Robert Altman’s The Player is a Meta Exploration of Hollywood’s Twisted Self-Obsession

Nathan Rabin breaks down how this 1992 show-biz satire both critiqued the industry and restored Altman to the A-list.

Movies about movies generally don’t fare well at the box office, and they tend to get mixed-to-dire reviews. Yet Hollywood keeps making ostensibly scathing satires exposing the film industry as a snake pit of phonies, opportunists, sycophants, and worse. It seemingly can’t help itself.

The deluge of unwanted, unloved show business satires is partially attributable to the toxic self-absorption of Hollywood folk. People involved in the industry find nothing more fascinating than their own quirks, pretensions, and excesses. In that respect, they’re a product of deep-seated narcissism, even as they take gleeful satirical aim at the narcissism endemic in show business.

This might seem masochistic from the outside, but really it’s just another form of egomania. Even the most brutal, eviscerating takedown of Hollywood flatters show business by treating it as a subject worthy of being targeted.

So when Robert Altman finally got around to making a movie world satire with his 1992 comeback hit The Player, I suspect Hollywood was flattered rather than insulted that one of its prickliest geniuses considered their industry worthy of his mockery and scorn. The Player is entertaining but endlessly glib, a deeply superficial look at a deeply superficial industry. It’s minor Altman elevated to major status due to its commercial and critical success and the pivotal role it played in returning Altman to the ranks of A-list studio filmmakers.

The glibness begins with a long, uninterrupted eight-minute shot that, like all uninterrupted shots of that length, serves dual purposes. First and foremost, it draws us into the world of the film, a world of free-floating desperation and naked greed, where everyone, from executives to screenwriters to actors, speaks the mercenary, reductive language of “the pitch.” The Player is full of the kind of comically inane pitches ubiquitous in show business satires, particularly the ones that combine two wildly dissimilar but well-known titles, like “Ghost meets The Manchurian Candidate.”

|

People involved in the industry find nothing more fascinating than their own quirks, pretensions, and excesses. |

More importantly, an unedited shot of that length serves to call attention to itself and to the director. The more you know about Altman’s history, the more you get out of the film itself, in part because the film’s gallery of famous people includes much of Altman’s repertory company as well. This opening shot gives us an impish first impression of a broad cross-section of Hollywood phonies while at the same time establishing an achingly meta, self-referential tone that carries through to the final frame.

These players and would-be players are divided by class, by money, by success, but they are united in their desperation, in their feverish quest to get ahead — or at least not fall behind — in a business that is equal parts sadistic and insane. Nobody is exempt from this free-floating terror, not even legends like Buck Henry, who shows up in the opening shot to pitch a sequel to The Graduate featuring a stroke-afflicted Mrs. Robinson.

Altman can be an extraordinarily subtle filmmaker. He’s at his least subtle here, though, when he has Walter Stuckel (Fred Ward), who works in security at the studio, lament the kinetic, MTV-style editing that has replaced the kinds of long, uninterrupted takes you found at the beginning of Touch Of Evil. Of course, when Stuckel references the opening shot in Touch Of Evil, he is also implicitly acknowledging the shot he’s in, but it doesn’t stop there. The Player is a film of overkill (even the plot hinges on a man who kills one more person than is absolutely necessary) so Stuckel continues singling out similar shots in Absolute Beginners and The Sheltering Sky.

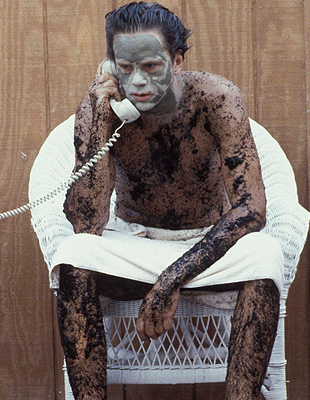

Tim Robbins plays studio executive Griffin Mill, who begins the film in a state of perpetual distraction. Robbins plays Griffin as a man whose attention is far too valuable to waste on insignificant screenwriters or underlings. If he believes in anything, which is doubtful, it’s in Hollywood formula. And if he gives 15 percent of his attention to any one person, it’s a mark of extravagant generosity; most of the peons in his life get far less.

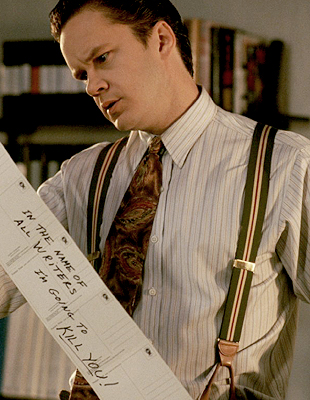

This includes David Kahane (Vincent D’ Onofrio), a pretentious, bespectacled, struggling screenwriter in the Clifford Odets/Barton Fink mold who sees Griffin not just as a powerful man who made, and makes, him feel powerless, but as something close to the embodiment of Hollywood evil. Griffin feels threatened by him, so in a bid to neutralize this potential threat to his life, he tracks down the scruffy scribe at a theater showing not just an arthouse movie but the arthouse movie: The Bicycle Thief.

At the theater, Griffin masquerades unconvincingly as a man who cares about art, and even less convincingly as a man interested in whatever is rattling around inside the failed screenwriter’s frazzled brain. For the briefest of moments, it appears these two wildly dissimilar men may not be perpetually at war, but when David starts antagonizing Griffin about the buzz that rival Larry Levy (Peter Gallagher) will usurp his place in the show-biz hierarchy, Griffin flies into a rage and accidentally kills the hapless writer.

|

Within the world of the film, screenwriters are disposable, while men with the power to green-light movies are worshipped like Gods. |

Griffin then goes about seducing David’s ice queen girlfriend June Gudmundsdottir (Greta Scaachi), who doesn’t seem particularly concerned about her partner’s disappearance. Griffin assumes that it was David who was sending the postcards, but they keep coming even after his death, and he seems far more concerned with staying in the game, professionally, than he is with staying out of jail.

He needn’t worry. In The Player, the life of an angry, struggling screenwriter in a town and industry full of angry, struggling screenwriters doesn’t amount to much, if it amounts to anything. That’s also true outside of the film’s world as well, but The Player is relatively unique in Altman’s filmography in that it seems to belong as much to its writer as it does to its director. Altman is famously cavalier about ignoring scripts, including the Oscar-winning ones for M*A*S*H and Brewster McCloud, the latter of which was one of the hottest screenplays in show-business before Altman scooped it up and made a movie that bore almost no resemblance to it. Yet in The Player, Altman treats Michael Tolkin’s adaptation with uncharacteristic reverence. Within the world of the film, however, screenwriters are disposable, while men with the power to green-light movies and realize dreams — men like Griffin — are worshipped like Gods.

The people in The Player see everything in terms of cinematic formula. They’re not human beings, they’re characters, and they similarly see their lives and careers in cinematic terms. There’s a great scene early on when Larry Levy uses random articles in the newspaper to illustrate that there’s no story too dry or depressing that it cannot be transformed into a crowd-pleasing Hollywood melodrama. All you need to do is add some laughs, some sex, some heart, and a happy ending, and suddenly you have a movie exactly like every other.

The characters in The Player seem wholly aware they’re in a movie. For them, life is movies, and Altman further blurs the line separating the (just barely) fictional world of his film from the real world of Hollywood by filling the film with dozens upon dozens of cameos from famous people playing themselves, from Burt Reynolds to Altman protege Alan Rudolph. This never-ending string of big name cameos functions as commentary on the movie world’s obsession with celebrity, but from a commercial standpoint, it never hurts to have as many big stars involved with a project as possible. This also helps explain why The Player feels more like a good-natured goof than a vicious takedown. Altman may despise the business, but he loves actors, and movies, and human behavior, and the cynicism at the core of the film is leavened by his palpable affection for his collaborators.

The Player ends on a distinctly self-satisfied and deeply meta note. A movie that was pitched by a pair of characteristically struggling screenwriters (played by Richard E. Grant and Dean Stockwell) as a raw, troubling slice of unvarnished reality with no big names to distract from its brutal truths is instead transformed into a gossamer ribbon of pure fantasy that’s zero reality and all star power.

|

The cynicism at the core of the film is leavened by Altman’s palpable affection for his collaborators. |

And because the “reel” world of The Player is a funhouse mirror reflection of its real world, our aloof, unsympathetic, murderer of an anti-hero gets a Hollywood-style happy ending of his own as well. Real life is not governed by the dour, moralistic dictates of the Hays Code, which mandated for many decades that if someone committed a crime, legally or morally, they were invariably punished for their transgressions.

Griffin doesn’t just escape jail time for his crime, he also gets the girl of the man he murdered, as well as a movie that looks destined to be a blockbuster on account of its slavish devotion to Hollywood formula. The only down note is the intimation that the screenwriter who had been sending Griffin angry postcards throughout the film may be blackmailing him in order to green light his latest script, a dark thriller about a studio executive who kills a screenwriter. The title? The Player, of course. Murder, calculation, and compromise are all rewarded; artistic integrity is punished. Forget it, Jake. It’s Hollywood.

Today it feels like Altman made The Player for Hollywood as much as he made it about Hollywood. The film ironically fulfills many of the requirements of a mainstream commercial movie, while self-consciously calling attention to movie conventions at the same time.

Altman’s big comeback is one of the safest and most conventional films in his filmography. So perhaps it’s not surprising, or coincidental, that this is the film that made Altman a player again. With The Player, Altman made a moderately scathing indictment of the cowardice and groupthink that characterizes Hollywood decision making. More importantly, as far as studios were concerned, Altman proved that he could make a conventionally entertaining and commercially successful Hollywood movie, happy ending, stars up the wazoo and all.

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin