Alright, Alright, Alright: Why Dazed and Confused Is More Than Just a Stoner Comedy

Richard Linklater's strange brew of small-town rituals and pop-culture ephemera is a seminal work of 1990s indie cinema.

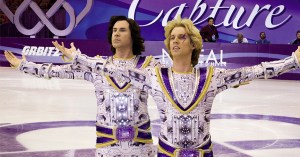

The job of advertising is to make whatever’s being sold seem far better than it actually is. The marketing team for Dazed & Confused took a different approach. Instead of trying to sell Richard Linklater’s follow-up to Slacker as the grunge era’s American Graffiti — a fizzy little pop concoction about kids driving around, listening to music, and trying to get drunk and laid that also just happened to be great art — the film was sold as a generic stoner comedy solely of interest to the already stoned.

The ads for Dazed & Confused, one of the best movies ever made about young people, posited it as a lowbrow comedy with nothing to offer but wink-wink, nudge-nudge references to pot and sexy young actors in tight denim blazing reefer cigarettes while listening to K-Tel’s Super Hits of the 70s. They took something instantly iconic and special and made it seem vulgar, tacky, and cheap.

Yet within the drunk, stoned, sexed-up misadventures of a group of high schoolers and high schoolers-to-be, Dazed & Confused finds a microcosm of American society. It’s no coincidence that the film takes place in 1976 during the Bicentennial, a high-water mark for mandatory/pointless patriotism.

With great humanity and humor, Dazed & Confused observes the sadistic rituals of a class of graduating seniors (and a super-senior played by Ben Affleck) intent on treating a class of incoming freshmen to the same ritualistic, paddling-heavy abuse they were subjected to. The film depicts a casual culture clash between people deeply indebted to the accepted, traditional way of doing things, no matter how insane, cruel, and arbitrary they might seem, and people who question why we must do what we’ve always done, particularly when it seems insane, cruel, and arbitrary.

|

The ads posited it as a lowbrow comedy with nothing but wink-wink, nudge-nudge references to pot and sexy young actors in tight denim. |

It’s worth noting that even the angsty, conflicted characters here don’t actively rebel against the school and town’s customs. Adam Goldberg‘s Mike Newhouse and Anthony Rapp’s Tony Olson, the two most non-conformist characters in the movie, don’t actually try to keep girls from being actively humiliated or boys from being physically assaulted. Hell, they even play along with these brutal games by flirting with a nymphet forced to propose marriage by one of the senior girls.

Everyone seems content to go along with these strange customs out of some combination of inertia, tradition, and peer pressure, or maybe just because they genuinely believe, as some of us do, that getting humiliated by mean girls or beaten up for no good reason is essential to coming of age in America. And for many of us (myself included), it’s not just a component of coming of age, it’s the whole process in its entirety, so there’s something weirdly cathartic and empowering about being able to laugh at the amount of sadism we happily accept at that age.

There’s a wonderful moment that links the petty savagery of high school to the greater horrors of the outside world when the incoming freshmen appeal to their teacher to help them avoid an almost-certain beating by older teenagers. Rather than taking pity on his students, the teacher licks his chops before lovingly quoting a superior from his time in the military who told his men that some of them would not be coming home from their mission, except in a body bag. There is no reprieve from this pain and pointless punishment, only the opportunity to endure it with dignity and grace.

Aside from the ritualistic cruelty, there are other ubiquitous forces that bring everyone together in the film, like the universal high school desires to get drunk, get high, and get laid — preferably in that order — and, of course, the music. It’s hard to overstate the importance of music in the film, just as it’s difficult to overstate the importance of music in the lives of American teenagers. Like American Graffiti, Dazed & Confused feels like a musical even thought it’s not. Music isn’t just the soundtrack to these kids’ lives: it is their lives. It’s how they define themselves, and it’s also a common language they share; they’re united by Peter Frampton’s talk box and the songs on the radio that everyone knows by heart.

It’s especially remarkable how these characters were able to relate to each other this way, since pop culture was infinitely more difficult to access at the time than it is now. In a throwaway bit of dialogue, stoners discuss in reverential terms an almost assuredly apocryphal tale of an hour-long Jon Bonham solo, an epic feat of musical aggression too intense to be processed on strong acid. It’s a moment that succinctly and amusingly captures the way that myths and fantasies about musicians spread in a pre-internet era as a form of contemporary folklore. If that story were to be passed between a couple of stoners in today’s world, one of them would be able to instantly check their iPhone and discover either that it was bogus or, alternately, that there was a Wikipedia entry for it, a Youtube clip seen millions of times, and at least one podcast devoted to the feat.

|

Dazed & Confused feels like a musical even thought it’s not. |

Similarly, there’s a moment of great prescience when the bored kids spend their final moments in class thinking up the premises of as many episodes of Gilligan’s Island as possible. They’re like an analog version of Wikipedia, acquiring and dispensing pointless yet weirdly addictive information in real time. The collection of this seemingly random, almost impressively inconsequential information conveys how the monoculture of the pre-internet, pre-VCR era bound people together, how watching the same dumb shows and listening to the same inane music connected them to each other and to the past.

But there’s a second component to the Gilligan’s Island discussion that indelibly marks Dazed & Confused as part of the same wave of chatty, self-referential cinema that spawned Reservoir Dogs, Clerks, and Go Fish. The girls don’t just aggressively remember one of the most unforgettably forgettable shows of all time; one of them re-contextualizes this quintessential schlock as a male sexual fantasy in which a group of unimpressive men are left on a desert island with a pair of popular American male sexual fantasies: the glamorous, voluptuous movie star sex bomb in the style of Marilyn Monroe/Jayne Mansfield (that would be Ginger) and the girl-next-door type with a nice ass (Mary Anne).

Dazed & Confused is utterly distinctive, but introducing a cozily familiar pop culture reference — specifically from the 1970s, when both the filmmakers and much of the audience were impressionable kids — and then having characters dissect and deconstruct the secret or hidden meaning of that reference, feels akin to what Kevin Smith and Quentin Tarantino were doing at the time.

Linklater’s masterpiece flits easily and organically from clique to clique as they celebrate the final day of class and the promise of a fresh summer, and pursue the easy pleasures and sordid delights that have been the cornerstones of American teenaged life since its inception. The stoners (most notably Matthew McConaughey in his star-making performance), jocks, brains, and freaks are all distinct cliques, but there’s a surprising amount of overlap and blurring as they try to figure out, on an hour-by-hour basis, who they are and what they want.

There are times when the older girls “break” and reveal themselves to be nice people, not the instruments of the universe’s unfathomable cruelty they feel obligated to pretend to be. Of the boys, Randall “Pink” Floyd, a promising and popular quarterback played by Jason London, has the toughest time forcing himself to be an abusive creep. He takes incoming freshman Mitch (an adorably doe-like Wiley Wiggins) under his wing and spares him from further ass-paddling. Despite being one of the film’s less charismatic characters, Floyd’s ethical conundrum is central to the film’s conclusion.

Floyd is torn between roles, loyalties, and cliques. He’s part stoner, part rebel, and part jock, but his hard-ass coach wants him to sign a pledge that he will be exactly who his coach, his parents, and his community want him to be, an exemplar of Christian morality who will not drink, use drugs, or have sex out of a desire not to shame his community or football team.

|

Dazed & Confused is at once bracingly dark and life-affirmingly light. |

It’s a completely bogus pledge, of course. There’s no way it could be enforced, unless the coach dispatched detectives to shadow his team’s every move. Yet on a symbolic level, the pledge gives Floyd something clear-cut to rebel against. The pledge is the ultimate symbol of cowardly, nonsensical deference to arbitrary authority. In that respect, it’s just a little too tidy, but the quietly transcendent scenes leading up to it more than excuse its neatness.

Late in the film, bully and horndog Don (Sasha Jenson), one of the least profound characters, dispenses some of the movie’s most casually profound wisdom. Though he’s spent most of the film aggressively chasing sex and violence in the grossest possible way, he speaks profoundly to the existential problem of high school when he says, “All I’m saying is that I want to look back and say that I did the best I could while I was stuck in this place. Had as much fun as I could while I was stuck in this place. Played as hard as I could while I was stuck in this place. Dogged as many girls as I could while I was stuck in this place.”

Don could be any of us, simply doing the best we can while we’re stuck in this place. In his own accidentally incisive way, he gets to the heart of the American experience. Don realizes that high school is just one of a series of systems and institutions in our culture designed to ground people down and reduce them to automatons. Yet he realizes that, even within the brutal nature of our society and its constructs, it’s possible — even imperative — to steal joy and pleasure wherever you can.

Dazed & Confused is at once bracingly dark and life-affirmingly light. It acknowledges that our society and its institutions are often brutal, dehumanizing, cruel, and, perhaps worst of all, seemingly unchangeable. Yet it still finds abundant pleasure, humor, and light in our perhaps doomed quest for freedom and autonomy. We may not attain self-actualization or change the world, but if we’re lucky, we can score some primo Aerosmith tickets and sneak a few doobies into the show for a little attitude-adjusting, if necessary.

And that, friends, renders Dazed & Confused just a little bit better than the generic stoner comedy its cynical marketing made it out to be.

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin