SUNDANCE: Interview With "American Hardcore"’s Paul Rachman and Steven Blush

Filmmaker Paul Rachman and author Steven Blush had a mission when they began working on "American Hardcore," a chronicle of the American punk scene of the early 1980s, which debuted at Sundance.

"I told Steve, ‘We need to make the "Woodstock" of hardcore, the definitive film to eternally explain what this moment in history was,’" Rachman said.

"American Hardcore," based on Blush’s book of the same name, has been four years in the making. The film features archival footage and incisive interviews with some of the key musicians and fans of the era, including Henry Rollins, Ian MacKaye, H.R. of the Bad Brains, and even Moby.

Rachman and Blush make plain that they feel hardcore was not simply louder and faster punk rock, but a political statement — a reaction many suburban kids had to their immediate surroundings, and to the direction of national politics.

"The movie is a time capsule of American history as well as a music documentary," Rachman said. "It’s a social statement. It’s no coincidence this scene happened at a time when Ronald Reagan was president and was reinstituting these conservative values. [Hardcore] was a raw reaction to that. It wasn’t an organized, intelligent reaction, it was instinctual."

But nobody would care about the politics of this small musical movement if the bands themselves weren’t so compelling. Groups like Minor Threat, Black Flag, and the Bad Brains, who were underdocumented by the mainstream media in their primes, have continued to influence hundreds of bands in the years since the demise of hardcore.

"These bands never got their due," Blush said. "I’ve always believed hardcore was a sleeping giant. These are the bands that influenced everybody. The kids all know about these bands, and yet nobody really talked about it and nobody really wrote about it and that was the impetus for the book and the film as well."

Hardcore also influenced fashion, and introduced stagediving and slamdancing to the American scene. But its biggest influence may have been the loose network of fans who helped set up gigs and let the bands crash on their floors during the long, arduous tours across the country, Blush said.

"These were the bands that started a lot of the independent network that we now see today, the whole idea of putting out your own record, going on your own tour, DIY [do it yourself]," he said.

On a local level, kids gathered around hardcore in small but tight-knit units, Blush said.

"[DC] was a very small community," he said. "Whether you were really close to them, or you were in awe of them sitting in the back of a crowd, you were part of that community. It wasn’t like, ‘Come in and join us,’ but if you were there, you earned respect in that way. It was tacit approval. We weren’t a coherent movement or a coherent scene, but we were a fierce scene."

Punks attracted a lot of negative attention from other teens and the police; the straight edge movement, which emphasized abstinence from the use of drugs or alcohol, was a two-pronged reaction to teen substance abuse and the idea that punks couldn’t control themselves.

"These kids are talking about being young and hostile and sober," Blush said. "And it’s really an incredible thing. There’s nothing more radical than these crazy looking punk rock kids who were all sober, because nobody could say anything to you at that point."

In the early 1980s, Blush was booking shows in the Washington, DC area, and Rachman shot videos for the Bad Brains and Boston’s Gang Green, so interview access to the artists was not an issue.

"Steve and I were part of the scene, so our interviews were really conversations," Rachman said. "We sat down with these people and just talked about back in the day. We got the trust from them, the trust that we would tell their story the way it needs to be told. And the story is told by them, and we edited it to tell their story from beginning to end."

And unlike many music docs, "American Hardcore" didn’t require a lot of licensing of the music.

"There’s no major publishers and record companies involved," Rachman said. "We’re dealing with guys who wrote the songs. If you want Minor Threat, you talk to Ian MacKaye, and that’s it. There’s nothing more."

Finding vintage footage of hardcore shows proved to be more of a challenge, however. Because video technology was not the best, and because the kids doing the shooting were not filmmakers per se, much of the footage is very raw; furthermore, it wasn’t necessarily well-preserved, Blush said.

"This stuff was very primal, very primitive," he said. "It’s almost like archeology. We had stuff in [the film] that’s second generation VHS tapes. I had to dig through boxes and dust off things that were in people’s basements, things were waterlogged. I’ve found tapes where there’s a concert and then there’s an episode of a TV show and then there’s the rest of the concert."

Rachman was one of the filmmakers who founded Slamdance in 1994, and continues to work as Slamdance’s East Coast managing director and helps with programming. A slot in the Slamdance lineup was planned, but the late acceptance of "American Hardcore" to Sundance meant that the film could be seen by a more general audience that might be unfamiliar with the music.

"[We felt], ‘let’s bring it to Sundance and preach to the unconverted,’" Rachman said

Plus, Slamdance is a film festival for first time directors, which Rachman is not.

"If ‘American Hardcore’ had played at Slamdance, I was effectively taking a spot away from [a filmmaker] who really deserves that slot, and what the Slamdance mission is about," Rachman said.

The films that play at Slamdance have no distributors, and are modestly budgeted, generally under $1 million, and usually under $100,000. The idea of the festival was to give a showcase to inexperienced filmmakers in a way that they wouldn’t be lost in the shuffle at Sundance, Rachman said.

"Slamdance offers a simpler, more intimate environment, and it’s been a really great stepping stone for a lot of filmmakers," he said. "We started it because we wanted to be part of Sundance, and our way of being part of Sundance was starting Slamdance. It was a kind of punk attitude doing it.

"Slamdance comes to Sundance because everybody in the world comes to Sundance," he said. "The missions are a little different, the results are a little different. [But] both festivals do this because they love independent film. I’m still involved with Slamdance, I’ll continue to be involved with Slamdance, and I’ll probably be sweeping the floor next year."

Blush said he was particularly impressed with Sundance’s emphasis on staying true to one’s art.

"One thing I really like about Sundance, even though there’s a corporate sheen, they’re all about pushing yourself as an artist," he said. "It’s nice to hear that. There is a fierce independent spirit going on here. I’ve got to give it to this festival for pushing that. All in all, it’s been a great experience."

And staying true to one’s ideals was one of the most important tenets of hardcore, Blush said.

"That’s what the music was all about," Blush said. "All these bands, they weren’t experts, they weren’t great musicians, they just picked up a guitar and played it, and that is the essence of ‘American Hardcore.’"

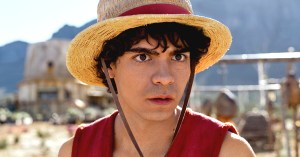

Photo (left to right): Steven Blush and Paul Rachman

Check out Sundance features by Rotten Tomatoes:

• Sundance Full Coverage

• Sundance Blog

• Sundance Discussion