Why John Waters’ Cry-Baby Deserves More Attention

Nathan Rabin attempts to separate the art from the artist while rewatching this oddly touching ode to Eisenhower-era outsiders.

When I first heard that Johnny Depp had been accused of domestic violence against soon-to-be ex-wife Amber Heard, my response was as human as it was idiotic. My brain cried out with clueless fanboy defiance, “No! That can’t be true! Ed Wood would never beat his wife! Edward Scissorhands would only accidentally harm a partner, due to his scissor-hands and whatnot! Cry-Baby would never throw an iPhone in anger (in part because he probably died decades before smartphones were introduced, but still)!”

It was dumb, but it was a natural response. It’s hard to care deeply about pop culture and not be invested in the totality of our favorite artists’ lives, on screen and off. My secondary awful yet human response to the domestic violence allegations was that I found them disturbing, but not as disturbing as they would have been if they’d come out 15 years ago, when Depp was still one of my favorite actors and not mired in bloated, joyless, excessively costumed self-parody.

I’m not proud to have thoughts like that, but it makes sense that we’d be more invested in the lives of artists we admire. If Chet Haze destroyed several entire hotel chains during a coke-and-hooker-heavy rampage that ended in a police shootout, I doubt anyone would be surprised — or care — with the possible exception of his family. Haze is a second-generation entitled baby-man screw-up. That’s what entitled baby-man screw ups do. But if Tom Hanks — beloved American, preeminent pop culture icon, and, to a much lesser extent, Chet Haze’s profoundly embarrassed father — were to do the same thing, I think we’d all be disappointed and horrified. This unexpected orgy of bad behavior would instantly and permanently change Hanks’ reputation for the worst.

Something similar to my initial reaction to the Depp news seems to be at play in the media. Online comments on stories about the divorce and domestic violence accusation are tilted disproportionately in Depp’s favor. Heard is demonized as an evil, scheming gold digger while Depp is defended as the innocent victim of a conscienceless schemer decades younger than him.

|

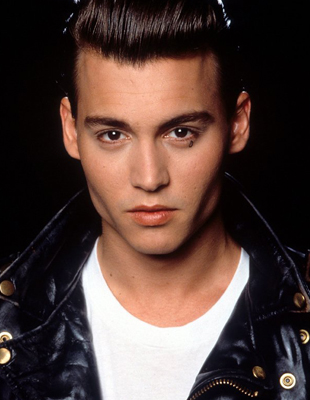

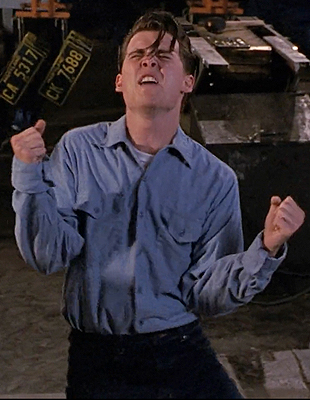

Watching Cry-Baby, you get a sense that Depp had attained a state of perfection that was inherently impossible to sustain. |

It doesn’t help that Heard often plays femme fatale types while Depp has made himself and Disney a fortune playing lovable rogues. Domestic violence doesn’t fit with Depp’s persona, but it’s worth noting that he has had a series of personas over the course of his career. He began as a non-ironic bad boy with a heart of gold and teen idol on 21 Jump Street. Then he segued smartly into satire, independent film, and offbeat choices when he starred in the utterly charming 1990 musical comedy Cry-Baby, John Waters’ loving and eminently re-watchable follow-up to his mainstream breakthrough Hairspray.

I suspect that Depp wouldn’t mind escaping the ugly mess of his personal and professional life and traveling back decades in time to the era of Cry-Baby, when he radiated all the promise in the world. The decades ahead would bring mo’ money, and with it, the requisite mo’ problems, and watching Cry-Baby, you get a sense that Depp had, physically at least, attained a state of perfection that was inherently impossible to sustain.

In Cry-Baby, Depp spoofs his 21 Jump Street persona as Cry-Baby Walker, a pouty-lipped, perfectly cheekboned heartbreaker who rules as the unofficial leader of the Drapes, a contingent of proud juvenile delinquents, outcasts, and ne’er do wells lovingly looked after by Ramona Ricketts (Susan Tyrell) and her partner Belvedere (Iggy Pop). They’re menaces to society, but because this is a John Waters film, they are also a wonderfully diverse and open-minded bunch that includes an African American gent with a towering pompadour, a pregnant woman, a woman nicknamed Hatchet Face for reasons that quickly become apparent, and even a pair of adorable children on hand as pint-sized mascots.

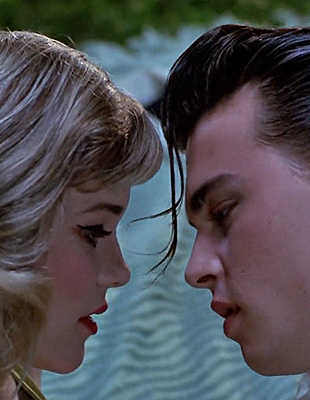

Cry-Baby is relentlessly pursued by Lenora (Kim Webb), a bosomy bad girl intent on ensnaring him in her man-trap, but he only has eyes for Alison Vernon-Williams (Amy Locane), a good girl who undergoes a profound sexual awakening the moment she first sets eyes on him. Cry-Baby may be PG-13, but the smoldering looks Alison shoots Cry-Baby are strictly NC-17, and though Locane is lovely in a role that didn’t do anywhere near as much for her career as it should have, Depp is the one who is relentlessly sexualized, who is treated as eye candy as much as a flesh-and-blood human being. The camera doesn’t just love him; it obsesses over him in a way that would probably result in a restraining order if it were human. And Locane’s character is more than merely attracted to Cry-Baby; he seemingly keeps her in a state of perpetual erotic infatuation — and he does the same for the audience. As Cry-Baby Walker, Depp is sex incarnate, a gorgeous creature who is as pretty as a girl but blessed with a rugged masculinity.

|

In Waters’ world, sex is not dirty or corrupt. Sex is innocent. Sex is joyful. Sex is the essence of being young and alive. |

The film honestly and lovingly captures the hormonal haze of adolescence and the sexual yearning behind so much of our fetishization of 1950s and 1960s greaser culture. Yet in Waters’ world, at least, sex is not dirty or corrupt or even particularly naughty. Sex is innocent. Sex is joyful. Sex is the essence of being young and alive. Cry-Baby is, on some level, an extended riff on Grease, the big difference being that Grease has a reputation as clean-cut, wholesome Americana but is actually incredibly smutty, while Cry-Baby professes to be naughty and ribald but is surprisingly wholesome underneath.

Waters’ affection for the days of his youth is refreshing largely because it is devoid of the maudlin, sentimental phoniness that defines most nostalgia, particularly of the 1950s variety. There’s an underlying sincerity to his yearning for a simpler past as well as an admirable desire to recreate the Eisenhower era in his own idiosyncratic image.

The film epitomizes what makes Waters such a weirdly inclusive and beloved figure. In the eternal battle of the slobs and snobs, Waters’ sympathies will always be with the slobs. Hell, he even gives his greasers and punks and rockabilly no-hopers a veritable wonderland to inhabit in the form of their Turkey Point homestead, which is like Pee-Wee’s Playhouse reimagined as the ultimate greaser hangout. Waters began on the fringes of both film and society, but with Cry-Baby, which was produced by big-timer Brian Grazer and released through his and Ron Howard’s powerhouse Imagine Entertainment, he was given the kind of budget he could only fantasize about in the early days, and he made the most of his resources.

Cry Baby is a quintessential ensemble film. Many of its best moments involve Waters lovingly observing his 1950s bad boys and squares in their natural environment while one of Waters’ beloved half-forgotten oldies makes an unholy racket in the background. The film moves to a ramshackle musical rhythm, and Depp accomplishes the seemingly impossible feat of matching the charisma of Elvis Presley back in his Jailhouse Rock days, when his androgynous sexiness posed an implicit challenge to an uptight nation that was both aroused and confused by the swiveling of his hips.

If Cry-Baby is an extended valentine to juvenile delinquents, greasers, and AIP exploitation movies about teenagers running amok in sinful and titillating ways, it has a sneaky and surprising amount of affection for squares as well. When the preppy boys croon doo-wop classics in casual harmony with big, goofball smiles on their faces, it’s supposed to be ridiculous and hopelessly dorky, particularly when contrasted with the nuclear bomb force of the title character’s sex appeal. But the film takes a distinct pleasure in that squareness, and encourages audiences to do the same.

|

Waters’ affection for the days of his youth is refreshing largely because it is devoid of the maudlin, sentimental phoniness that defines most nostalgia. |

The Squares that the Drapes face off against are white to the point of being translucent. Waters has a lot of mischievous fun creating an over the top burlesque of uptight, gee-whiz retro whiteness. Cry-Baby is the kind of film where the exemplars of cultural conformity giddily Bunny Hop down the street and propriety isn’t just an obsession; it’s damn near a religion, which makes Cry-Baby and his lot heretics.

For a man who began his career in the field of profoundly filthy, X-rated gay provocations, Waters has unexpectedly come to represent childhood innocence. There is a reason he’s become one of the most beloved figures in American culture despite not having made a movie in twelve years. For Waters, naughtiness and innocence are hopelessly intertwined. When Cry-Baby mocks both sides of the 1950s square/greaser divide, it’s from a place of profound understanding and affection.

Is it possible to enjoy Cry-Baby in light of the ugliness of its star’s personal life? For me and my wife at least, the answer is yes. Acting is not autobiography. Though we like to imagine that movie stars are the people they play, acting is the art of pretending to be someone you’re not. If Depp undoubtedly invested elements of himself into his most beloved roles and performances, he is ultimately not Edward Scissorhands or Ed Wood or Captain Jack Sparrow or Cry-Baby Walker. Nope, he’s just the guy who played them. Re-watching Cry-Baby, I found myself falling in love with the film, its title character, and Depp’s performance all over again, even if my affection for the actor has diminished to the point of non-existence in light of Heard’s allegations.

Original Certification: Fresh

Tomatometer: 73 percent

Re-Certification: Fresh

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin