(Photo by Paramount. SHUTTER ISLAND.)

Pick any decade since the 1970s American New Wave, reach in to grab some of the best movies of those years, and chances are you’ll be pulling out some Martin Scorsese pictures. Along with Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola, Scorsese was among the rabble-rousers who shook filmmaking to its core in the 1970s, when all conventional wisdom (and filming permits) were thrown out the window for a more dangerous yet personal style of cinema. When you think of that decade, what better captures its grit, grime, and freewheeling cynicism than Taxi Driver?

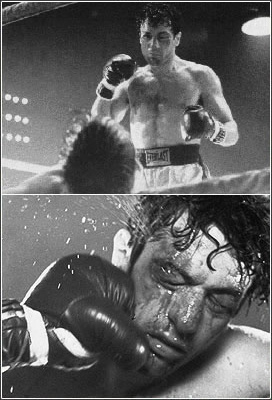

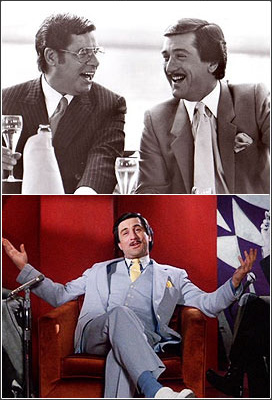

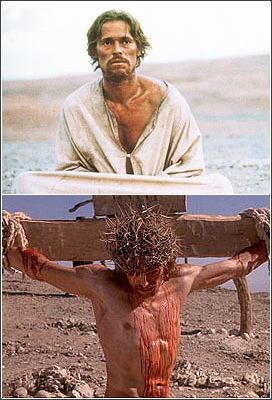

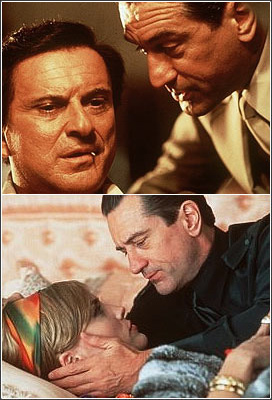

He made the 1980s a wash for other directors by releasing his masterpiece as early as possible in the decade, with the transformative Raging Bull, netting star Robert De Niro his second acting Oscar. Scorsese subsequently showed off his lighter side with the media satire The King of Comedy, the Kafka-esque comedy After Hours, and, um, The Last Temptation of Christ. A real knee-slapper!

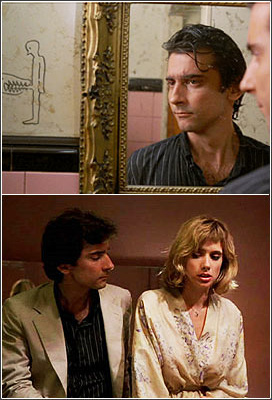

With the 1990s, Scorsese did it again, releasing beloved mob epic Goodfellas in the first year of that decade. While 1995’s Casino works as a companion piece to Goodfellas, Scorsese films also began to have a more specific otherworldly aura, like in the romantic The Age of Innocence and the religious Tibetan biopic Kundun; he then returned to a more hazy, hard-edged spirituality with Bringing Out the Dead, starring Nicolas Cage.

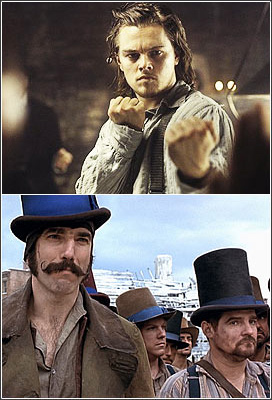

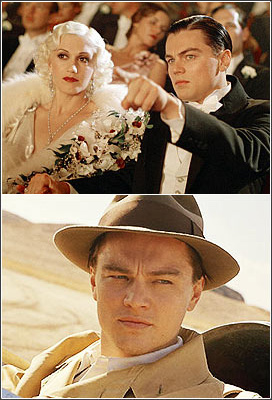

Scorsese’s post-Casino material was not warmly received by audiences, and by the 2000s he was on the lookout for a new actor-collaborator in the same vein as De Niro for a comeback. Scorsese found his man in Leonardo DiCaprio, himself looking to shed his Titanic heartthrob image. Gangs of New York and The Aviator proved Scorsese/DiCaprio was serious business, leading the way for the 2000s masterpiece The Departed, which won Best Picture and, at last, got Scorsese the Best Director Oscar.

The playful Shutter Island, secret movie history lesson Hugo, and the long-gestating Silence were all befitting his reputation and style, but it might be Scorsese’s latest that will be his defining 2010s statement. 2019’s The Irishman arrived into theaters, all three-plus hours of it, on a massive wave of hype for its promise of bringing De Niro, Pacino, and Joe Pesci together on-screen. Judging by the critical response and Netflix positioning the movie as its grand Thanksgiving offering, Irishman did not disappoint.

Scorsese’s latest movie is Killers of the Flower Moon, depicting the 1920s murders of Osage Native Americans over their oil-rich land. With the master director showing no signs of slowing down in his 80s, we pay our respects with our guide to all Martin Scorsese movies ranked by Tomatometer!

(Photo by Orion/ courtesy Everett Collection)

1974 drama Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore is already one hell of a way to jump-start a pre-teen acting career for Jodie Foster, yet it would be her second collaboration with director Martin Scorsese that made her an international star. 1976’s Taxi Driver was a shocking game-changer in a decade full of them, with Foster’s casting as a 12-year-old prostitute eliciting awe and dread from audiences, not to mention an eventual Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress. As a new unlikely industry “It” girl, Foster quickly began to fill her resume with roles equally precocious (Freaky Friday, Bugsy Malone) and dark (The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane) following Taxi Driver.

Foster continued to hone her craft through the ’80s and into the ’90s, receiving a Best Actress Oscar for 1988’s The Accused, and moving on to even bigger Oscar night wins for 1992’s The Silence of the Lambs. 1995’s Nell would be Foster’s last Oscar nom to date, but the Golden Globes have been more receptive: She’s been nominated since for 1997’s Contact, 2007’s The Brave One, 2011’s Carnage, received the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 2013, and finally won another acting Globe with 2021’s The Mauritanian.

More of Foster’s highlights during these decades include David Fincher’s Panic Room, Spike Lee’s Inside Man, and her own directorial-and-starring efforts like Money Monster. And now we take a look at all Jodie Foster movies ranked by Tomatometer! —Alex Vo

Neil Gaiman’s highly-anticipated The Sandman series and the film premiere of vampire actioner Day Shift starring Jamie Foxx, Dave Franco, and Snoop Dogg lead Netflix’s August 2022 offerings.

Of Gaiman’s extensive roster of work, his Sandman comic series is probably his most famous. Now, his iconic tale of Dream (Tom Sturridge) — also known as Lord Morpheus or the King of Dreams — is coming to the streamer. When Dream is captured and held prisoner for a century, the land of the Dreaming is thrown into chaos. He inevitably escapes, though, and finds the realms thrown into chaos. To set things right, Dream embarks on a mission to reclaim his power and meets some interesting characters along the way. Also appearing in the series is Gwendoline Christie as Lucifer Morningstar, Jenna Coleman as Johanna Constantine, Charles Dance as Sir. Roderick Burgess, Boyd Holbrook as The Corinthian, David Thewlis as Dr. John Dee, Patton Oswalt as the voice of Matthew the Raven, and Mark Hamill as the voice of Mervyn Pumpkinhead.

Jamie Foxx stars in Day Shift, a modern-day horror-themed action flick about an international guild of vampire-hunters and the hard-working father struggling to provide a better life for his daughter — by killing the undead for profit. One part From Dusk Till Dawn and one part Blade, the movie co-stars Dave Franco, Snoop Dogg, Karla Souza, and Meagan Good.

Fans of YA fantasy rejoice: the story of the Locke family is finally back with the third and final installment of the hit fantasy series Locke & Key, based on the comic book run by Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez. With more magic being uncovered in Keyhouse, and the most dangerous threat the family has ever encountered let loose, Nina (Darby Stanchfield), Tyler (Connor Jessup), Kinsey (Emilia Jones), and Bode (Jackson Robert Scott) will definitely have their hands full.

For fans of coming-of-age comedies, Maitreyi Ramakrishnan, Poorna Jagannathan, and Darren Barnet return for season 3 of Mindy Kaling’s hit high school series Never Have I Ever. And Kevin Hart joins Mark Wahlberg, Regina Hall, and Jimmy O. Yang in the raucous comedy Me Time.

Find out what else is joining them on Netflix and what’s leaving the service below.

The Sandman: Season 1 (2022)

![]() 88%

88%

Description: After years of imprisonment, Morpheus — the King of Dreams — embarks on a journey across worlds to find what was stolen from him and restore his power.

Premiere Date: August 5

Locke & Key: Season 3 (2022)

![]() 55%

55%

Description: In the thrilling final chapter of the series, the Locke family uncovers more magic as they face a demonic new foe who’s dead-set on possessing the keys.

Premiere Date: August 10

Day Shift (2022)

![]() 57%

57%

Description: Jamie Foxx stars as a hard working blue-collar dad who just wants to provide a good life for his quick-witted daughter, but his mundane San Fernando Valley pool cleaning job is a front for his real source of income, hunting and killing vampires as part of an international Union of vampire hunters.

Premiere Date: August 12

Never Have I Ever: Season 3 (2022)

![]() 92%

92%

Description: Devi and her friends may finally be single no more. But they’re about to learn that relationships come with a lot of self-discovery — and all the drama.

Premiere Date: August 12

Me Time (2022)

![]() 7%

7%

Description: When a stay-at-home dad finds himself with some “me time” for the first time in years while his wife and kids are away, he reconnects with his former best friend for a wild weekend that nearly upends his life. Stars Kevin Hart, Mark Wahlberg, and Regina Hall.

Premiere Date: August 26

Delhi Crime: Season 2*

Partner Track*

Big Tree City*

![]() 33%

28 Days

(2000)

33%

28 Days

(2000)

![]() 76%

8 Mile

(2002)

76%

8 Mile

(2002)

![]() 50%

Above the Rim

(1994)

50%

Above the Rim

(1994)

![]() 37%

Battle: Los Angeles

(2011)

37%

Battle: Los Angeles

(2011)

![]() 78%

Bridget Jones's Baby

(2016)

78%

Bridget Jones's Baby

(2016)

![]() 79%

Bridget Jones's Diary

(2001)

79%

Bridget Jones's Diary

(2001)

![]() 46%

Constantine

(2005)

46%

Constantine

(2005)

![]() 42%

Dinner for Schmucks

(2010)

42%

Dinner for Schmucks

(2010)

![]() 76%

Eyes Wide Shut

(1999)

76%

Eyes Wide Shut

(1999)

![]() 83%

Ferris Bueller's Day Off

(1986)

83%

Ferris Bueller's Day Off

(1986)

![]() 68%

Footloose

(2011)

68%

Footloose

(2011)

![]() 51%

Hardcore Henry

(2015)

51%

Hardcore Henry

(2015)

![]() 61%

Legends of the Fall

(1994)

61%

Legends of the Fall

(1994)

![]() 86%

Love & Basketball

(2000)

86%

Love & Basketball

(2000)

![]() 15%

Made of Honor

(2008)

15%

Made of Honor

(2008)

![]() 91%

Men in Black

(1997)

91%

Men in Black

(1997)

![]() 67%

Men in Black 3

(2012)

67%

Men in Black 3

(2012)

![]() 38%

Men in Black II

(2002)

38%

Men in Black II

(2002)

![]() 42%

Miss Congeniality

(2000)

42%

Miss Congeniality

(2000)

![]() 19%

Monster-in-Law

(2005)

19%

Monster-in-Law

(2005)

![]() 47%

No Strings Attached

(2011)

47%

No Strings Attached

(2011)

![]() - -

Pawn Stars: Season 13

(2016)

- -

Pawn Stars: Season 13

(2016)

![]() 46%

Squirrels to the Nuts

(2014)

46%

Squirrels to the Nuts

(2014)

![]() 44%

Space Jam

(1996)

44%

Space Jam

(1996)

![]() 90%

Spider-Man

(2002)

90%

Spider-Man

(2002)

![]() 93%

Spider-Man 2

(2004)

93%

Spider-Man 2

(2004)

![]() 63%

Spider-Man 3

(2007)

63%

Spider-Man 3

(2007)

![]() 92%

The Town

(2010)

92%

The Town

(2010)

![]() 58%

Woman in Gold

(2015)

58%

Woman in Gold

(2015)

![]() 77%

Flight

(2012)

77%

Flight

(2012)

Buba*

Clusterf**k: Woodstock ’99*

Don’t Blame Karma!*

Lady Tamara*

KAKEGURUI TWIN*

Super Giant Robot Brothers*

Wedding Season*

![]() 32%

Carter

(2022)

*

32%

Carter

(2022)

*

![]() 32%

Carter

(2022)

*

32%

Carter

(2022)

*

![]() 63%

The Informer

(2019)

63%

The Informer

(2019)

![]() 79%

Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Movie

(2022)

*

79%

Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Movie

(2022)

*

![]() 92%

Skyfall

(2012)

*

92%

Skyfall

(2012)

*

Reclaim*

![]() 67%

Riverdale: Season 6

(2021)

67%

Riverdale: Season 6

(2021)

Code Name: Emperor*

![]() - -

Team Zenko Go: Season 2

(2022)

*

- -

Team Zenko Go: Season 2

(2022)

*

I Just Killed My Dad*

![]() 91%

The Nice Guys

(2016)

91%

The Nice Guys

(2016)

Bank Robbers: The Last Great Heist*

Heartsong*

![]() 14%

Indian Matchmaking: Season 2

(2022)

*

14%

Indian Matchmaking: Season 2

(2022)

*

![]() 88%

Dope

(2015)

88%

Dope

(2015)

![]() - -

DOTA: Dragon's Blood: Book 3

(2022)

*

- -

DOTA: Dragon's Blood: Book 3

(2022)

*

![]() 58%

13: The Musical

(2022)

*

58%

13: The Musical

(2022)

*

![]() - -

Ancient Aliens: Season 4

(2012)

*

- -

Ancient Aliens: Season 4

(2012)

*

![]() 92%

Learn To Swim

(2021)

92%

Learn To Swim

(2021)

High Heat*

Junior Baking Show: Season 6*

![]() 62%

Look Both Ways

(2022)

*

62%

Look Both Ways

(2022)

*

![]() - -

He-Man and the Masters of the Universe

Season 3*

- -

He-Man and the Masters of the Universe

Season 3*

![]() - -

The Cuphead Show!: Season 2

(2022)

Part 2*

- -

The Cuphead Show!: Season 2

(2022)

Part 2*

![]() - -

Glow Up

Season 4*

- -

Glow Up

Season 4*

Fullmetal Alchemist: The Revenge of Scar*

![]() - -

A Cowgirl's Song

(2022)

- -

A Cowgirl's Song

(2022)

![]() - -

Chad & JT Go Deep: Season 1

(2022)

*

- -

Chad & JT Go Deep: Season 1

(2022)

*

Lost Ollie*

Mo*

Queer Eye: Brazil*

Running with the Devil: The Wild World of John McAfee*

Selling The OC*

Under Fire*

Watch Out, We’re Mad*

![]() - -

Angry Birds: Summer Madness

Season 3*

- -

Angry Birds: Summer Madness

Season 3*

![]() 84%

Disobedience

(2017)

84%

Disobedience

(2017)

Under Her Control*

![]() - -

Mighty Express

Season 7*

- -

Mighty Express

Season 7*

![]() - -

I Am a Killer

Season 3*

- -

I Am a Killer

Season 3*

Club América vs Club América*

Family Secrets*

I Came By*

They’ve Gotta Have Us: Season 1

![]() 93%

Screwball

(2018)

93%

Screwball

(2018)

![]() 68%

We Summon the Darkness

(2019)

68%

We Summon the Darkness

(2019)

![]() 14%

Demonic

(2021)

14%

Demonic

(2021)

![]() 30%

The Saint

(1997)

30%

The Saint

(1997)

![]() 81%

Mr. Peabody & Sherman

(2014)

81%

Mr. Peabody & Sherman

(2014)

![]() 16%

Endless Love

(2014)

16%

Endless Love

(2014)

![]() - -

Selfless

(2008)

- -

Selfless

(2008)

![]() 86%

The Conjuring

(2013)

86%

The Conjuring

(2013)

![]() - -

Young & Hungry

Seasons 1-5

- -

Young & Hungry

Seasons 1-5

![]() 36%

The November Man

(2014)

36%

The November Man

(2014)

![]() - -

Celebrity Wheel of Fortune

Seasons 35-37

- -

Celebrity Wheel of Fortune

Seasons 35-37

![]() 89%

Taxi Driver

(1976)

89%

Taxi Driver

(1976)

![]() 68%

The Visit

(2015)

68%

The Visit

(2015)

![]() 87%

Wind River

(2017)

87%

Wind River

(2017)

![]() 96%

In the Line of Fire

(1993)

96%

In the Line of Fire

(1993)

![]() 94%

A Nightmare on Elm Street

(1984)

94%

A Nightmare on Elm Street

(1984)

![]() 14%

A Nightmare on Elm Street

(2010)

14%

A Nightmare on Elm Street

(2010)

![]() 69%

A Very Harold & Kumar Christmas

(2011)

69%

A Very Harold & Kumar Christmas

(2011)

![]() 57%

Crooked House

(2017)

57%

Crooked House

(2017)

![]() 66%

Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy

(2004)

66%

Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy

(2004)

![]() 68%

Cliffhanger

(1993)

68%

Cliffhanger

(1993)

![]() 87%

The Dark Knight Rises

(2012)

87%

The Dark Knight Rises

(2012)

![]() 91%

The Departed

(2006)

91%

The Departed

(2006)

![]() 93%

Goodfellas

(1990)

93%

Goodfellas

(1990)

![]() 10%

Grown Ups

(2010)

10%

Grown Ups

(2010)

![]() 97%

Halloween

(1978)

97%

Halloween

(1978)

![]() 54%

Just Like Heaven

(2005)

54%

Just Like Heaven

(2005)

![]() 82%

Kung Fu Panda 2

(2011)

82%

Kung Fu Panda 2

(2011)

![]() - -

Major Dad

Seasons 1-4

- -

Major Dad

Seasons 1-4

![]() 93%

Mission: Impossible - Ghost Protocol

(2011)

93%

Mission: Impossible - Ghost Protocol

(2011)

![]() 67%

Mission: Impossible

(1996)

67%

Mission: Impossible

(1996)

![]() 58%

Mission: Impossible II

(2000)

58%

Mission: Impossible II

(2000)

![]() 8%

Premonition

(2007)

8%

Premonition

(2007)

![]() 68%

Public Enemies

(2009)

68%

Public Enemies

(2009)

![]() 75%

Rise of the Guardians

(2012)

75%

Rise of the Guardians

(2012)

![]() 45%

Soul Surfer

(2011)

45%

Soul Surfer

(2011)

![]() 72%

Starship Troopers

(1997)

72%

Starship Troopers

(1997)

![]() 88%

Titanic

(1997)

88%

Titanic

(1997)

![]() 48%

We Are Marshall

(2006)

48%

We Are Marshall

(2006)

![]() 31%

Wyatt Earp

(1994)

31%

Wyatt Earp

(1994)

On an Apple device? Follow Rotten Tomatoes on Apple News.

Thumbnail images: Netflix

(Photo by Stephane Cardinale - Corbis/Getty Images)

French-Algerian actor Tahar Rahim first rose to international acclaim with his performance in Jacques Audiard’s 2009 crime thriller A Prophet, which debuted at Cannes to rave reviews and went on to earn an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Film. It wasn’t his first feature film, but it was the one that opened the doors for him to work with an eclectic mix of filmmakers that includes Asghar Farhadi (The Past), Fatih Akin (The Cut), Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Daguerrotype), and Kevin Macdonald (The Eagle).

Rahim’s latest project reunites him with Macdonald for a challenging role in a based-on-true-events drama, The Mauritanian. In it, he plays the titular character, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who was kidnapped from his home country in 2002, transported to the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay, and detained there without being charged with any offense for 14 years before he was ultimately released. The film details not only Slahi’s harrowing experiences at the facility, but also the efforts of ACLU attorney Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster) to afford him due process and the shocking discoveries made by the U.S. government’s own military prosecutor, Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch). Working alongside a star-studded cast that also includes Shailene Woodley and Zachary Levi, Rahim’s standout performance recently earned him a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor.

Rotten Tomatoes had the opportunity to speak with Rahim ahead of the Globes to talk about the new film, describe what it was like to meet and spend time with the real-life Mohamedou Ould Slahi, and drop a wish list of directors he’d love to work with (somebody please get him a meeting with the Safdie brothers). Before that, though, read on for Tahar Rahim’s Five Favorite Films.

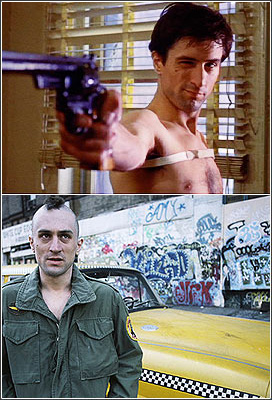

Taxi Driver (1976)

![]() 89%

89%

I’m a big fan of the New Hollywood wave, a very big fan of this period. I think it’s the best period of movies ever. This one is a very specific one because it’s an incredible story of someone who is an antihero. He’s got all the flaws, when you think about it. It can read as a racist, in a way, who could be in love with young girls and totally crazy, who’s trying to kill the president. So he’s got all the flaws, and yet he’s still an ordinary man, you see.

It tells a lot about the way society can create heroes, because at the end of the movie, he’s saving this young girl from evil, from the streets of New York. He wants to clean the streets of New York; that’s his obsession. He finally does it, but you don’t know if he does it for him, for her, whatever. He does it. He quenched his thirst for violence. At the end of the movie, he turned out to be an American hero. It’s crazy what it tells about the media, about society.

And the performances are stellar. The movie is incredible, the way it’s shot. We get to see New York in the ’70s. Because I always say that movies are testimonies for the next generations when they’re well-made classics like this one. When I discovered it — I might have been 17 or 18 — and I could tell my friends what New York looked like in the ’70s. It was right. It was true. They were in the streets, shooting people, the random people who were walking in the streets and buildings and cars and the way they would talk. The whole thing blew me away.

Plus, the script is incredible, the way it’s written. You know, it’s this new period that that looks like a little bit of the New Wave in France. They met the concept of going out there to film reality and people. The way the New Hollywood turned it, it’s better for me, because they weren’t afraid to create antiheroes, to write bigger stories, and to make an x-ray of American society.

I could talk about this movie for hours. You know, the first time I discovered Jodie Foster starting her career; she was absolutely awesome. And of course, Robert De Niro, who stays the best actor ever for me, to me. The ’70s, in a way, they created some codes of acting that never moved from there.

Scarecrow (1973)

![]() 77%

77%

Number two, still New Hollywood. It’s Scarecrow by Jerry Schatzberg. I love what we call here in French kind of a… I don’t know if it’s the same expression in America, but buddy movies. But in this one, I remember when I first watched it, there’s this opening with this road, empty road, windy, and two guys who are hitchhiking, and they’re waiting for someone to pick them up. What’s happening is they talk without a single word. This might be the most beautiful encounter of two characters I’ve seen.

At this moment, they don’t even talk. There’s not a lot of action, but you can tell who’s who, what type of character they are, their identities, in a way. You see Gene Hackman is grumpy. He doesn’t really want to watch him. You can feel that he is ready to jump on him and beat him. The other one’s trying to just, in a way, find a father. That’s sort of the whole movie, to me. He’s trying to make him laugh, using his own skills, all he’s got to communicate. To go from The Godfather to this character, Al Pacino, it’s crazy what he’s doing in this movie. It’s the opposite of The Godfather.

At some point, they start a story together. I remember that they walk through life, and yeah, they have a purpose and they’re going to help each other. It’s about being dependent on someone, but in a good way, because they became friends. I think that Al Pacino’s character is looking for a father. He’s very interesting, but he’s still a kid. He’s a kid that has to be an adult, because he’s got a son, and he’s going to meet him for the first time. He doesn’t know what to do. He just bought a present that he keeps with him all the way along. The poetry of this present is amazing.

The ending, when he finally meets his ex-wife and sees his son, and she’s like, “You’re not going to tell him that you’re his daddy.” She starts to ruin him. You see a mother being rude with her kid. That’s where he fell into despair, into madness. The arc of his character is sad, but incredible.

The 400 Blows (1959)

![]() 99%

99%

I think in English it’s 400 Blows. What an incredible movie. Classic. I mean, I saw it a long time ago when I was a kid. It was beautiful. I liked it, but I didn’t really know what it was talking about. Then I watched it again 10 years ago. When you put it back in its context in the ’60s or ’70s — I don’t know exactly — it’s so brand new. Watching a kid wandering in the streets of Paris and making his own 400 blows, and being a young adult. It was pretty amazing. It brought me back to my childhood. It felt good to watch this movie.

And it tells a lot about French society at that time — working class people; how a relationship between a man and a woman was, in a way; what people know, but don’t say, between the lines. There’s a lot of this in this movie, between the mom and the son and the dad and the son. It’s incredible. I loved it. There’s this pure innocence in this movie as well. The ending on the beach with fireworks… It’s beautiful.

Memories of Murder (2003)

![]() 95%

95%

What a great movie. I saw it at the video tech, not in a movie theater. I didn’t know what I was about to see. I didn’t expect that this movie would be so good. I remember I discovered Oldboy, and I was like, “Okay, we got real movies over there.” I wanted to know more, and I watched this movie.

It starts like a… You see two detectives that don’t really seem clever, and then the guy from the street, from the big city, is going to meet people from the countryside. The shock, culturally, between those two different roots, in a way, is very interesting. It’s like, “Okay. Whether it’s in America, France, or Korea, it’s kind of the same thing.”

The ending is so unexpected. I was like, “What?” And it’s the first time ever that I saw that in a movie, in a thriller like this. The whole movie is built on this investigation — the structure of the movie, as well — so when you reach the climax, you need an answer, and it doesn’t give you an answer. It’s not meant to have a sequel. But I think it’s so clever to do this. Plus, the movie’s protected by its own true story. They never found the right guy, the perpetrators, the killer.

I remember the cinematography is so good. So good. Do you remember the scene when the cops are arresting the young man, thinking that he’s the killer? The father comes and he’s like, “No, it’s my son. He did nothing.” And they start to fight and there’s the cops and this father and his son being arrested, and it’s all in slow motion, except for the sound; the sound runs normally, which is incredible. You’re like, “Oh, it’s the first time I see it.” Usually it’s slow motion music, silence. Now you’ve got the slow motion shot, and the sound is a direct sound. People are screaming and you hear them fighting. It’s incredible. Like, “Okay, wow. What a director.” He did that before [David] Fincher.

Also, in this movie, it’s very serious, but at the same time, there’s a comic layer. It’s funny, sometimes. It’s a lot of poetry.

The Truman Show (1998)

![]() 94%

94%

The Truman Show, Peter Weir, because man, it was ahead of its time, like crazy. I think this movie came out in the ’90s, 10 or 15 years before social media, before reality shows. I mean, that’s so avant garde. He understood so many things, Peter Weir, about the world at that time, what would be the outcome. If you just watch it again, for example, tonight or tomorrow, whatever, you’re going to go crazy. You’re going to go like, “Okay. I mean, did he time travel?”

Plus, you see the innocence of Jim Carrey, who’s got an amazing part, and see his deception. It’s kind of a coming-of-age movie as well, in a way. He’s a kid, very innocent. At some point, he’s going to have to get to the real life, life of adults. No more fantasy, no more lies. It’s just the cruelty of the world.

(Photo by ©STX Entertainment)

Ryan Fujitani for Rotten Tomatoes: The Mauritanian is not the first time you’ve portrayed a real person on film. Do you find that it’s more freeing to play a character based on a real person because you have a template to follow? Or do you enjoy more getting to collaborate and infuse a fictional character with your own ideas?

Tahar Rahim: I think right now, I’d say it’s, in a way, easier to portray someone who is a real life character, because the range of liberty you have is limited. They don’t go all over the place. The main answers you need to know for questions about your character, you have them. And you don’t have them in 100 pages, you have them from someone who’s been living for years, decades, so he knows exactly what he’s talking about. You don’t even have to, “No, you know, I think the character would answer this way.” You don’t have any conversation about who the guy is. He is who he is. It helps a lot.

But on the other hand, the problem is that you have a responsibility to not, in a way — let’s use this word, and I don’t know if it’s the right one — but to not betray that person and his identity and his personality, his life, what he’s been through. You still have some freedom because he’s not a famous person, but not a lot. I don’t know if it feels better to play someone who’s a real life character or just a character. I don’t know if it feels better because it’s a whole thing. It’s not just about a performance, it’s about your relationship with your partners, with the director, the story, the script, and the whole thing.

Rotten Tomatoes: I know you met Mohamedou Ould Salahi before you shot the film. Was there anything about him that surprised you, or anything unexpected about him? Something you were able to work into your performance?

Rahim: I knew about him because I read the book, I talked with [director Kevin Macdonald], I had his recordings. So I had enough materials to make my research. But I needed to meet him for other reasons, to know him and to understand the way he moves, he talks, whatever. But I was so surprised to see how funny the guy was. Everybody would say it, but I couldn’t expect that he would be that funny, because sometimes he was sarcastic, sometimes just funny. That surprised me a lot.

But you know, it was not just a joke. He likes to joke around. But instantly he can find a good joke that is connected to the context. It’s not just written jokes; he’s taking advantage of the situation and turning it into something funny. You need to be very talented to be able to do that, because it’s like improvisation. It’s like asking a comedian on stage to improvise. They need to improvise between their jokes, the things that are written. It’s a real job. This guy has it naturally.

But also, the fact that he was full of life, full of life. Very nice. When you know what he’s been through, it’s almost impossible to believe. The trauma is still there; he manages in some ways to control it, so you don’t see it.

(Photo by Graham Bartholomew/©STX Entertainment)

Rotten Tomatoes: This is a difficult role for anyone, and I would ask how you would normally decompress or de-stress during shooting, but you’ve said that you basically didn’t, because you were afraid you would lose everything you had put into the character. Doesn’t that take a bit of a toll on you?

Rahim: Of course, of course. But I was lucky to shoot that abroad, to shoot this movie abroad. I was alone, with just one of my best friends. Otherwise, if this movie was shot in Paris and I had to see my family and my wife, my kids every day, it wouldn’t have been possible to portray Mohamedou the way I… to give my all.

I got really lucky. I didn’t want to be disturbed. It’s such a difficult part that once I caught him, I didn’t want to let him go. I know myself. I’m almost 40; I know if I start to get relaxed too much, I’m getting out of my character, and then to get back in, it’s hard.

Rotten Tomatoes: You obviously take your work very seriously, and you’ve been able to work with a wide variety of filmmakers from all kinds of backgrounds across different genres to build a really eclectic resume. But you’ve also expressed in the past that there are some Hollywood directors you’d love to work with. If you had to name the top three on your wish list, who would they be?

Rahim: Of course, Martin Scorsese. Paul Thomas Anderson. Who else? There’s so many great directors. I’d say [Alejandro González] Iñárritu. You know what? from the new generation, definitely the Safdie brothers.

Rotten Tomatoes: I could absolutely see you in a Safdie brothers movie.

Rahim: You know, Good Time was a beautiful surprise. I was like, “Oh, man!” You can feel the New Hollywood references, but it’s not copying. It’s not about that. They’re talking about their time, the people they met, their life, their New York, and it’s incredible. It reminded me of New Hollywood, without copying them. I found it so clever and so brand new, in a way, in the way they shot, in the way they direct their actors, and the last film they did, Uncut Gems, the last 13 minutes… It’s like a James Brown concert. It’s like James Brown saying, “We’re going to shake them. Shake them ’til the end.” I was like, “Whoa. Okay, these guys are great.”

The Mauritanian was released on February 12, 2021.

Thumbnail images: Everett Collection, ©Neon

On an Apple device? Follow Rotten Tomatoes on Apple News.

(Photo by Niko Tavernise / © Warner Bros. / courtesy Everett Collection)

Joker: The highest-grossing R-rated movie ever at over $1 billion in worldwide box office, and also the most nominated movie at the 2020 Oscars. Not bad for a comic-book flick from the man who gave us three Hangovers. If you’re looking for more movies like Joker, the obvious place to start would be its direct influences: The Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese psychotic joints, Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy. Throw in ’90s Cape Fear for a full triumvirate.

As you’re undoubtedly aware, Joker was not universally beloved by critics as far as Joaquin Phoenix vigilantism flicks go (though those who loved it, loved it). For that, turn to Lynne Ramsay’s Certified Fresh You Were Never Really Here, where Phoenix plays a fearless hired gun who tracks down missing girls at any cost. And if you like your lawless justice even grubbier, go with the Charles Bronson action classic Death Wish, or the churning slow burn of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs.

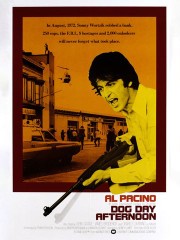

Beyond Scorsese, Joker director Todd Phillips has cited post-Vietnam War ’70s cinema in general as an influence, and that decade had no shortage of man-against-the-system stories. Look upon One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network for proof.

Network also serves (and so does Dog Day honestly) as an indictment of media, a major and pervasive presence in Joker. Nightcrawler, Natural Born Killers, and Christine (not the one about the scary car) are the ones to watch if that’s where your interest in Joker lies.

Or if you’re just interested in seeing psychotic breakdowns, or breakdowns of psychosis, the medium of movies have long been a playground for the disturbed. American Psycho, Entertainment, and One Hour Photo go for the jugular, while The Vanishing, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, and Man Bites Dog truly try to get under your skin with their clinical explorations of madness.

Of course, Joker is still a story torn from the pages of DC Comics and in that vein we recommend checking out Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker. It’s got Mark Hamill reprising his signature villain role, animated at his most intensely violent. (Ah, if only The Killing Joke adaptation were good!)

And as for our suggestion of UHF, “Weird Al” Yankovic’s foray into film spoofery… Imagine a world where Arthur Fleck actually achieved success in his professional ambitions. What would that look like? We think it’d be a little zany, a little weird, a little something like what the clown prince of music offers in his 1989 cult classic. —Alex Vo

(Photo by Rotten Tomatoes)

One of Hideo Kojima’s most resonant achievements in his 30-year career as a video game designer and director came early. Kojima saved a troubled project at Konami called Metal Gear by reducing the game’s combat and emphasizing avoiding detection, pioneering the stealth genre. When it was ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System, it sold over a million copies in America.

Kojima returned to the series in 1998 with Metal Gear Solid for the PlayStation, a groundbreaking hybrid of intense stealth action dressed with stylish cinematic flair that went on to move six million units. He designed and directed four more direct Metal Gear sequels, piecing together a complex and occasionally bizarre tale of nanotechnology, nuclear proliferation, military conspiracies, and, yes, love blooming on the battlefield that has found wide appeal beyond core gamers.

That explains the cast Kojima was able to put together for his latest game, Death Stranding. Through motion capture, Norman Reedus stars as as Sam Bridges, a cargo carrier tasked with connecting a post-apocalyptic America back online, outpost by outpost. Reedus is joined by Lea Seydoux, Mads Mikkelsen, Margaret Qualley, Lindsay Wagner, Guillermo del Toro, and Nicolas Winding Refn in an audacious boots-on-the-ground epic, which emphasizes collaboration with other players online over violent shootouts in rebuilding America, featuring Kojima’s signature maximalist storytelling.

He’s always worn his inspirations in the open, and the way they weave into his games is part of their crossover charm and fun. You can get a sense of what movies Kojima watches through playing his games: Blade Runner is all over cyberpunk graphic adventure Snatcher, there’s plenty of Escape From New York‘s DNA in Metal Gear Solid, and Death Stranding even has a major character named Die-Hardman. So when Kojima stopped by for a tour of Rotten Tomatoes HQ on the eve of The Game Awards — where Death Stranding won Best Game Direction, Best Score/Music, and Best Performance (Mads Mikkelsen) — we had to sneak in a Five Favorite Films.

It’s like a monolith to me, that movie. Every time it’s re-shown in theaters, I always go. Star Wars was a big hit in 1977 which created a big sci-fi boom. So 2001 came to Japan, and I saw it in theaters when I was in middle school. Before experiencing that, I was just listening to radio dramas. I read the original novel, but the movie was totally different. I didn’t really understand it the first time. Now, I have a different interpretation every time I watch it. As a creator, I have periods of difficult times, but whenever I feel particularly in need of a pick-me-up, I watch 2001. It’s a perfect movie for me.

It was a real space experience. Exploration even before man went to the moon. I always wanted to be an astronaut when I was a kid, but Japan doesn’t have NASA. You had to go either to USSR or China. Although I felt like I had to give up on the dream of becoming an astronaut, when I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, I felt like I really went to outer space. It’s a life-changing movie because it made me feel like I accomplished a dream.

Did you see Christopher Nolan’s 70mm restoration of 2001 last year? Did your interpretation of it change?

Yes, I went to see it with my son. I was more interested about what my son would think. It seems it was quite shocking for him, like something he has never seen or experienced before. Something not really predictable. It’s really difficult to find something that’s created by man which is unpredictable. These days it’s all set.

Taxi Driver. Martin Scorsese. Growing up, most of my friends were interested in becoming bankers or working in a company. I, however, wanted to become a movie director. This was something that I couldn’t be open about with my friends and oftentimes I felt lonely because I couldn’t share those aspirations. I lost my father when I was quite young. My mother was working and I was a latchkey child. Even if I talked to a lot of people, I always felt a little lonely. I thought maybe I’m sick, maybe I’m ill. There was no counseling, or there were no therapists. It was not a trend at that time. So I thought maybe I’m really strange.

After watching Taxi Driver and seeing Travis, I felt this immense similarity between the character and myself. He lives in New York, surrounded by so many people, but he still felt lonely. This surprised me, and I thought “Here is this guy, living in America, who is like me.” Seeing his character, I felt relaxed and realized there are others like me. I felt I was okay.

And I wanted to put that feeling in Death Stranding. Like, you’re all alone, trying to connect the world. Everything has been connected by the internet recently. In so many ways, everyone is battling each over the internet. If you play online, you get head shots, but, like, you don’t know who you actually shot, right? To connect is a very positive concept. But there are people who don’t want to feel connected anymore, and I think a lot of people play games that don’t offer human connection. I can’t tell anyone that I feel lonely or I’m in solitude, and I have this big problem which I couldn’t share with my friends. It’s a big load to carry, just like Sam Bridges. And you’re kind of traveling, you’re sent orders, you go to this place, you trip over, and drown in a river.

But at one point, you have this indirect connection system where you know you’re not alone. It’s not an isolated, lonely planet. There is someone who creates a road. There is someone who has made the coffee. It’s not just me, and I wanted to put that in a game. This is the same feeling I got from Taxi Driver.

Mad Max. George Miller is my ultimate mentor. I went to see Fury Road 17 times in the cinemas.

I can’t really express in one word of how good Mad Max 2 is. There’s hardly any dialogue in that movie, right? But the character stands out so much, visually, how he moves. Usually, you express through dialogue, but with George, it’s totally different. Like how a character throws a boomerang: No dialogue, but all character. I’m also influenced by where Geroge places the camera. It never goes away, far from Mel Gibson. Even looking through the telescope, usually the camera jumps to that location, but here you’re always looking at Max. It’s kind of basic, but George Miller keeps it basic in a way no one else can.

It was tough when I had to leave my previous company. George came to Japan, and that was the first time we met. He cheered me up in my darkest time. After I became independent, and opened my studio, I went to Australia in 2017. I had two trailers at that time, but there was no gameplay revealed yet of Death Stranding. I explained what Death Stranding would be over an hour — the system, the story, the world. George told me, “What you’re doing is mathematically, philosophically, and physically correct.” He said: “Congratulations; it’s a guaranteed success.”

George is a very kind gentleman. He is really into computer graphics and technology, and he also knows game technology. It’s really rare that a director of his generation knows all of these. He’s even older than me, but he has a lot of energy. There are game producers who are much older than me. But, as for creators who actually write scenarios or game designs, I think I’m the oldest in the industry. Sometimes I feel lonely because of that. But then there’s George; he’s over 70, and he’s still wearing this leather jacket, still young. That cheers me up.

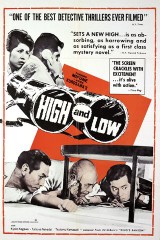

Stanley Kubrick, Hitchcock, Kurosawa: My father always showed me these directors’ movies, whether I liked it or not. I’m selecting Kurosawa’s High and Low because it’s a little different.

It’s based on a story by Ed McBain, and it’s about a kidnapping. During those times in Japan, if you kidnapped someone, you weren’t penalized too much. To have a harsher sentence, other charges, like drugs, were needed. But because of High and Low, the law in Japan changed. The movie had made a positive impact in society. That’s my kind of wish when I create a game. I think entertainment has that power to change society. You don’t have to be a politician or run for a cause to create change. High and Low was, in that sense, really impactful.

Entertainment isn’t really just entertainment. It leaves something in people’s hearts and that person might be moved to create something. It’s a push for that person the next day, and I think entertainment should be similar, including games. When you experience something, and then come back to the real world, I want people to feel a little influence in their world.

When it was first released, I was in university. I went to see it alone. In Japan, it only showed for two weeks. There were probably similar reactions in America after its release.

Nowadays, it’s regarded as a classic, but when it was first revealed, there was a lot of criticism. Maybe Death Stranding is the same [laughs]. When Blade Runner was shown for the first time in movie theaters, it was totally different from other movies. The rhythm of how it begins and all, that’s why it catches my eyes. It’s something that’s really indigestible in the beginning and stays in me. Then we moved on to the home video era, where you can watch videos over and over in your room. In the cinemas, you see it once and it’s over. Anything else that’s not digestible and that you can’t relate to, will be criticized. But for videos, it’s different. You can watch it over and over until you digest it yourself. Blade Runner might at one time be perceived only as a “cult movie,” but turned mainstream from the ability to watch it over and over and allow the viewers to digest the content. So Blade Runner was ahead of its time for the current generation at its release.

Ghost in the Shell was probably the same, because it was on video where people watched it over and over. It got really popular; everyone got it. I deliberately made the tempo of Death Stranding totally different than the current games out there. So it might not be for everyone. Blade Runner showed in the cinemas, but then it changed when it came to video. Same with games. We have a platform, we have a console, and then in the future, it will be all streaming. Everything, storytelling, and the rhythm of how you play games will totally change in the near future.

Alex Vo for Rotten Tomatoes: You also made headlines recently because Kojima Productions is moving into the movie space. What can you tell us about the process so far?

Hideo Kojima: I’ve already started kind of, yes, but I can’t really announce it yet. Games are primary for Kojima Productions. Of course, I have staff that need to work. We create games, and maybe in-between… We’re an indie company, so maybe something really punkish in a very small team sort of way, we do a smaller game, and we might do some short films too.

I get a lot of offers, but I’m not really free all the time. If I do 100% movies, the staff will have nothing to do for the other projects, right? So I am doing all these things, but eventually think games and movies will all be on streaming platforms. I could just shoot normal movies and maybe that could be one project I could do. But I think other than that, doing something on a streaming platform and doing something new that no one has done before is more interesting to me.

Thumbnail image: Warner Bros., Columbia Pictures

Death Stranding is currently available for PlayStation 4.

(Photo by Jeff Kravitz/Getty Images)

After a breakout year in 2018, actor/writer/director Alex Wolff looks to finish 2019 on a wave of momentum and stellar reviews; while poised to make 2020 even more spectacular. While collecting innumerous accolades and an impressive box office haul for his starring role in Ari Aster’s Hereditary opposite Toni ‘was-robbed-of-an-Oscar-and-we’re-still-not-over-it‘ Collette, Wolff simultaneously watched the receipts roll in for his the end-of-year smash hit Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle (he will also return for the sequel Jumanji: The Next Level this December). Our new “Crown Prince” of the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival, the veteran actor trekked to Toronto with not one or two but three Fresh features, including the HBO pickup Bad Education starring Hugh Jackman.

Just days away from his 22nd birthday (yes, you read that correctly — twenty-two — and no, we can’t wrap our heads around it either), Wolff will soon hit theaters both in front of and behind the camera for his feature debut, The Cat and the Moon. In the film, we follow Nick (Wolff), a teen who explores the streets and dark jazz rooms of New York City with a friend of his late father after his mother unexpectedly abandons him to enter rehab. We recently caught up with Wolff to chat about his Five Favorite Films (a series he’s a surprising expert about), give him a few recommendations, and find out if acting or directing was his first love.

What don’t I love about Taxi Driver? Taxi Driver is my favorite performance, and it’s my favorite score — Bernard Hermann, man. I was talking to someone today about why it’s the greatest film of all time. It turns this kind of sadistic ticking time bomb of a man who’s falling apart at the seams into this dreamy, seductive, gorgeous portrait of a vulnerable person. It turns all this sadism and all that deep hatred for the world into this empathetic, Holden Caulfield-type, just deeply pained truth. Not even to mention how it ties into today’s isolation. It’s a movie made in the ’70s that’s more relevant now than ever. It’s needed to show how this sort of isolation, this sort of alienation, can lead to rage and vengeance, but can also be used for good. It’s this crazy luck of the draw — Travis Bickle could have gone in either direction. He could have become this horrible man who murders a bunch of innocent people, but then he latches onto the idea that he has to murder all the bad people. I find that to be such a beautiful concept. Not to mention that it’s shot with these gorgeous reds and greens that are so lush. To watch, it’s like chewing a chocolate bar. It just melts in your mouth, that film. It’s everything I love about movies. It’s the smoothest, most velvet, but also the roughest and the deepest pit of despair you could go into. It’s everything. It’s everything in one film.

Are you excited for The Irishman?

So excited. So excited! Little worried about the special effects, though. Actually very worried about the special effects, but excited.

I recently saw it. They’re pretty amazing; I’m not going to lie.

Yeah, I can– Wait! You’ve seen The Irishman?! How was it?!

Al Pacino is a god in all actorly things. Pesci is just as good. I was like, “And the Oscar goes to…” It was so good. So good.

That’s amazing. I’m jealous. I can’t wait.

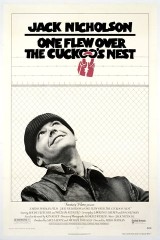

What’s to say about One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest that someone else hasn’t already said? It’s perfect. Milos Forman, wow. It’s the most soulful, most heartfelt movie ever made. It’s hilarious. The most dynamic performances — Jack Nicholson’s just robust persistent optimism in that movie is so infectious. His complete lack of sympathy or empathy for anyone who wants to reject life. That character is something so unique. I don’t know if it’s ever existed in the way that it did in that. Not to mention the whole ensemble of Danny DeVito, Brad [Dourif], everyone in that movie is incredible. I find that it’s got such a sense of humor and such a light touch, but it’s also got such a deep, patient eye. I love it. I absolutely love it. I saw it in theaters the other day and just sobbed. I saw it with my dad, and we were both weeping. It’s such a nice uniting film between many generations. It’s got a universal, timeless quality.

In terms of directing, what he does in that movie is kind of impossible. He has no real scope. He’s in that asylum, and yet it’s this delicious, not bleak movie to watch. All the greens and whites, everything is so pretty. Just the cigarette smoke, and the way he navigates the camera around that area and all the color palette and his choice of shot, it’s really a feat. Only once you’ve made a movie do you see how much you rely on your surroundings and your environment and how I was spoiled because I was shooting in New York on these rooftops. It’s not even fair. I’ve got all these buildings and these lights and these streets and the homeless people and all this crazy, vivid environment. To shoot a movie in one location essentially and make it that lush and interesting; to be fascinating the entire way through without it feeling like a play on wheels. I can’t understand it. I’ve seen it a billion times, and I can’t understand it. Like how is that possible?

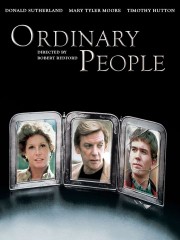

Those performances. Timothy Hutton’s performance in that is probably the most directly inspiring to me, and that’s a young guy at the top of his game, emotionally raw, and brings everything that a young actor could want in a performance. I feel that that film is the most heart-wrenching and true portrait of a family maybe I’ve ever seen. To describe it well would reveal too much. That’s what’s brilliant about it. Everyone should watch it and watch Mary Tyler Moore with Timothy Hutton and Judd Hirsch. I can’t believe it. I just can’t believe that movie. It seems like such a simple concept, and yet Robert Redford kills it.

The scene that always gets me, hits me so hard, is a small scene that not many people would say they love. Most say the big breakdown scene with Judd Hirsh. For me, it’s the scene where Timothy Hutton has been going to Judd Hirsch for a little bit, and he’s opening up. It’s such a journey of what it means to be vulnerable and the importance of vulnerability in your own family, especially after trauma. My character in The Cat and the Moon is very much inspired by Timothy Hutton’s character in Ordinary People. His journey of being so closed off and edgy to cracking open into this well of unmined emotion. Particularly the scene where he and Donald Sutherland, who’s amazing as well, are decorating the tree — ugh, the Christmas tree. It’s such a sweet scene. Mary Tyler Moore comes home, and she’s got this cold, dark look on her face. I’ll never get over her facial expressions in that movie. What she’s thinking versus what she’s putting on the surface is the most genius magic trick. It’s the most exhilarating thing ever. That movie is the best.

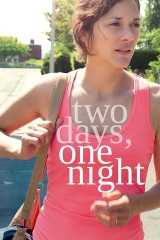

Two Days One Night, it’s perfectly directed. The way the Dardenne brothers frame her, making her kids’ bed before she goes and tries to overdose in the bathroom — it stays in that one shot. It’s this wide shot, handheld, which nobody does like the Dardenne brothers. I’ve tried to chase it; there’s nothing like it. There’s nothing like watching a scene unfold and becoming something you did not expect in the beginning of the shot. It’s like one shot can tell an entire three-course meal. Also, that movie is one of the few movies that made me uncontrollably sob at the end, because of her power, the sweetness of it. I can’t believe the sweetness; it made me so raw and vulnerable. It’s not just that it’s tragic. It’s such a small story, but I connect with it. I connect with needing people and needing for them to hear from you. I feel like getting heard at the end of the movie, or not getting heard, depending on how you look at it, is so unbelievably moving. Marion Cotillard is the god of our generation. Not a goddess, she’s god!

Al Pacino’s performance is connected to something deep in my psyche; he feels like a wild animal trapped in a place and running around manically. I love the mania of Al Pacino’s performance. I feel a connection to that hyper energy and burning ball of rage. It’s so great how he turns the whole movie. He becomes the hero that you wouldn’t expect, and everybody is cheering for him. I love that. I think in my film it does kind of the same thing. He doesn’t seem like your hero, but he becomes that. Not to mention the fact that this movie, it keeps the kinetic thriller energy, but at the same time, there are there these scenes that you can’t believe they’re still going on, these hilarious seemingly improvised bursts of energy. Between Al Pacino and Sidney Lumet and John Cazale, it’s unforgettable and beyond inspiring, to say the least. You’re rooting for both of them even though you don’t want to be. It’s perfect. You fall in love with them, and they fall in love with each other. It’s genius — perfection. I know that’s five but can I have an honorable mention?

This picking five is stressing you out, huh? You’ve read every entry in the series, and know more than anyone else I’ve interviewed, so I will give you an honorable mention. Just don’t tell anyone one.

Okay, Great! All the President’s Men is my honorable mention. The performances are the biggest inspiration in terms of pure realism. It feels like I’m watching a documentary between Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford. That movie, more than any movie in the world, feels like I’m watching a real thing unfold. So bravely un-cinematic, and let me say in the most complimentary of ways, those shots are simple but very nuanced and controlled. The performances are totally free and loose, but you never feel a moment of “drama.” It’s what I look to before I do a movie. Almost always before I act in a movie or before directing a movie, I watch the performances because they feel like reality. That it’s next-level s–t.

Jacqueline Coley for Rotten Tomatoes: You were recently a part of two huge films in the pop-culture consciousness, but they’re completely different: Jumanji and Hereditary. What was that like?

Alex Wolff: That’s a really cool question. There were a couple of other films that I was part of that came out at that time, so I saw it more as a clump of films that I was really proud of. I did House of Tomorrow, then My Friend Dahmer then Jumanji, then Hereditary, and then I started developing my film The Cat and the Moon. Yeah, Hereditary was this crazy overnight thing. I remember prepping to shoot my film, seeing all these articles popping up on people’s phones. Everyone was like, “Hey, your movie is killing at Sundance.” I was like, “Oh, cool.” I don’t think much of it. I’ve been part of enough things that people say are going to hit and then don’t, so who knows what’s going to happen? That one was just crazy, though, because it came out of nowhere, and it just seemed to hit me in the face. Jumanji, it was like a “Phew!” because they put a lot into it, a lot of money, and a lot of people were part of it. I had such a great time doing it, but that was a huge relief; it was well-received. My Friend Dahmer also did way better than people thought. Hereditary was such a challenging and exciting experience. I was so proud of what we did. That’s a long-winded way of say I still haven’t really processed it. It’s kind of crazy. I know that now I can’t walk down the street without people looking at me and knowing my face. I’m like, okay…. okay.

Which one do people on the street mention most?

Easy. Hereditary, and they make the clicking sound. [Laughs] And a lot of people say they hate me and that I traumatized them for life, but I just take that as I’m doing a good job.

The Cat and the Moon is your first feature as director. Was this the goal from the beginning?

Acting was always number one. It’s still number one. It’s the love of my life. It’s the thing that I do. It’s my job and the thing I’m the most obsessed with. I believe that writing, directing, and acting are all part of the same sphere of creativity. They’re all achieving the same thing for me, just in different ways. Writing and directing is this cool way of expressing it. I find that they’re unfortunately separated somehow when people talk about them. We’re all trying to make a great movie. That’s what I love. I love good movies, and I love the artistry around all of it. Writing, directing, and acting, to me, are part of the same world. It’s like you’ve got the tricep and the bicep and the elbow, and it’s all making your arm.

Was there anything that you saw from working with Ari Aster, Cory Finley, or some other director that made you say, “Okay, I want to apply that my directing?”

Yeah. Peter Berg, who’s an executive producer on The Cat and The Moon. Peter Berg and Ari [Aster] and Corey Finley, whom I’ve worked with twice, and all these other amazing directors that I’ve gotten to work with, were fully responsible for easing my nerves. They talked me through what it’s going to be like and what to prepare for. What I learned from them was to have full confidence in what I was trying to make. Ari, Peter, and Cory are all bold filmmakers in their own right and specific filmmakers. They make films that are personal to them. I knew I would hate myself forever if I tried to put in complex steady cam shots, because that’s not what this movie called for. Maybe I’ll do that in the future, but I knew this movie was fully in the heart of the Dardenne brothers. A patient character study that needed the camera to be still and patient to feel like this beautiful eye was watching what was going on. They told me to have full conviction in what it was, what I was doing, and try not to create something that was bulls–t.

As a working actor, was casting the film easier or more difficult, and is your brother in any way mad that you didn’t cast him?

My brother has got enough going on; he was so busy. He helped me produce it, but yeah, he’s really mad. [Laughs] No, I’m just kidding. He is in it, though. You’ll not notice but it’s his voice in the background of a scene. I won’t tell anybody which. We recorded on an iPhone, and we ended up using it because it was so funny. I’m screaming at him on the street.

And the casting?

It was easier than I thought it would be. It was really easy to audition because I was so excited that people were reading my dialogue. I loved seeing them improvise, and that was part of what made me cast them. I cast people who could improvise great stuff. Getting kids or teenagers who can do that is kind of few and far between. For this film, there’s a lot of different types of things that demand personal magic and demand a certain type of spontaneity that can make this type of film work, that if it doesn’t have it, the film falls flat. Most of the people didn’t audition. I knew Tommy Nelson, who plays Russell. He was in the film called My Friend Dahmer with me. Stefania Owen, I’d done Come through the Rye with, and she was amazing. Actually, no, Julian did an audition. I made my friend audition. I’m a terrible person. But it was because I hadn’t seen him in that type of part. Mike Epps, I just offered it to him because I saw him in these two amazing movies. I saw him in this film Bessie and in Sparkle. I thought he was amazing in both of them. I didn’t even remember that I’d seen him in The Hangover — lots of New York actors. There’s a bunch of amazing actors in New York, and everybody brings something really interesting to the table. It was hard choosing honestly.

You said giving a log-line is a bit stressful, so how about you give us the three films you’d recommend to watch before or have same the vibe of your film?

You Can Count on Me, Oasis, and The Kid With a Bike, and maybe Blue is the Warmest Color as an honorable mention.

You love those honorable mentions

Yeah, well I love these movies; it’s so hard to choose.

The Cat and the Moon is in theaters October 25th.

(Photo by Nicholas Hunt/Getty Images)

Ari Aster may not be a name you immediately recognize, but it’s likely one you’ll be seeing a lot more of in the future. The New York native began his career with a handful of short films, most notably 2011’s The Strange Truth about the Johnsons, which touched on themes of sexual abuse and family dysfunction and set off heated discussions in the independent film world.

Last week, he unleashed his first feature-length film, Hereditary, which premiered at Sundance earlier this year to rave reviews and became Certified Fresh upon its release. It’s a tense, slow-burning horror film dressed in the trappings of a family drama, infused with dread and punctuated by shocking moments that are equal parts terrifying and disturbing, and it’s marked Aster as a talent to watch. He spoke with us about his Five Favorite Films, and considering the technical skill on display in Hereditary, it wasn’t surprising to learn that he counts some classics among his influences. Read on for Ari Aster’s Five Favorite Films.

I guess I’ll have to start with Songs from the Second Floor, which is a film by Roy Andersson, who is a brilliant Swedish filmmaker who basically… He made a feature in the ’70s called A Swedish Love Story that is a really wonderful, strange, funny, acerbic commentary on Sweden that became this huge hit. I think it was the biggest hit ever in Sweden. And then he delved into making commercials for a long time, and he developed this new style over the course of something like 300, 400, 500 commercials. Then, in the early 2000s, he came out with this film that took him several years to make called Songs from the Second Floor, which is like a parody of obsessive perfectionism. He’s very similar Jacques Tati in that he works primarily with stationary wide shots, and he’s always building sets. All of the sets in his films are built from scratch, and the reason his films take so long to make is because each each vignette is one shot, and the set for that shot tends to take a month to build.

There’s just like these gorgeous paintings, and there’s this really singular, dark, dry, sad wit driving everything he does. Since Songs from the Second Floor he’s come out with two other films that play like spiritual sequels, You the Living and A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, which I think you can see on Netflix. But Songs from the Second Floor remains the most perfect of the films, in my opinion.

You talk about the way those sets were built, and I’m wondering if that inspired the way you shot Hereditary, considering you built that house on a set as well.

Absolutely. I love working on sets, and I love the artifice of sets that are built on a stage. I’ve always loved playing with artifice in that way, and I really tried to find a way to put a Powell and Pressburger film on this list for that reason, because I just love what they were able to do on stages. For the same reason, that’s why I love Roy Andersson.

I guess the next one would be Fanny & Alexander. I had to put a Bergman on here, and I really struggled to choose between Fanny & Alexander and Cries and Whispers, especially because Cries and Whispers was a film that I screened for the crew of Hereditary. But the television version of Fanny & Alexander, which is five hours long, strikes me as the greatest of the Bergman films. It just has everything. It’s got his humor. It has his sense of wonder and it’s so dreamlike and so gorgeous. The performances are so incredible. It’s so sprawling. Then it gets incredibly bleak when the father dies and the children are shipped off to live with the bishop, who is one of the great forbidding Bergman villains, but that’s just a film I love and adore.

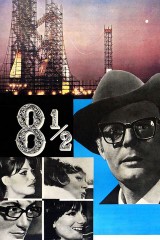

Number three is 8 1/2. I feel like this is not particularly original of me, but this film probably has the most athletic blocking and camerawork that I had seen in any film. A lot of my favorite filmmakers have stolen from this film — you know, the filming from Fellini in general, but especially this film. I’ve already started stealing from him, but filmmakers like Scorsese and Polanski — so much of their technique is derived from really just the playfulness of this film in particular, and whenever I want to inspire myself to play with the camera and to play with blocking and to try to go a little bit further, I’ll watch 8 1/2.

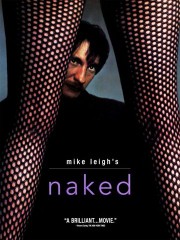

I guess the next one would be Naked, by Mike Leigh. Mike Leigh might be my favorite living filmmaker. A lot has been said about his working method, you know. He spends about six months with his actors basically finding the characters and improvising and building these relationships. Then after that, he’ll go off and write a script based on the improvisations that took place over those six months. It results in some of the most vivid character work I’ve ever seen. The relationships in his films are so rich, and you just feel so much history there. That’s because the history has really been built. It really exists.

But what people don’t really talk much about is just how wonderful a craftsman he is. His films are gorgeous and they’re beautifully made. I mean, his work with Dick Pope is just incredible, and they’re all so impeccably structured. So, I just think he’s made so many masterpieces. I toggled between Naked and Topsy-Turvy and Secrets and Lies being my favorite. But right now, Naked is the one that is coming to me.

I read that you also screened All or Nothing for the Hereditary crew.

I did screen All or Nothing for the crew for Hereditary, which is another film I just adore. It’s one of his bleaker family dramas. It ends on a bittersweet note. It’s a very tender film, but it’s also deeply sorrowful. It struck me as a kind of a perfect movie to watch before we made Hereditary.

My final choice. This is really tough. Part of me wanted to say Dogville. Part of me wanted to say The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. And then part of me wanted to say Rosemary’s Baby. But I realized that I had to put an early Scorsese in there. I had a hard time choosing between Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, but I think it’s got to be Taxi Driver. I mean, from Bernard Hermann’s score to what Scorsese does with the camera with Michael Chapman. Yeah, it’s just like this sickly fever dream that captures a New York that I never got to see, but it just feels like New York to me. You know, the way that he kind of wrangled all of these very important influences that have nothing to do with one another. Like, there’s a lot of Bresson in there, but then there’s also Max Ophüls and there’s Fellini and there’s Cassavetes. You know, you see so many sources, but together they’ve become singularly Scorsese. I could put any number of Scorsese films in here. I could put Raging Bull, Goodfellas, The Age of Innocence, The King of Comedy, but right now this strikes me as like his toughest and most perfect film.

Also, Bernard Hermann’s score is so persistent and so pervasive, it feels like a total montage, because that score is so driving. I’m not sure if there is another Scorsese film whose score is so integral. I mean, Cape Fear‘s score is all over it, but Taxi Driver is like top to bottom just Bernard Hermann music.

Ryan Fujitani for Rotten Tomatoes: I understand that Hereditary was, at least in part, inspired by a difficult time in your own family’s life. Did that make it harder to work on this film, or was it more therapeutic?

Ari Aster: Well, the wonderful thing about the horror genre is that you can take personal feelings and material that’s touchier, and you can push it through this filter, and out comes something else. So, I was able to kind of exorcise certain feelings without actually having to put myself on the slab or put anybody else in my life on the slab.

RT: What film do you think people would be the most surprised to hear was an influence on Hereditary?

Aster: Let me think for just a second. I can say that my prime reference with Pawel Pogorzelski, my cinematographer, as far as lighting was concerned was Kieslowski’s Red. We were talking a lot about Kieslowski’s Red when we were talking lighting, and that kind of become our most important reference, lighting-wise.

Hereditary is playing in theaters everywhere now.

Astrid Stawiarz/Getty Images

Astrid Stawiarz/Getty ImagesThough he’s widely recognizable these days as the current Star Trek franchise‘s “Scotty” and the Mission: Impossible franchise’s IMF technician Benji, Simon Pegg first caught the attention of movie buffs in 2004’s Shaun of the Dead, a zom-com co-starring Nick Frost and directed by Edgar Wright. It was the first in a trilogy of hilarious, wildly clever comedies steeped in pop culture geekery dubbed the Three Flavours Cornetto, and it rightly earned the trio a wider cult following.

Since then, of course, Pegg has branched out and found work in a variety of genres, including the blockbuster series mentioned above, but he likes to keep busy with smaller projects in the meantime. This week, for example, he stars opposite Margot Robbie in Terminal, a stylized crime thriller that interweaves a number of connected stories.

We should note that Simon Pegg has done a Five Favorite Films with us before, and as we began chatting with him about it this time, he admitted that “there are films which have staked their claim in my affection forever. The ones that stay with me and remain my kind of go-to cinematic events, I would imagine, stay the same.” Read on for Simon Pegg’s updated list of Five Favorite Films!

I’d go with the first Star Wars just because that was the source of it all, even though Empire is essentially a slightly more grown-up, often seen as the better film. But I think Star Wars, really as the kind of ground zero, has to be the one. A New Hope, as we’re now supposed to call it after all this sequel bulls—.

Also, I would say probably Taxi Driver, just as a piece of acting and just fabulous scene-setting brilliance from Scorsese and characterization from De Niro. That’s one of those films I just watch in awe of all of it, because it’s just so uncompromising.

I saw Avengers yesterday, and it was such a fun romp and really entertaining and decently done. That’s the kind of film adults watch today, when in the 1970s, when Taxi Driver came out, that was the kind of film that adults would watch. That and French Connection and Godfather and Bonnie and Clyde. Anything pre-Star Wars, really. The preserve of grown-up cinema in those days were genuinely grown-up movies, and that goes for everything I’m doing as well, from Star Trek to Ready Player One or even Mission: Impossible. They’re pure entertainment rather than think pieces, which is what film cinema used to be in the mainstream.

Why do you think that’s happened?

Because of Star Wars. Star Wars happened and spectacle was thrust to the front of the priority list for filmmakers, and as such, we started to change our tastes more toward fantasy and stuff that required big special effects set pieces, and as such, that muscled its way to the front of our affections, I guess. For better or for worse, you know, that’s cinema now.

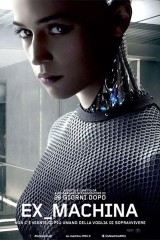

As a piece of modern cinema, I would love to mention Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, which I thought was a brilliant, brilliant film. I think in a year that saw Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson have another science fiction film out as well, it was such a great reminder of how smaller, more thoughtful, more intense, grown-up… It’s an example of the combination of those things, in a way, a kind of more science fiction in the vein of 2001, a more cerebral, literally cerebral kind of science fiction film that was and just how beautifully performed it is. Alicia Vikander is amazing in that film. It’s a film that I’ve watched many times because I just, I don’t seem to tire of it. I think it’s excellent.

It’s a terrific film. Have you had a chance to see Annihilation?

I have, yeah, and I thought it was brilliant, kind of everything that everyone seems to be asking for right now. It’s like, people keep saying we should have more diversity, and there should be more original ideas, and there should be more women in positions and roles where they get to have more power and strength. It was all those things, and yet it didn’t seem to get marketed that well. Not enough people saw it. It was great. It was a really, really smart movie. I love Alex Garland. I think he’s got such great ideas, and he pulls great performances from his actors. I really liked it. Ex Machina — I would probably go with that one just because I’ve known it for longer, so I’m more acquainted with it. I have a greater affection for it because I’ve seen it more.

Let me try and think of a comedy. At university, I wrote about Annie Hall. I know Woody Allen is currently a contentious issue, but that film as a comedy, if we can separate the art from the person for whatever reason, is such a clever, poetic film, but it’s written in the same way that a poem is… When you read a piece of prose, it’s very formal and everything follows one after the other. It’s very conventional. Poetry is different because it draws attention to itself as writing, and it rhymes and does different things, and it uses rhythm. Annie Hall in the same way does that cinematically. It’s kind of like a cinematic poem, and it’s just really, really smartly made. It’s one of the few comedies that ever got nominated or actually won any Oscars.

Comedy, I think, is one of the most underrated art forms that there is, particularly in terms of material rewards. There is no Oscar for best comedy. There is no Oscar for best comic performance. I think that’s a shame, and I think if there was, then Jim Carrey would be laden down with scones. It’s not something everybody can do. You might dismiss Ace Ventura: Pet Detective as a ridiculous, goofy, throwaway movie, but it is a virtuoso performance from Jim Carrey, as often is with his work. You see a lot of so-called straight actors, serious actors, trying to do comedy, and they cannot do it. I think comedy is something which is underestimated because it is literally not serious. It’s like people think that seriousness equals serious, if you know what I mean.

But Annie Hall, I think, it’s such a well-crafted film. It says a lot. Diane Keaton is just unbelievable in that movie. I got to meet her at CinemaCon. She was there promoting Book Club, and I said to the people I was with at CinemaCon, I said, “I have to meet Diane Keaton. Please, can you introduce me to her? I just need to tell her how much I love her. I won’t bother her too much.” I found a moment and I went over and I just told her I had written a thesis about her at university. She said, “Oh, I’d love to read that.” And I said, “No, you wouldn’t. It’s boring and dense.” But she was delightful. For her performance alone, that film, as controversial as it might be, would definitely be on my list.

All right. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’ll pick something completely weird and ridiculous for the very reason that I just said, and that would be Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls, specifically for the scene in which Jim Carrey births himself from the anus of a fake rhino, because it is one of the single most genius pieces of comedic writing that will never be given its due because it’s part of a ridiculous, vaguely racist, silly comedy.