RT-UK: Leonardo DiCaprio Interview

Leonardo DiCaprio switches continents for Blood Diamond and speaks exclusively to RT-UK’s Joe Utichi

Nine years ago, we’re reckoning, the hour that we spent with Leonardo DiCaprio recently wouldn’t have been possible. Titanic had just come out and Leo-mania saw a bumper year for security guards. In the time that followed DiCaprio seemed keen to grow up, tackling ever more challenging and rewarding roles. He hadn’t contemplated retirement after Titanic, as was “revealed” earlier this week; instead, he tells us, he just wanted to take a break to, in his own words, “let that ship pass by.”

Nine years ago, we’re reckoning, the hour that we spent with Leonardo DiCaprio recently wouldn’t have been possible. Titanic had just come out and Leo-mania saw a bumper year for security guards. In the time that followed DiCaprio seemed keen to grow up, tackling ever more challenging and rewarding roles. He hadn’t contemplated retirement after Titanic, as was “revealed” earlier this week; instead, he tells us, he just wanted to take a break to, in his own words, “let that ship pass by.”

This month sees the release of Blood Diamond, directed by Edward Zwick and co-starring Jennifer Connelly and Djimon Hounsou. In the film, DiCaprio plays a South African diamond smuggler who becomes involved in an operation to move a giant pink conflict stone across the border for sale on the international market. So for sixty minutes he graciously agreed to sit down exclusively with Rotten Tomatoes UK – while in LA his name was being announced as a Best Actor nominee for this years Oscars – and tell us about the film and his role.

RT-UK: So the Oscar nominations are out in half an hour; did you get any sort-of advance warning or will you learn at the same time as us?

Leonardo DiCaprio: No advance warning. I’ll take a lunch break and see what happens; it’s on at half-past one, right? But I have no idea. I think no-one knows; I guess the excitement and the fun of that awards ceremony all together is that it’s the unpredictability of what may happen either with the nominations or who’ll win that gets people excited, you know.

RT-UK: Does it still get you excited? You’re a bit of a dab hand at this stage, aren’t you?

LD: Yeah, I mean, definitely. It’s something, though, that I’ve learned more and more you have absolutely no control over. But sure, you know, it’s not something that I’m going to reject if it happens, for sure!

Honestly, it’s a bad answer but it’s the truth, it’s a nice thing to be recognised like that. It really is. Truly, to put a lot of hard work and effort into a character like this and then for it to be recognised, how can it not be nice? It’s certainly not something I expect by any means, or that we strive for through the pre-production process, or even the filming process. It’s one of those things that the more I’ve acted I’ve realised I a) have no control of and b) no way of really quite understanding how people will react to anything I do or any movie I do. If every actor, every studio had that magic formula we’d all be making critically acclaimed multi-billion-dollar hits every time we made a movie. There are so many intangible forces that come into play when making a film. I honestly have no idea what the public will ultimately thing of something I’ll do, let alone critics. It’s something I think continues to mystify all of us!

RT-UK: Which of your two roles would you rather be up for nomination?

LD: I couldn’t possibly say that! To be honest, I couldn’t be more proud of these two roles I’ve done, the release of which has come about I guess as a result of Scorsese’s editing process, he has a really long one, they’ve coincidentally come out at the same time. And it’s happened before; I did Gangs of New York and then I did Catch Me if You Can and I think they came out in the same month. Here I did The Departed and then went off to Africa and did a whole other movie and they came out at the same time because Scorsese has a very, very long editing process.

RT-UK: With this role and The Departed do you feel that you’ve finally shed the more romantic, heart-throb image that’s followed you for a while?

LD: You know, I’m never really conscious of saying, “I’m going to take on a specific role to combat a certain image in the public eye.” I think that’s pretty manipulative and transparent to the public anyway. And I’m, by the way, open to doing any kind of role and any kind of genre as long as it’s interesting and as long as I feel it could be a great character to play. I never take into my own personal opinions or my own public image into account when I chose movie roles.

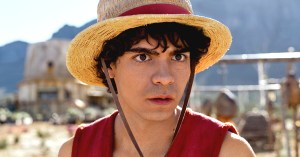

A still from Blood Diamond

RT-UK: Was it refreshing being able to walk around parts of Africa where people don’t know you?

LD: Certainly I was more anonymous there, for sure, but I did get recognised there as well. Ultimately I hate even complaining about it, I hate complaining about paparazzi, I hate complaining about being recognised, because if I ultimately didn’t want to be an actor or in the public eye, I would quit doing what I do. That’s not the reason I do it, but I love the work so much that it’s worth it. But yeah, in Africa I was definitely more anonymous.

RT-UK: How long did you spend in Africa?

LD: I spent five or six months in Africa. I wanted to go there as early as I possibly could. I’d never spent more than a month in Africa, I went to a place called Jabuti which was the hottest inhabited place on earth. I was there for one week. Going to South Africa was an incredibly experience for me. Not just learning about the history and the culture, the attitudes of the people there… I had to go there early. It would have been a complete disaster if I’d tried to do that type of research with reading material or over the phone, I had to kind-of immerse myself in that environment otherwise I wouldn’t at all have been able to capture any kind of reality with this guy.

We honestly didn’t have much time, we were shooting constantly and rehearsing constantly, but I did get to go on a couple of safaris which was pretty incredible. It was amazing to see, you know, two male lions devour a wildebeest carcass and having these cubs come out of the bush and surround this carcass like ants on a bit of candy was unbelievable.

RT-UK: What was being there and witnessing first hand the harsh realities of the continent like?

LD: Growing up in the Western World and seeing some of the things we saw – not to mention the immense natural beauty of Africa – but to see the conditions people live in there everyday and how they’ve somehow maintained to have such an amazingly positive attitude and outlook on life was pretty inspiring for all of us. We all have our own private stories and feelings on the matter but to put it bluntly it was the spirit and the feelings of the people that was the most astounding and moving for me as a person to witness. We shot in areas of Mozambique where four out of ten people had the HIV virus. There was poverty everywhere; no-one had clean water. And yet they maintained an attitude of just being happy to be alive. It’s a place that deserves the Western World’s support as much as possible.

RT-UK: Did being in South Africa give you some sense of – for want of a better word – the plight of white South Africans? They’re seeing their privilege taken away at the moment, really…

LD: It continues to be a very confusing issue to me; South Africa and the culture there. Through truth and reconciliation, which I think is a very therapeutic thing for everyone involved, I think they’re still learning to coexist right now. This is that period and time that will determine how the future’s laid out. But all I have to say is it was a very foreign environment for me and some of the things that I saw there were very jarring. I’ll keep some of my thoughts personal but it was an environment I wasn’t comfortable with.

RT-UK: Was it tough dealing with material that sees your character provoke and condescend Djimon Hounsou’s character? Is that related to feelings of role-playing in South Africa?

LD: Certainly. Being in an environment like that where you’re surrounded by people who are still suffering from the economic instability there, and still suffering from the class structure, to play a character who is taking advantage of another African man, surrounded by an entirely African crew, posed some uncomfortable moments. Even as much as you’re in character, and you’re trying to become that guy, it’s weird, not to mention my affinity and kinship and the brotherhood I have with Djimon as a human being, and the friends that we’d became, it posed some very surreal, uncomfortable moments for us as actors. Fundamentally, we understood we were making a movie at the end of the day, and this other side, the negative side, needed to be portrayed realistically – and that was the case.

RT-UK: Djimon is obviously from Africa – what was it like for him to be back to shoot this movie?

LD: Well, you know, being an African man who moved to America and then went back to Africa to make a movie of this subject matter there was a certain pathos that I think he naturally embodied; a certain instinct and passion that I certainly felt from him as an actor. That’s not to say, of course, that the man didn’t do a certain amount of work in learning the local accent and transforming himself but there was a certain instinct that I certainly felt being around him every day and working alongside him that was very carnal, you know, and deep-rooted. It came from the gut and I think it shows up on screen.

A still from Blood Diamond

RT-UK: Does location work, as I’d imagine formed the bulk of Blood Diamond, lend itself to the relationships you guys share on-set? It seems like you bonded closely with both Djimon and Jennifer Connelly…

LD: There is a certain element of camaraderie, I think, that exists on location when you’re forced to be in each other’s space constantly. The film takes centre-focus with everyone and you don’t go back home to your comfortable lifestyle and your daily ritual. Certainly in a place like Africa, not just the environment but the political landscape was surrounding us all the time and the issues were there; we could draw upon stories from other people and I felt that we were constantly sharing information about the place that we were filming in. I think that affected all of our characters and affected our relationships with each other as characters, too.

RT-UK: How significant was taking on the South African accent in terms of leading you into the character?

LD: It was a completely foreign and alien sound for me, the South African sound. I went early because, having not spent a lot of time in Africa, I needed to lock down the accent as best I could and try and get the general attitudes of some of these mercenaries; these soldiers of fortune. These men that fought wars in Angola, have seen some of the atrocities we’re displaying to try and capture their bitterness and mixed-emotions towards the continent that they’re from. I think that spending a lot of time with these guys absolutely, fundamentally shaped the character for me. It was their stories that I tried to embrace and take on as my own for Danny.

RT-UK: How did you gain the soldiers’ confidence? Was it about getting down and dirty with them?

LD: You hit the nail on the head, yeah! Initially going there there’s a hardened shell that surrounds most of these guys. And, you know, I was pretty surprised coming from America and I think I incorporated a line, “You Americans love to talk about your feelings,” from my experiences hanging out with these South African folks. Because it was very hard for them to divulge anything about their attitudes about Africa or their mixed emotions about the politics there or their experiences at war and what it was like for them and what they were feeling. It did take a certain amount of taking them out to various bars and, you know, getting them drunk and rehashing past demons. That was some of the most beneficial stuff for me; it helped me shape my character and made me understand some of the emotional turmoil that my character had gone through?

RT-UK: Was it an undercover operation in a way because of your fame?

LD: You mean did I go in disguise?

RT-UK: Yeah, were you smuggled in?!

LD: Smuggled into a bar? No, I just kinda walked in!

RT-UK: This is your first “political” movie – are you looking for other projects like this? Does the fact that you’re making these kinds of movies perhaps reflect the end of a personal journey of yours?

LD: You know the truth of the matter is this; I never look for films specifically… First off, let’s backtrack and say that it’s very hard to impose your beliefs or a specific message about any given movie. I think that audiences always extract what they want from a film even if something isn’t overtly political. They may or may not get it, and it’s hard to control that. But that being said, I never look for a movie specifically for that reason, because ultimately if the fundamentals of the character and the script and the director aren’t there, it makes it a moot point.

I would love to do a movie about environmental issues. I would love to do a movie about global warming, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to rush out and go do a film just because that’s the theme. It has to be a quality piece of art. That being said again, I would love to do another movie with more of a modern political message like this. And if this movie breaks even around the world, or does financially well, that will only encourage studios to take more chances with films that have very topical, pertinent issues.

And hopefully the film goes into enough profit to the point where studios will feel comfortable doing more movies and develop more projects like this, because I think this really is a great outlet to get people to be educated about issues.

People all the time ask me about even this movie, “Do you think it’s made any difference?” And my answer is, “It already has.” Even before the movie came out, diamond companies have been more transparent in their talks about how the way businesses run. The Kimberley process has been re-examined and in the media it’s a hot topic.

A still from Blood Diamond

RT-UK: Have you ever bought diamonds for anybody? If so, were you aware of their origins?

LD: Sure, I’ve bought diamonds in the past. Before learning about conflict diamonds and their devastating impact on places like Sierra Leone I basically knew the tagline of what a conflict stone was or the term, “blood diamond.” I was pretty-much unfamiliar with the ramifications of some of the events that have gone on and I the devastating impact that it’s had on countries in Africa. Millions of people have been displaced, you know, millions of lives lost. If you see the movie you obviously see there’s some pretty horrific events and, by the way, I’d like to mention none of it is glorified or exaggerated by any means.

Would I ever buy a diamond again? If I were ever to buy a diamond again I’d make sure it’s a conflict-free diamond and I would get it certified by the dealer I bought it from, that’s for damn sure.

RT-UK: Did what you learned and saw make you want to take action?

LD: Yes, and I have since. I’ve done work with Save Our Souls, the organisation out their in Mozambique. I’ve contributed to them and I think we’re all continuing to work with organisations like Amnesty International and Global Witness to get the message out there about conflict diamonds. Jennifer and Djimon, I know have a long history of work in Africa.

Blood Diamond arrives in UK cinemas on January 26th. It is out now in the US.