Luke Cage, Black Panther, and Why Heroes of Color Matter

RT columnist and lifelong comics fan Tshaka Armstrong explains why it's important for everyone to see themselves in their onscreen heroes.

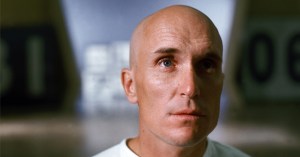

Mike Colter as Luke Cage

In 1939 and 1940, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark conducted a series of tests to study black children’s attitudes about race; they became known as the Kenneth and Mamie Clark doll experiments. If you are unfamiliar, the study demonstrated that, when given a black and a white doll to play with, black children consistently picked white dolls as the “beautiful” ones, or the dolls who were “good,” with the black dolls being “bad.” Positive sentiment was consistently biased toward the white dolls. That hasn’t changed much, even 70 years later. News outlets and various organizations have replicated these experiments with similar results in the last decade. Representation matters.

Nichelle Nichols, Joe Morton, Louis Gossett Jr., Billy Dee Williams, LeVar Burton, Wesley Snipes, Gina Torres, Anthony Mackie, Viola Davis, Laurence Fishburne, John Boyega, and others have delivered stellar performances that defied stereotypes in various sci-fi, fantasy/adventure, or superhero films — but outside of Star Trek, The Matrix, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the lack of breakout roles in major motion pictures has long left persons of color with few aspirational characters to admire onscreen. However, the tide is turning, and my sons may now have more choices than I once had.

Why is this important when we’ve had successful shows with black leads or casts like The Wire, Empire, and How To Get Away With Murder? Simple: it’s mythology. Good vs. evil. Superheroes and fantasy often mirror our highest ideals for who we might become if we’re virtuous in the face of some overwhelming circumstance. These stories represent our versions of King Arthur, Odysseus, Hercules, and Tarzan.

This year I had the unmitigated joy of watching some of my favorite fictional heroes come to life. They weren’t jiving, they weren’t “the muscle,” they weren’t completely hot-tempered and angry at the world, they weren’t just sidekicks standing in the shadows. They were fully realized characters, with depth and dignity. They were power under control, the embodiment of strength, tempered by wisdom or humility. I was able see the fullness of my ethnicity brought to life onscreen in T’Challa of Wakanda, a.k.a. the Black Panther, and Luke Cage, a.k.a. Power Man.

Frequently in film and in the media, black men and women in America have been painted in one light, with one brush. Since the first actor who played a slave, a servant, or a pimp, many of us nerdy types never could have imagined seeing our heroes onscreen as multi-dimensional human beings who were more than just slick, slang-talkin’ jive turkeys or “magical negroes.” Sure, Luke Cage sees its title character channeling some of the badassery of 1970s blaxploitation heroes like John Shaft, but under the vision and guidance of showrunner Cheo Hodari Coker, Cage’s swagger isn’t some puffed-up false bravado written from the perspective of someone unfamiliar with the culture.

Mahershala Ali as Cottonmouth

Cage and all of the characters in Netflix’s new series are complex. Mahershala Ali’s Cornell “Cottonmouth” Stokes will go down as one of the best Marvel villains to date. Then there’s Detective Misty Knight (Simone Missick) and nurse Claire Temple (Rosario Dawson), two fierce sistas who hold their own with powerful performances among a powerful cast of characters. Fiyah!

The show even triumphantly tackles “the N word” with compelling monologues delivered by Cage and his nemesis Cottonmouth, explaining why any thinking human being would or would not want to be called a “nigga.” You may not agree with either’s take, but it’s hard to disagree with their reasoning. In short, the show eschews the simplicity of a media-derived monolithic black culture, illuminating the variety and diversity of thought and affect present in any ethnic group. There is no hive mind in the streets of Luke Cage‘s Harlem, but there is a sense of empowerment. We’re not blindsided by the need for outside help to make our ‘hood better. There’s no cultural appropriation. Cage is Harlem’s hero — Harlem’s answer to Harlem’s problems — and that sense of empowerment is profoundly important if we’re going to change the mental bondage revealed in the Kenneth and Mamie doll studies.

Empowerment is one of the aspects of Captain America: Civil War that delighted my soul. During the end credits sequence, Captain America thanked T’Challa for housing Bucky and cautioned him about what the potential backlash could be for doing so, saying, “If they find out you have him, they will come for you.” As the camera panned out to the giant Black Panther statue overlooking Wakanda’s capital and T’Challa said, “Then let them come,” I damn near shed a tear. T’Challa and Wakanda are not worried about America. They’re not concerned about what S.H.I.E.L.D. might do. They don’t require the permission of American or European governments to operate in their own sovereignty, protecting their own interests. There’s no need for acceptance or assimilation. That is power. That is freedom. At our core, that’s what we all want. The power to be free, not the illusion of such.

Children who look at toys and subconsciously dislike themselves aren’t mentally free, and media plays a significant role in that. My sons, your sons, need to see Christopher Reeves, Steve McQueens, and Rocky Balboas that look like them. Our daughters need to see Julia Robertses, Dame Judy Denches, and Elizabeth Taylors that look like they do. Our daughters deserve to see characters like Cage‘s Misty Knight, or Panther‘s Dora Milaje. As Cage showrunner Coker said, “America is ready for a bulletproof black man” — now more than ever. Whether we like it or not, our fantasies, our symbols, have meanings that speak to our souls. The characters make a statement about our own humanity and we see pieces of ourselves in them.

Chadwick Boseman as Black Panther

It’s kind of ironic as I reflect on what Civil War meant to me in light of the fact that one of the first trailers we watched before the movie was for Tarzan — an old story that leans on a Western cultural trope that the European man must dominate and save wild Africa. A prolific cliché used throughout American media. A notion that flies in the face of persons of color having the power to be free because, ultimately, we need someone else to fly in and oppress — ahem, I mean save — us. I’m thankful that my father raised me with a very powerful sense of my cultural heritage — kind of hard not to do with the name Tshaka — and when I watched the brief Civil War exchange between T’Chaka and T’Challa, all the dad feels hit me. All the old school respect for one’s elders hit me. The impact of what this fictional creation represents, and its significance to young boys and girls of color, hit me. This is needed. This is important.

Often, what children see, they want to be. What they are most inundated with shapes their worldview, for better or for worse. And, ultimately that’s what seeing powerful images of blackness, or Asian-ness (Ghost in the Shell‘s missed opportunity), or any ethnicity, is all about. A sense of power, of confidence. If you’re of Scottish descent, how did you feel the first time you watched William Wallace fight for freedom in Braveheart? I never heard anyone complain about Rocky Balboa’s sense of cultural pride. He was the Italian Stallion, and audiences fell in love with the story regardless. Never once have I heard it referred to as “that Italian movie” the way movies with black leads or casts are often referred to as “black movies.” Let that sink in for a moment.

This is basic anthropology.

Representation matters, and until we see more frequent and diverse stories featuring people of color in sci-fi/adventure, fantasy and superhero roles on the big and small screens, our stories — which are just human stories — will continue to be just “black stories” to much of America, and those doll experiments will continue to produce similar results.

Tshaka Armstrong is a huge nerd and activist who also writes for foxla.com and his own site, tshakaexplainsitall.com, where he talks about food, bearding properly, tech, family, and equality.

Follow Tshaka on Twitter: @tshakaarmstrong