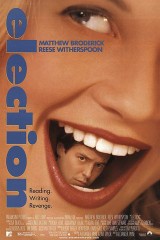

Five Reasons Why Election Is Still a Perfect Comedy, 20 Years Later

Alexander Payne’s razor-sharp, high school-set satire, which opened on April 23, 1999, is still as fresh and as relevant as ever.

Released halfway through what many argue is the best year in film history, Election didn’t exactly set the box-office ablaze after it debuted on April 23, 1999 — the $25 million-budgeted movie made a mere $17.2 during its run. And while critics for the most part went gaga for it — Election is Certified Fresh at 92% — compared to other class-of-’99 highlights, it’s almost easy to understand the general public’s collective confusion about it: It’s not a technological game-changer like The Matrix (88%), not a Best Picture conversation piece like American Beauty (88%), not an ambitiously sprawling drama like Magnolia, not a dorm-room philosophical manifesto like Fight Club (79%), and, even with its high-school setting, not quite what first pops into mind when we talk about ’90s teen movies (despite being co-produced by MTV).

Director Alexander Payne and writing partner Jim Taylor’s follow-up to their abortion satire Citizen Ruth (80%) is not a tidy sell. The comedy, which follows an idealistic teacher (Matthew Broderick) hell bent on making sure one particularly ambitious student (Reese Witherspoon) loses the school’s presidential election, is decidedly dark yet laugh-out-loud funny and paced at a fun, confident clip. So how good is it, with the benefit of two decades’ worth of hindsight? Let us count the ways.

Its Script Is Better Than the Book It Was Based on (and That’s Saying Something)

Before his novels were adapted into big-deal film and TV projects (Little Children, The Leftovers), a then-unemployed Tom Perrotta, obsessed with the one-two punch of the Anita Hill hearings and the 1992 U.S. Presidential election, cooked up a brisk, very funny page turner in response. Election’s narrative setup, in which each chapter is told from the perspective of a different character, couldn’t have been easy to sell on the big screen. Yet Payne and Taylor stick to it, economically and tidily introducing each main player (Broderck’s Mr. M., Witherspoon’s Flick, Chris Klein’s smiley jock Paul Metzler, Jessica Campbell’s nihilistic Tammy Metzler), usually doing something embarrassing. (See: the freeze frame of Witherspoon’s unbecoming expression.)

Speaking of embarrassing, Payne and Taylor’s script consistently strips away any empathy for these characters that the book had, pointing out that most of the people onscreen are essentially trash. (Just count the number of shots of refuse, or when it’s used as a major plot point). Similarly, the duo cook up new scenes, like Mr. M. being stung in the eye by a bee (humiliating) or the re-shot ending, in which — spoiler alert! — the now-disgraced teacher doesn’t have a sort of heart-to-heart with Flick as he does in the novel, but instead chucks a soda (trash again) at her limo when he spots her in D.C.

The Casting Is Ace, with Breakthroughs, Debuts, and One Indelible Character

(Photo by Paramount courtesy Everett Collection)

After her turns in Fear and Cruel Intentions, Witherspoon was keen to go full-comedy, initially hoping to play Tammy Metzler, the screw-it-all sister of popular football star Paul Metzler who makes waves as a last-minute candidate in her school’s student council election, running against her brother. But she was convinced to take on the role of Tracy Flick instead — and thank god for that. Beyond critical hosannas from the likes of Roger Ebert and a much-deserved Best Actress nom at the Golden Globes, the young actor displays a deft comedic sensibility and range (not to mention a killer, energetic midwestern accent) that raises Tracy Flick to icon status. In the following decade, that performance would influence Tina Fey’s impersonation of Sarah Palin, and Dan Harmon said Flick was the inspiration for Annie Edison on Community.

Then there’s Flick’s nemesis, Mr. M., the most popular and beloved teacher at school. At first, Perrotta didn’t think Broderick would work for the role. But, like he proved three years earlier in The Cable Guy, the actor’s sensitive, soft-spoken demeanor is the perfect comedic foil, and as his life starts spiraling out of control (an extramarital affair here, an election sabotage there), his aww-shucks, nice-guy shell makes the whole mess he creates that much funnier.

Although his role wasn’t as demanding as Witherspoon’s or Broderick’s, Chris Klein also shouldn’t get short shrift. Payne discovered the high school senior when he was scouting locals in Omaha, and in his onscreen debut as the sidelined quarterback-cum-student body hopeful Paul Metzler, Klein amps up the dumbness, walking around the halls with a smile plastered on his face like a clueless kid. That summer, Klein would go on to co-star in American Pie, which did 14 times the box-office business of Election and made him something of a teen-movie celeb.

It Somehow Tackles Taboos and Maintains Its Comic Levity

“Her p—y gets so wet.”

“F–k me, Mr. M.”

Both of those lines are in reference to Tracy. (We know. Yikes.) The first one comes from Tracy’s math teacher, Mr. Novotny (Mark Harelik), who drops the description while admitting his affair to Mr. M. The second is from “Tracy,” during a fantasy Mr. M. has while having sex with his wife. (Garbage, remember?) Payne impressively keeps the film lively and buoyant, even when delving into these dark depths, not letting anyone off the hook morally or taking a tonal left turn.

The nastiness doesn’t stop there. Later, in a delightful bit of verbal sparring, Mr. M. brings up the affair, to which Tracy spits back, “I don’t know what you’re referring to, but maybe if certain older, wiser people hadn’t acted like such little babies and gotten so mushy, then everything would be OK… and I think certain older people, like you and your colleague, shouldn’t be leching after their students, especially when some of them can’t even get their own wives pregnant.” Broderick’s stunned, I’ve-been-bested-by-a-pupil face that follows is priceless.

It Nails the Hell of High School (and A Certain Slice of the Midwest)

(Photo by Paramount courtesy Everett Collection)

No matter what side of the desk you’re on, high school can be incredibly… boring. Payne captures that monotony throughout Election, with shots of students spacing out until the bell rings and giving half-assed answers when pushed by their teachers. As he nears rock bottom, the once-idealistic Mr. M., record-holder for teacher-of-the-year at his school, gets fed up with the routine, too. “‘Mr.McAllister. Mr.McAllister,’” he says, in a voice mocking a whiny student. “‘Can I get an A? Can I get a recommendation? Can I? Can I?’ F–k them.”

The midwest — or, more accurately, Payne’s hometown of Omaha, where the film takes place — isn’t spared, either. Chain restaurants playing depressing pop, cheap cars with dirt-smudged windshields, hyperbolically polite parents, and frosty, grey-skied mornings paint a picture of a very specific mediocrity. (The director also explores his native state, and similar dark-comedic waters, in Citizen Ruth, About Schmidt, Downsizing and, yes, Nebraska.)

It’s Still Politically Relevant

We don’t want to get political here (this is a safe space, people), but can you talk about Election without bringing up, you know, elections? Beyond the aforementioned inspiration for Perrotta’s book, Witherspoon’s turn as Tracy Flick has drawn comparisons to too many real-world politicians to mention over the years. (Hillary Clinton, hands down, is the most referenced, and Payne claims Barack Obama told him Election was his favorite political film.) But it does say something about the film’s longevity (or maybe mankind’s predictability) that critics saw plenty of Election in the most recent U.S. Presidential face-off. Same as it ever was.

Election opened in limited release April 23, 1999