The Bloody Banality of American Psycho

Bret Easton Ellis' novel anticipated the bleak-humored, pop culture-obsessed sensibilities of the 1990s. But is it any good?

When it was released to thundering controversy and massive hype in 1991, Bret Easton Ellis’ satirical novel American Psycho was a scandal, a pop-culture phenomenon, and a flashpoint for heated arguments about censorship, free expression, misogyny, violence, corporate responsibility, and pornography more than it was a book people might actually read and, even more improbably, enjoy.

That’s because American Psycho is an exceedingly difficult book to read. The novel’s endless parade of explicit, stomach-churning, pornographic, boundary-pushing violence against animals, homeless people, and young women makes it a struggle to finish, especially for delicate souls like myself. But it’s also hard to read because so much of it is boring, tedious, monotonous, and repetitive to the point of perversity.

What makes Bret Easton Ellis’ lurid controversy magnet such a strange, tricky proposition is that its dreariness feels largely intentional. It’s supposed to be shallow, vacuous, and deadeningly repetitive. It’s devoid of insight into the human condition, and it’s filled with deplorable characters who are similar to the point of being interchangeable — one of the novel’s running jokes is that its murderous, woman-and-humanity-hating protagonist and narrator, Patrick Bateman, is constantly mistaken for peers who look, act, dress, and talk the same way because they are all products of the same colleges, prep schools, and social circles.

After suffering through nearly 400 pages of lovingly rendered ultra-violence against women and even more lovingly rendered descriptions of what everyone is wearing, I couldn’t help but feel like we’re not supposed to enjoy the book. Instead, we’re supposed to feel implicated by it, to see our own emptiness reflected in the pulpy story of an inhuman ghoul who comes off as the worst person in the world even before he begins doing unspeakably cruel and deranged things to women — sometimes while they’re dead, and sometimes while they’re still alive — so he can derive an extra level of sadistic pleasure from their agonized screams and soul-consuming terror.

But just because something is part of an intentional satirical strategy — and to give Ellis credit, the book certainly has a consistent authorial vision and voice, in the sense that it makes the same goddamn points over and over again — does not mean it is good.

|

American Psycho feels like the kind of book people buy without any real intention of reading. |

American Psycho feels like the kind of book people buy without any real intention of reading. In that respect, it’s like Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History Of Time (which, alas, wasn’t quite brief enough to actually be read), except that a copy of Hawking’s best-seller strategically placed on a coffee table implicitly conveys that the owner of said copy is intellectually curious enough to want to read a famous book by a smart guy who knows all about science and stuff, while a copy of American Psycho hints that its owner is hip, edgy, unintimidated by the kind of violence not generally seen outside of snuff films, and eager to have an informed opinion in the debate about the novel’s cultural value.

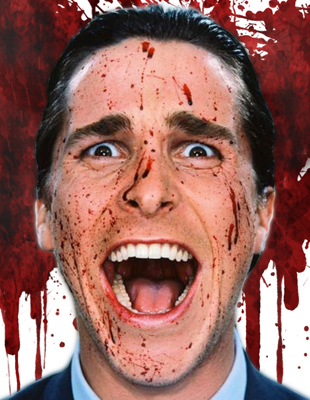

When, after countless false starts, the film was finally adapted by I Shot Andy Warhol director Marry Harron with Christian Bale in the lead in 2000, it officially removed the final reason anyone would possibly subject themselves to reading Ellis’ exploration of the moral corruption of 1980s Manhattan. Harron’s movie is the rare film adaptation of a culturally significant novel that’s widely, if not universally, held to be superior to the text that inspired it. Harron and co-screenwriter Guinevere Turner took what little value there is in Ellis’ book and tightened, sharpened, and amplified it while wisely excluding the enormous amount in the book that’s dull and repugnant.

A literal, exhaustively faithful adaptation of American Psycho would run six hours, be banned in every country, and be unwatchable, but these filmmakers did a spectacular job alchemizing literary dross into cinematic gold. It helped that they were able to show what Ellis could only describe, and when a work is all about superficial appearances, that’s an enormous advantage.

One iconic scene in particular is an especially good example. During a lunch meeting, Patrick Bateman is filled with existential dread when his professional colleagues pull out business cards whose intricate, exquisite details (“bone coloring, Silian Rail lettering” or “eggshell with Romalian type”) both dazzle and enrage him because his card pales in comparison. On the page, the scene falls relatively flat because the details that make the film scene so wonderfully specific in its satire are crowded out by an avalanche of similar details about clothes, electronics, and consumer goods.

American Psycho the novel feels like a bizarre, bloody shotgun marriage between a Brooks Brothers catalogue and sadistic literary porn. Bateman is compelled to identify the designer, style, and features of the clothes of everyone he encounters. A typical early passage, where Bateman checks out three “hardbodies” (his default description for every woman with a nice body, i.e. most of the women in the book) while clubbing with friends reads, “One is wearing a black side-buttoned notched-collar wool jacket, wool-crepe trousers and a fitted cashmere turtleneck, all by Oscar De La Renta; another is wearing a double-breasted coat of wool, mohair and nylon tweed, matching jeans-style pants and a man’s cotton dress shirt, all by Stephen Spouse; the best-looking one is wearing a checked wool jacket and high-waisted wool skirt, both from Barney’s, and a silk blouse by Andra Gabrielle.” Honestly, I found the idea that a man who does not work in fashion would instantly be able to identify so much information about every garment he comes across far more unrealistic than Bateman murdering dozens of people in brutal, perverse, and fairly public ways and never getting caught.

Like Patrick Bateman, Ellis is a big believer in overkill. If he only needs to repeat something five times to really get his point across, Ellis will repeat it a thousand times. If you enjoyed the description of the women’s clothes in the paragraph above, you’re in luck, because there are literally hundreds more passages pretty much exactly like it.

There are telling, novelistic details that succinctly and indelibly capture the world and people they’re describing. Then there are numbingly excessive details, like the ones here, that add little to our understanding of Patrick Bateman’s mind and only serve to pad out the word count to a punishing length. American Psycho doesn’t need an editor: it needs a butcher to lop off its first third.

|

Christian Bale modeled his brilliant performance on Tom Cruise after watching the famed Scientologist on TV with David Letterman. |

And the crazy thing is that the mind-numbing first hundred pages of the book has little actual violence. Bateman’s worst crimes are clearly the ones where he tortures, murders, mutilates and abuses the bodies of young women, sometimes with the assistance of small rodents. Those are genuinely sickening. But his secondary — and still very substantial — crime is that he’s terribly dull, a man without a soul, with a festering sickness where his conscience should be.

Bateman is less a man than a malevolent spirit defined by the labels on his designer clothes, his perfect body and face, the impossibly expensive, exclusive restaurants he frequents, and the soulless, glistening mainstream pop he not only champions but critiques, or rather extols, in three separate manifestos on three of his favorite artists: Whitney Houston, Genesis, and Huey Lewis and The News.

As with everything else in the book, the use of music is heavy-handed and obvious. Because Patrick Bateman lacks a soul, he adores music that reflects his soullessness. In his world, “professional” is the highest possible praise. He says his favorite compact disc is Bruce Willis’ The Return Of Bruno. He’s so unapologetic in his racism (the N word is doled out liberally, along with slurs and epithets of all stripes; to be anything other than rich, white, straight, and male is to be subhuman in his world) that he not only prefers black music to be made by soulless white men; he prefers black music to be made by soulless white men who aren’t even musicians.

Like so much of what we’ll be covering here, American Psycho revels and delights in its own artifice, in its plastic disposability, in the sense that not only does it not chronicle the world as we know it, but it describes a world that could not exist, that does not exist, that functions only as a commentary on pop culture and evil and spiritual emptiness and the dispiriting decadence of a ghoulish ruling class.

Part of this is accomplished by making Bateman the most unreliable of unreliable narrators, a madman who regularly describes things that could only exist in the fevered imagination of a confessed lunatic. Ellis doesn’t delineate between what is real and what is fantasy, and blurs the line further by having people repeatedly profess to have recently dined with people Bateman has described murdering in extensive detail. Bateman also repeatedly talks about his life as if it were a movie; he seems weirdly cognizant that he is a fictional character, a villain in a story instead of an actual human being. The lines blur so extensively that it’s possible to assume — and some have — that none of it is real, that it’s all a pornographic, violent power fantasy from a man who may not be a mass murderer or may not exist at all as anything other than a yuppie boogeyman, the worst of the worst.

American Psycho is seemingly all details, and some of the details are inspired, like the constant references to Les Miserables, a grim yet toe-tapping exploration of the bleak lives of the wretched of the earth enjoyed by people rich enough to afford tickets to its endless Broadway run. Les Miserables is poverty porn. Fittingly, while Bateman’s peers may love Les Miserables , they treat the contemporary descendants of the musical’s subjects with abuse and disdain, and Bateman, of course, treats them much worse, with murderous barbarity.

Time has given some of the novel’s clumsy pop-culture references a new resonance. Christian Bale famously modeled his brilliant, hilarious, star-making performance on Tom Cruise after watching the famed Scientologist on television with David Letterman. In American Psycho (where Bateman’s favorite show is Late Night With David Letterman) the protagonist only really looks up to two non-musicians (Huey Lewis is sacred, the rest of humanity is scum). One is Tom Cruise, who lives in the penthouse of his building and who he fumblingly compliments for his performance in Bartender (which Bateman mistakes as the title for Cocktail). The other rich, famous alpha-male who inspires a Wayne-and-Garth-style “We’re not worthy!” deference in this otherwise supremely arrogant and evil man is a Gordon Gekko-like exemplar of cheesy 1980s greed, the crazy-haired TV clown who is currently the most talked about man in the country: Donald J. Trump.

|

Donald Trump and (now ex-) wife Ivana are referenced regularly by Bateman, always with an uncharacteristic reverence. |

Trump is as much a fixture in the book as Les Miserables. He and (now ex-) wife Ivana are referenced regularly by Bateman, always with an uncharacteristic reverence. They are god and goddess in his world, or at least king and queen. Late in the book, Bateman, deep into a downward spiral of madness, gazes adoringly at a Trump building glistening in the sunlight and contemplates pulling out his gun and blowing away a pair of African-American hustlers running a three-card monte game. The scene eerily mirrors the fears of contemporary Trump detractors.

American Psycho doesn’t really break through the tedium until Bateman’s mask of sanity begins to slip. At this point, interchangeable conversations about fashion give way to interchangeable murders and freak-outs that are at least animated by a sleazy, lurid energy, and the book begins to develop a dark, shadowy momentum.

American Psycho gets more interesting as it goes along, but it remains shapeless, clumsy, and for the most part, desperately unfunny, especially compared to the film adaptation. Ellis’ stylistic gimmickry and game-playing — like having the narration switch briefly from first to third person late in the book, as Bateman’s desperation mounts and the walls seem to close in — is far more compelling than his prose.

Ellis’ American Psycho is far more interesting to joke about and think about and talk about and analyze than it is to read. The book is noteworthy and important more than it’s good, and the manic, non-stop pop-culture references, blurring between reality and fantasy, and postmodern elements found in it would be realized far more artfully and entertainingly by other books, television shows, movies, and music in the years to follow, including the film version of American Psycho, which took the book’s ugly clay and transformed it into a gorgeous sculpture of smart-ass cinematic pop art.

A quarter century after its release, American Psycho remains a scandal, controversy, pop-culture phenomenon, and a flashpoint for heated argument arguments about censorship, free expression, misogyny, violence and pornography more than a book people might actually read, and even more improbably, enjoy.

Yet, all these years later, the book retains its power to shock and offend. That may be a bit of a dubious distinction, but I suspect it’s one a provocateur like Ellis would embrace. Then again, I was repulsed by the gory, visceral ugliness of its violence and misogyny and offended in large part by the poor quality of its writing and construction, which I suspect Ellis would find considerably less flattering.

Nathan Rabin if a freelance writer, columnist, the first head writer of The A.V. Club and the author of four books, most recently Weird Al: The Book (with “Weird Al” Yankovic) and You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me.

Follow Nathan on Twitter: @NathanRabin