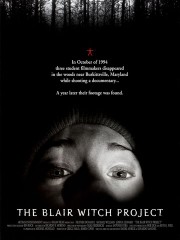

21 Most Memorable Movie Moments: Heather’s Confessional from The Blair Witch Project (1999)

Twenty years after its release, The Blair Witch Project writer-directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez reveal how they worked with Heather Donahue to make movie history... in extreme close-up.

Watch: Writer directors Eduárdo Sanchez and Dan Myrick on the making of The Blair Witch Project above.

In 2019, Rotten Tomatoes turns 21, and to mark the occasion we’re celebrating the 21 Most Memorable Moments from the movies over the last 21 years. In this special video series, we speak to the actors and filmmakers who made those moments happen, revealing behind-the-scenes details of how they came to be and diving deep into why they’ve stuck with us for so long. Once we’ve announced all 21, it will be up to you, the fans, to vote for which is the most memorable moment of all. In this episode of our ‘21 Most Memorable Moments’ series, writers and directors Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick reveal how they worked with Heather Donahue to create one of the 1990s’ most disturbing horror scenes.

VOTE FOR THIS MOMENT IN OUR 21 MOST MEMORABLE MOVIE MOMENTS POLL

The Movie:

The Blair Witch Project introduced a new type – and level – of hype into the entertainment industry, and then lived up to it. Following a storied reception at its premiere at Sundance in January 1999, the ultra low-budget flick was snatched up by distributors Artisan Entertainment and, thanks to the efforts of that company and the filmmakers, rode one of the first ever viral marketing campaigns to become a genuine pop-culture phenomenon. (Remember all those secret screenings and stories about the cast being real-life victims of the witch? We do.) Following its initial limited release on July 14, 1999, the movie would go wide later that month and go on to make $140.5 million dollars at the domestic box office off a budget of $60,000. It would then go on to spur debates about whether it was actually that scary, and kick off a run of “found-footage” imitators seeking to replicate its success. Through the haze of all that history, it can sometimes be hard to remember the details of the film itself: a simple story about three friends – played by Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard – who go into the woods looking to make a documentary about a local Maryland legend, the “Blair Witch.” Here, writer-directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez talk about their initial idea, how they found their cast, and their unique approach to capturing shaky terror in the woods.

Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez. (Photo by © Artisan Entertainment/courtesy Everett Collection)

“Let’s just cut all the documentary stuff. Let’s go with the footage that we shot in Maryland and see what happens.”

Eduardo Sánchez: “We started talking about these other movies that we love like The Legend of Boggy Creek, and Chariots of the Gods, and this show, In Search of…, which was this pseudo-documentary show that was hosted by Leonard Nimoy. We love that show. It scared the crap out of us because it set everything up as being real. (After Blair Witch, we went to their production office, and they told us that a lot of the stuff is made up, which is fine, whatever.) I just remember the terror as a kid, that Bigfoot episode, or the UFO episode of In Search of…, I couldn’t get it out of my mind for months. We went back and said, ‘Is there a way for modern audiences [to see] a fake documentary that hits all these points? Just build this urban legend, and then put people right into it, right in the middle of it?’ In ’96, we started developing it. We were doing a full-length In Search of…episode. We would basically show the footage, give background information on the legend, why they went in, talk to their parents, and then show a little bit of the footage. We went down that road for a while, until the very end of the edit process where we’ve decided that the documentary-style stuff that we had shot was detracting from the drama and the tension and the dread of the found-footage part. It was very late in September, very late in the process. We were about to enter Sundance, about to send the VHS tape in, and we made the decision. We’re like, ‘Let’s just cut all the documentary stuff. Let’s go with the footage that we shot in Maryland and see what happens.’”

“Heather’s audition was just that right blend of naïveté, young enthusiasm, a slightly Geraldo Rivera-esque kind of cluelessness.”

Daniel Myrick: “One of our mandates in the audition process was to find people that were really good with improv. We set up, basically, a scenario that would be similar in experience [to the film] as an audition process. We came up with this idea of a parole hearing where, when the actor came into the audience to sign up, they got a little paragraph handed to them that they’ve been incarcerated for 12 years for murder, now they’re up for parole. State your case, basically. If they weren’t already in character we knew right away that they were dialing it in. That was a quick way as a first level filter to get through people. After literally almost a year of off-and-on auditions – we did auditions in Orlando, we did some in L.A., did a bunch in New York – it finally came down to about 12 or 13 people. Even up to that point we were still thinking that it was going to be three males in the lead roles, but Heather [Donahue] stood out for us. One of the big questions in the audition was why are you here at the parole hearing, and why do you think you should be released. She just turned around and said, ‘I don’t think I should be released.’ She took a completely different take. You have to understand, I had been listening to hundreds of people complain why they were wrongly accused, going into these long dissertations about why they were innocent. She just said, ‘I wasn’t innocent.’ That stood out for me.”

Heather Donahue stood out in auditions. (Photo by © Artisan Entertainment/courtesy Everett Collection)

“On the callback she came back in, and she even took it up another notch, and was just that right blend of naïveté, young enthusiasm, a slightly Geraldo Rivera-esque kind of cluelessness, and smart. One of our big questions, of course, as a documentary is: Why would the camera person continue rolling the camera? There has to be a motivation. It’s sort of an ethical question, I think that war photographers have, and why aren’t you rushing to help. Why aren’t I more concerned about my own life. Why am I still rolling camera? You need somebody that has a kind of personality that you would understand why they would continue shooting themselves. She had that right blend.”

“The underlying mandate was just to roll on everything. Don’t have these moments unless you’re rolling.”

Myrick: “The way we set up the production during shooting was we wanted to be able to control the overall narrative, but also allow the actors a lot of flexibility to kind of explore, and be free to say what they want to say, and allow some of these interpersonal dynamics to evolve a little bit. We had way points, but guided by GPS. All their campsites were marked, so they could navigate through the woods with a GPS without being hindered by a crew. We shadowed them as they were moving through the trees listening to their performances, and then we could also review their tapes. When they came to their checkpoint, they’d put all their spent tapes in there, and we’d give them fresh tapes. We had plastic milk crates [at the campsites], and inside would be foodstuffs, provisions, spare batteries, fresh batteries for the cameras, film for the film camera, and then there would be the old-school 35 millimeter film canisters for SLR cameras. Inside those little plastic containers would be directing notes. So, they would read their directing notes, and they were all instructed to not read each other’s notes. Heather’s note might say something like, ‘You’re going south to get back to the car. No matter what anybody says you know the car is south to the campsite.’ Then a note for Josh would be, ‘You can put up with this s–t for only so long, but sometime this afternoon you’ve got to take control.’ We set up this conflict, but we allowed them to choose the time when they want to have it. Then the underlying mandate was just to roll on everything. Don’t have these moments unless you’re rolling.”

The directions were to keep rolling, no matter what. (Photo by © Artisan Entertainment/courtesy Everett Collection)

“She started following me. I was making noise, and she started coming right at me. It was like this moment of fear for me, like, ‘Holy s–t.'”

Sánchez: “We played the Blair Witch. First of all, we didn’t tell them what we were going to do. I mean, they knew that we were going to f–k with them at night – that was the basic premise. They knew that something was going to happen, and also, they trusted us, and they knew that they were safe. We weren’t going to light the tent on fire or hit them. We would basically lay the whole day out, and then at 12 or 1 AM in the morning we would walk out to their location where they were, and then we would just start. We planned the gag beforehand, whether it was just running around the tent, or making certain noises, snapping twigs. I remember the first night that we were out there scaring them, the first night where they hear the noises, and Heather goes out, and her and Mike have a little fight. She doesn’t want to leave the tent. That scene. She started following me. I was making noise, and she started coming right at me. It was like this moment of fear for me, like, ‘Holy s–t,’ and I remember just running down this hill. You can hear it in the footage. It’s part of some of the noise we used. I felt like she turned the tables on us with that a bit because we didn’t know what she was going to do.”

“They were asleep pretty early because they were hiking all day, very tired. We got there, and then we very quietly placed the boombox right next to the tent, and then you hit play.”

Sánchez: “My mom used to babysit some kids, so the sound recordist, Tony, went over to my mom’s house and just basically recorded a couple … I think there were two brothers just playing, just messing around, and whatever, just doing what kids do. He took that tape, and he put it on a cassette tape, and then we just went out, basically, that night, very quietly. They were asleep pretty early because they were hiking all day, very tired. We got there, and then we very quietly placed the boombox right next to the tent, and then you hit play. Then at a certain point, we shake the tent and they run out. Mike Williams always tells the story of how creepy it was to wake up to little kids playing outside your tent in the middle of the woods. As a human being, it just freaked him the f–k out. It was cool that they were able to get into that mode where they were actually being freaked out.”

The Moment: Heather’s Confessional

The Blair Witch Project, like most memorable horror flicks, has a handful of moments that stick with you for years. There’s the strange twig effigies, and all that shaky-cam running in the woods, and that shiver-inducing final scene, with Mike facing the corner. But by far the movie’s most memorable moment – a viral scene within a viral movie – is the sequence in which Heather, the party’s leader, goes off by herself into the woods to record a confessional. She’s terrified, regretful, and realizes she’s likely going to be responsible not just for her own death, but that of the people with her. It’s been parodied for decades, but rewatch it today and it’s lost none of its power to scare and to move.

Myrick and Sánchez knew they had something special with the scene. (Photo by © Artisan Entertainment/courtesy Everett Collection)

“We just told Heather basically, ‘Now’s the time where you go off into the woods.’”

Myrick: “We knew that [the main character] would be a pretty hard-driving main character who fwould be sort of a composite of film students that Ed and I have experienced in the past. Somebody who’s just blindly going forward, too insecure to admit that they’re wrong, and taking the entire crew down the rabbit hole with them. We’ve been on those shoots. I’ve even been that director at times, and we wanted there to be a moment where finally Heather just comes to terms with what’s going down; a sympathetic moment where she just apologizes and says, ‘I just f–ked up. I wish I could change things. It’s my fault.’ A character that you loved to hate up to that point reveals a little bit of her vulnerability and her humanity. That’s what we wanted in the script. So, we sort of found that beat in the evolution of the movie, and we just told Heather basically, ‘Now’s the time where you go off into the woods.’”

Sánchez: “The direction was: You’re not going to make it out of here. This is like an internal monologue. We were directing these actors to almost be like their conscience speaking to them. For Heather, it’s like, ‘You’re responsible for this. You’re the one who brought them out here. You didn’t heed the warnings. You knew this is dangerous and you brought these guys out here. Say your goodbyes. If you want to apologize to people, apologize to people, just basically say goodbye.’ We called it a confessional, your last confessional before you’re going. You’re not going to get out, and hopefully, somebody will find these tapes and will be able to tell your story, but tell your mom goodbye, and tell your family goodbye.”

The movie’s marketing campaign played up the idea that it was a true story. (Photo by William Thomas Cain / Getty Images)

“I knew it was really good. I didn’t know it was going to be sort of indie film iconology throughout the world.”

Sánchez: “Sometime after we shot that scene, I remember putting it on and we were watching it, and it was just like our jaws dropped. I think that was the moment where we were like, ‘Wow, this really could work really, really well.’ It was an immediate reaction. We knew, holy s—t. We didn’t know if people are going to love it, but there’s going to be a big reaction to this. That’s how it was. It was a very simple thing, and that she took it and ran with it and gave us this remarkable performance.”

Myrick: “I knew it was really good. I didn’t know it was going to be sort of indie film iconology throughout the world. So, it was like, ‘This is an awesome performance. There’s a lot of snot that we might have to cut around,’ but the raw emotion… and the composition of the shot, just the sort of the off-frame composition of the shot, felt so authentic, and so real. We were like, ‘This totally rocks.’ We’re two guys shooting a no-budget film in the middle of nowhere. It was something we felt was really powerful, but none of us had any idea how powerful it would end up being.”

The Impact: The Found-Footage Era Is Born

The Blair Witch Project spawned two sequels: Book of Shadows, the rushed-into-production 2000 follow-up that critics savaged and audiences ignored, and 2016’s surprise Blair Witch, which pretended that the previous sequel never existed. The movie’s legacy though, lies not in creating its own horror franchise, but in spawning a new found-footage horror genre; without Blair Witch, it’s hard to imagine we would end up with movies like Creep or Trollhunter, or smart twists on the genre like Paranormal Activity and Unfriended. Myrick and Sánchez are happy to be a part of that legacy, but say the biggest impact of their success is in inspiring young filmmakers to get out into the woods, or onto the streets, or onto a set, and make their movie.

“Literally it was like one of those goofy Hollywood moments where we’re at the sink, and we kind of look up at the mirror and go, ‘OK, man this is it. We are off to the races.’”

Myrick: “We had never been to Sundance before, and that’s sort of the holy grail for a lot of independent filmmakers. When we were accepted it was a huge validation for us as filmmakers, and artists. We weren’t really sure what to expect because as the nervous, self-loathing filmmakers we are we’re like, ‘What if we show up and it’s just crickets, completely empty? Then what?’ We got there, and saw the crowds, and were pleasantly surprised to say the least. It was so busy we almost couldn’t get into the screening ourselves. We were being instructed by our agent at the time, like, ‘You need to leave room for the distributors, for the buyers.’ I said, ‘No, I have got to be in this screening. It’s the Egyptian – Sundance first screening. We’ve got to be inside.’ We did get some seats in there. It was an amazing moment, and I remember Ed and I having a little pep talk in the bathroom at the Egyptian. Literally it was like one of those goofy Hollywood moments where we’re at the sink, and we kind of look up at the mirror and go, ‘OK, man this is it. We are off to the races.’ So, yeah when we got done, and the end came, there was a lot of buzz about the movie, [and] despite it being a midnight showing there were very, very few walkouts, which is pretty typical of Sundance. People are always coming and going out of your screenings. So, almost everybody stayed and the bidding starting immediately that night.”

Paranormal Activity would put its own spin on the found-footage genre. (Photo by ©Paramount Pictures/courtesy Everett Collection)

“I think the hype works for you, up to a point…”

Myrick: “It was an interesting duality going on at times. Especially after the film was out for a while, because I think the hype works for you, up to a point, and then it sort of becomes overhyped. Then it becomes fashionable to be the counter critics of something that comes out. For us as directors, and for the actors, it was almost in a way that we did too good a job making it look absolutely real because so many people attribute their performances – which was very much their acting chops – as something where we just ran them out in the woods, and scared them, and we recorded that. That’s the opposite of what happened. We took them out, but they knew what they were in. They knew they were carrying a GPS around. They knew we were walking through this methodology, this new experimental methodology to make a movie. They were very much cognizant of how to perform, what to do, when to do it, and everything you see is just sheer, raw talent.”

“Just because Stanley Kubrick introduced Steadicam doesn’t mean you should have it in every shot.”

Myrick: “There’s nothing more rewarding than a young filmmaker coming up to me and saying our movie inspired them to make movies. That’s worth the price of admission for me, and to see so many other kinds of films, both bad and good, inspired in some way from what you did is really rewarding. But again, I think every film should be judged on its own merits. Just because Stanley Kubrick introduced Steadicam doesn’t mean you should have it in every shot. There’s going to be good and bad of anything, and there are certainly plenty of bad found-footage films, but every now and then a really good one will come out, and you’re like, ‘Yes, they got it. They nailed it, and it works.’ It’s fun to be part of that evolutionary lineage. I’m constantly surprised by young filmmakers, talented filmmakers, taking what we had done, and doing something a little different with it.”

Josh Leonard and Michael Williams in The Blair Witch Project. (Photo by © Artisan Entertainment/courtesy Everett Collection)

“Regardless of what happened afterwards, we made this little bit of film history.”

Sánchez: “I’m proud of Heather. She should be really proud of what she did. It was just something that regardless of what happened afterwards, or what’s happened since, or whatever, we made this little bit of film history, which is an amazing thing for us to make this $20,000 movie and somehow end up as a classic horror movie. I never in a million years imagined that that’s what would happen to my career. Again, I feel blessed and happy we cast Heather, and so glad she trusted us, and really just knocked it out of the park.”

The Blair Witch Project was released in limited theaters July 14, 1999, and went wide July 30, 1999. Buy or rent it at FandangoNOW.