How Sylvester Stallone Transformed Demolition Man from a Subversive Satire into a Sylvester Stallone Movie

Nathan Rabin looks back at a prescient sci-fi action flick whose potential for incisive cultural commentary was undone by the presence of its biggest star.

The story of how a struggling young actor named Sylvester Stallone refused to sell the script to Rocky for a small fortune unless he was cast in the lead is a cherished piece of Hollywood mythology. But Stallone’s subsequent unwillingness to delegate authority or compromise for the sake of someone else’s vision has made his more troubled films cautionary warnings about the dangers of actorly egos run amok rather than the show-biz fairy tale of Rocky.

Though he is an Academy Award-nominated thespian, Stallone isn’t really an actor. He’s not a chameleon who slips inside the minds of sharply different characters so much as he makes the same damn film, playing the same damn character, over and over again. In the past 11 years, he played Rocky in 2006’s Rocky Balboa and then reprised the role in last year’s Creed. He’s also played Barney Ross, a mercenary with a heart of gold, in three The Expendables extravaganzas and resurrected the role of shattered warrior Rambo in the 2008 film of the same name.

Before Stallone experienced a revival by revisiting his best-loved characters, he stumbled through the 1980s and 1990s with projects like 1993’s Demolition Man, which radiated extraordinary promise as a smart, subversive, and loopy meta-meditation on violence in pop culture and the excesses of what was then known as political correctness, co-written by Daniel Waters of Heathers and Batman Returns fame. Then Stallone signed on and the movie became, by default, a Sylvester Stallone movie, and much of that promise vanished instantly.

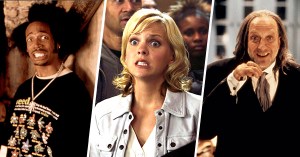

After the requisite set-piece in a futuristic 1996 where Stallone’s glowering super-cop Sergeant John Spartan (even his name screams “scowling block of granite”) tangles with crazy-haired Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes), Demolition Man does something bold: it leaves Stallone’s protagonist offscreen for close to half an hour so that it can build out the future world of 2032 that is alternately utopian and dystopian. It’s a mellow and groovy yet sinister place where everything looks as airbrushed, soothing, and aesthetically pleasing as one of those Silicon Valley campuses with complementary Starbucks on every floor and mandatory hot cocoa breaks.

|

Demolition Man projects the political correctness of the early 1990s onto the future. |

Demolition Man projects the political correctness of the early 1990s onto the future, along with the long-forgotten sense that technology would lead to a cyber-utopia where gizmos would solve all our problems, leaving us simply to kick back and enjoy paradise. In the future of Demolition Man, actual violence is a thing of the distant past, to the point where the only place our villain can track down a gun is in a museum. As a warden played by Andre Gregory (of My Dinner With Andre super-fame) stammers when things begin to go wrong, “Things don’t happen anymore! We’ve taken care of all that!”

Alcohol, caffeine, contact sports, meat, and even spicy foods have been eliminated, along with anything that’s bad for you. It’s life with no violent trauma but also no excitement, a pleasantly, gently tranquilized world with no rough edges, no grit, no grime, none of what historically has made life interesting and made people feel alive. Lieutenant Lenina Huxley (Sandra Bullock in her finest moment as an actor, Oscar or no Oscar), is an odd duck in this world where everyone is disconcertingly content and maddeningly devoid of rage.

Huxley fetishizes the violence and craziness of the 20th century. In one of the film’s many meta-touches, she has the poster for the mismatched buddy cop movie Lethal Weapon 3 (a recent production of Demolition Man super-producer Joel Silver) in an office she has transformed into a shrine to the violent impulses the future was supposed to cure. Yet Huxley worships old-school violence and discord in an incongruously sunny way. She’s Pollyanna with a badge, an endlessly chipper woman overjoyed to engage in such gloriously geeky pursuits as lustily singing along to the Armour hot dog jingle (in Demolition Man, commercials and TV theme songs seem to have replaced most pop music) with the same deranged joy that Wayne and company bring to “Bohemian Rhapsody” in Wayne’s World and Derek and his pals bring to “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” in Zoolander. She also enjoys fancy dinners at Taco Bell, the best, worst, most expensive, and only chain restaurant in the film’s world following the “franchise wars.”

In Demolition Man, Huxley and her colleagues communicate like hippie versions of the Coneheads. In her overly technical brain, sex is a “fluid transfer activity.” She is forever spouting adorable futuristic Spoonerisms, like when she brags, “Looks like there’s a new shepherd in town.”

In the defrosted John Spartan, Huxley has an opportunity to interact with a bona fide relic of the era she grew up worshiping, a true Neanderthal. Demolition Man toys with action movie archetypes, with the idea that what we’re watching isn’t a confrontation between two specific men but the eternal battle between good and evil, cops and robbers, the good guy and the bad guy.

|

Wesley Snipes plays Simon Phoenix as a rampaging id, a lunatic who’s half Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth and half Afro-Punk Little Richard. |

On an iconic level, I can see where it would make sense to cast someone as inextricably associated with onscreen violence and toxic hyper-masculinity as Stallone. The role affords Stallone a tantalizing opportunity to engage in self-parody, to send up the violent brute he’s played throughout his career.

Unfortunately, Stallone himself doesn’t seem capable of intentional self-parody; it’s something he stumbles into by accident, not part of his repertoire as a performer. Also, I’m not entirely sure Stallone realized Demolition Man was a comedy, as opposed to a dour science-fiction movie with some comedic elements. So instead of making John Spartan a dizzyingly over-the-top parody of his usual super-cop, the way he accidentally did in Tango & Cash or Cobra, he instead delivers the usual Stallone performance, only slightly more tongue-in-cheek.

The main problem with Demolition Man is that Stallone is acting in a different film than everyone else. While Bullock is charming her way through an outrageous sci-fi satire overflowing with inspired, memorable ideas (even if they’re not particularly cohesive), Stallone continually drags the film down with a brooding, tone-deaf, semi-dramatic performance as a man out of time who has lost everything but is forced to muster the strength to realize his destiny as a crime-fighter all the same.

In another context, Stallone’s eagerness to explore the emotional complexities of his character might have paid dividends, or even made sense. Demolition Man, however, is a crazy comedy about a testosterone-poisoned macho man who wakes up in a surreal PC uto-/dystopia where swearing is illegal and Taco Bell is the only restaurant, so that he can hunt down a deranged, intriguingly effeminate mass murderer who looks like Dennis Rodman cos-playing Chuckie from Child’s Play. Considering the nature of the movie, his decision to play it mostly straight and phone in the comic elements, effectively doubling down on the angst, feels perversely wrong. It all but single-handedly ruins the film.

Snipes’ flamboyant performance, on the other hand, suits the film far better. He plays Simon Phoenix as a rampaging id, a lunatic who’s half Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth and half Afro-Punk Little Richard. Unleashed in the future, Phoenix is a wolf in a world that’s all henhouses, all victims, all targets for his nihilistic rage.

The reborn Phoenix (Demolition Man is not subtle about the symbolism of its names; clearly at least one of its many screenwriters went to college) is tasked with killing resistance leader Edgar Friendly, played by Denis Leary in an intensely painful, fruitless yet self-aggrandizing exercise in self-parody. Friendly is supposed to be a scuzzy, futuristic amalgamation of Che Guevara and Lenny Bruce, angrily defending our right to smoke cigarettes and eat giant steaks and drive gas-guzzling cars. Instead, it feels like the most profound, incendiary rhetoric the filmmakers could conceive for their uto-/dystopia is two minutes of Leary ripping off Bill Hicks in a bad bit of scenery chewing.

|

Stallone himself doesn’t seem capable of intentional self-parody; it’s something he stumbles into by accident, not part of his repertoire as a performer. |

After an often hilarious first act, Demolition Man gets progressively less interesting and more formulaic as it moves away from giddy social social satire and devotes way too much time to a plot that finds Simon Phoenix acting as a sleeper agent for robed guru Doctor Raymond Cocteau (Nigel Hawthorne), the architect behind the soul-crushing harmony of the future, as well as John Spartan’s emotional arc.

Late in the film, in a line that poignantly hints at the scathing satire that might have been, Phoenix tells Cocteau, “You can’t take away people’s rights to be assholes.” So much of our current culture war and political division comes down to just this issue: Americans’ inalienable, god-given, constitutional right to be as big an asshole as their heart desires, versus the increasingly unpopular notion that while, yes, people certainly do have the right to be assholes, they should strive not to be, both for their own sake and for the sake of society.

Simon Phoenix nails the overall vibe of the future when he describes it as a “Pussy-whipped Brady Bunch version of itself run by a bunch of robed sissies.” Demolition Man depicts the future as emasculated, neutered, and desperately in need of the de-civilizing touch of a man like John Spartan, or even Simon Phoenix, for that matter. Phoenix may run amok and rack up the body count of a small war, but he really livens things up. In our country and our culture, that’s valued to an unhealthy degree.

The culture war that Demolition Man impishly — if unevenly — chronicles has only increased in ferocity in the decades since Demolition Man. Hell, a huge part of our online culture is devoted to an army of trolls realizing with all their might their inalienable right to be assholes. The world remains split between people who want life to be as devoid of trauma and conflict and upset as possible, and are willing to go to extremes to realize that vision, and people who delight in the division, craziness, and unpredictability of existence, and see attempts to tame that craziness as an assault on their basic freedom and concept of the world.

In the past decade we’ve remade beloved cult classics like Robocop and Total Recall despite the originals being nearly impossible to improve upon. In that respect, Demolition Man is exactly the kind of movie people should remake. It’s got a fantastic premise, as well as some wonderful scenes, ideas, and characters, but it is dragged down by a fatal central flaw in its dour lead performance.

Re-watching Demolition Man, I found myself wishing Stallone’s old Tango & Cash buddy Kurt Russell were in the lead (now there is a man with a light touch and a natural flair for comedy), but if they were to reboot the film today, I think Chris Pratt would be good for the role, or maybe Dwayne Johnson. Needless to say, one key to a Demolition Man reboot would involve keeping Stallone as far away from it as possible, though given the nature of his career, I’m guessing this is one role he’d be happy never to revisit.

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin