made Peter Boyle (who played the title character) a star. But Falling Down never comes close to realizing its ambitions, pretensions, and aspirations. It’s dodgy, disingenuous, deeply confused schlock that thinks it’s art, a scummy, simplistic potboiler that all but nominates itself for a dozen Academy Awards.

The film was supposed to prove that, with the right script, star, and subject, Joel Schumacher, who more or less personified empty show-biz glitz even before he made Batman & Robin, could make a film that was uncharacteristically serious, smart, and even important. Schumacher and his collaborators set out to make the kind of message movie that ends up on the cover of Time for saying something profound about The World We Live In Today.

The performances here are so big and broad that they suggest that Schumacher’s primary direction to his actors was to gesticulate so wildly and yell so loudly that someone thousands of feet away would still know exactly what they were saying and doing. Douglas has a few nice moments when the deafening volume and comic book luridness of the film give way to something quieter and more reflective, but for the most part he’s embarrassingly hammy and over-the-top. With his nerdy glasses, sweat-soaked dress shirt, tie, and briefcase, he looks and acts less like an ordinary man driven to violent and insane extremes than a man wearing a “geek” Halloween costume.

|

He looks and acts less like an ordinary man driven to violent and insane extremes than a man wearing a “geek” Halloween costume. |

The angry nerd’s crime spree brings him to the attention of cop Martin Prendergast (Robert Duvall), whose final day as a police officer becomes a whole lot more dramatic thanks to our anti-hero’s rampage. Prendergast is himself a groaning, lazy stock character: a cop on the verge of retirement who is getting too old for this s—. He also has a dead child and a wife who is mentally ill, both of whom are referenced constantly, the latter often in a way that underlines how D-Fens and Prendergrast may be on opposite sides of the law but are ultimately mirror images of each other. The anti-hero and the man who must bring him down share a strong but unspoken bond as old-fashioned men lost in a newfangled world full of minorities and women and arbitrary rules.

Prendergast realizes that D-Fens is a precious and rare creature, a veritable unicorn: a white, middle-aged man in white, middle-aged man attire in the mean streets of Southern California, albeit one who looks like a Dilbert cosplayer lost in the wrong neighborhood. And because Falling Down is written by a white man, directed by a white man, and stars an icon of perpetually threatened whiteness, the only character we’re supposed to care about is the white dude scoring symbolic point after symbolic point over an endless series of broadly drawn straw men and women. Perhaps the most generous reading of the film is that it allows us to see life through D-Fens’ perspective, as an endless series of minor annoyances and inconveniences that collectively add up to an insult to his essential being.

Instead of dissecting and deconstructing racism and white privilege, Falling Down ends up reinforcing them at every turn. The film is filled with sweaty, boorish caricatures of Latino gang-bangers; heavily-accented Asian store-keepers who seemingly take malicious delight in verbally abusing their customers; scary, desperate homeless people; and various other folks at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder to whom the film nevertheless feels duty-bound to deliver a few swift kicks. The film tries to undercut the offensiveness of depicting its supporting characters in this way by adopting a cast of blandly multi-cultural cops to trade generic banter with Prendergast, as if doing so excuses the film’s extensive reliance on racist stereotypes.

We’re not necessarily asked to identify with D-Fens, or to root for him, yet the film keeps betraying its unearned respect for him. Throughout the film, cops interviewing witnesses of D-Fens’ rampage are repeatedly surprised and impressed by his ethics, by the way he would terrorize and threaten and point guns at innocent shopkeepers but not do anything unforgivable, like shoplifting. They are way too impressed to discover that their suspect is that most common of pop-culture archetypes, the vigilante with a strong moral code.

|

D-Fens wants to return to an idyllic time that probably never existed. |

Just as folks like David Duke have given Trump a chance to delineate between his more subtle form of racism and xenophobic hatred and Duke’s more overt, less artful variety, Falling Down further lets its protagonist off the hook. Frederic Forrest shows up as a military store proprietor who gushes about the wonders of the gas chambers and the awesomeness of the Holocaust, just so that D-Fens can take a bold moral stand and say that, yes, while he may be racist and angry and entitled and psychotic, at least he’s not a neo-Nazi aching for the return of concentration camps. Forrest’s twitchy, bug-eyed, hollering performance suggests Herman Hermann, the one-armed Simpsons conspiracy nut who similarly runs an Army-Navy surplus store in Springfield, only more cartoonish and less multi-dimensional. To really drive home the point, D-Fens ultimately kills the white nationalist lunatic, but only after he artfully establishes their similarities by repeating to him, “We’re the same,” and D-Fens replies with an equally artful “We’re not the same.”

At this point, the film stops being Nerdlinger’s Racist Revenge, as D-Fens swaps his geek costume for some vaguely paramilitary gear and his quest for vengeance enters a bleak endgame. The protagonist talks about going home; he means that he wants to get back to a place, emotionally and otherwise, where his ex-wife and daughter think of him as a loving husband, a good provider, and an involved father, not the violence-prone rage monster they have a restraining order against.

On a literal level, D-Fens wants to return to his ex-wife and daughter’s home so he can give his daughter her birthday present. On a more metaphorical level, D-Fens wants to return to an idyllic time that probably never existed, when a white man with a college degree was promised an attractive wife and lifelong marriage, two beautiful children, and a big house they could afford. Oh, and women and minorities knew their place, humbly accepted subordinate roles, and meekly, slowly worked towards social progress, albeit in ways designed not to make the white establishment feel threatened or uncomfortable. That’s the fantasy Trump is talking about when he vows to “make America great again,” and in both Trump’s case and the case of sad, pathetic D-Fens, they’re clearly only concerned with making America a more comfortable, endlessly affirming place for white men like themselves.

Watching Falling Down in 2016 is a curious experience in that it should speak powerfully and directly to a strange and intense cultural moment and a form of rage with the potential to change our country and world in terrifying ways. The film should comment incisively on our current political and social landscape. Instead, it feels just as wrong, over-the-top, and tone-deaf now as it did back when it was released. I re-watched the movie hoping that it might teach me something about the roots and nature of white anger. Instead, it only ended up feeling like a histrionic wish-fulfillment fantasy for Trump supporters.

Original Certification: Fresh

Tomatometer: 73 percent

Re-Certification: Rotten

Nathan Rabin is a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin