Anton Corbijn on Control: The RT Interview

The photographer-turned-director discusses his stunning Ian Curtis biopic.

Anton Corbijn was a 24-year-old professional photographer when he decided to move from his native Holland to England, partly to meet and shoot some of his favorite musicians. One such band was the post-punk outfit Joy Division, who Corbijn met within two weeks of his arrival. A subsequent photo shoot in a London subway station became one of the most iconic photos of the group, whose deep, melancholy music became more notorious when lead singer Ian Curtis committed suicide on the eve of the band’s first U.S. tour.

After Curtis’ death, Joy Division became New Order, and Corbijn went on to an acclaimed career in photography and directing music videos (including Depeche Mode’s “Personal Jesus,” Henry Rollins’ “Liar,” and Nirvana’s “Heart-Shaped Box”). When Corbijn’s attention turned to cinema, he initially turned down the chance to make Control — which is based on the memoir Touching from a Distance, by Ian’s widow Deborah Curtis — but came back to the film after realizing that his own emotional attachment to the story lingered, decades later.

The result is a true passion project, crafted with a photographer’s eye in starkly beautiful black and white shades. While known to use monochrome palettes in much of his still work, Corbijn says the cinematic choice simply made sense, as his recollections of Joy Division (and post-punk journalism in the late 1970s) are all black and white. Likewise, the stars seem to have aligned when it comes to Control‘s stirring central performance by newcomer Sam Riley, whose spot-on resemblance to Curtis in both image and sound lend Corbijn’s film an element of painful authenticity. Control deservingly nabbed directorial and acting honors at the Cannes and Edinburgh film festivals, and opens in limited release this week.

Rotten Tomatoes: How did you first meet Ian Curtis and Joy Division?

Anton Corbijn: Well, I was a photographer and I loved their music. I thought they were an amazing band, that’s why I moved from Holland to England. And I met up with them within two weeks of moving to England, and I did this picture that became later well known. But I was a photographer about seven years before I met Joy Division, so it was not the first thing that I did but it was the first thing I did when I moved to England.

RT: How did you prepare — or did you prepare at all — for backlash from Joy Division fans?

AC: No, not really. The thing is I knew I wanted to be correct, from my perspective, because I’d seen Joy Division live, and there are also visual references to their performances, so you knew that you could really work on it to get this correct. And that way I knew I would satisfy Joy Division fans who are anal about this sort of thing. So we just made sure we got it right; the other bits, with Ian [Curtis], there are no references to so that’s all about talking to people and getting it right. That was a very important part of the story, if not the most important part.

RT: The use of black and white is especially powerful in Control. Can you talk about why that choice was appropriate?

AC: I think it’s beneficial to the film, in a sense, because it’s very dramatic, the use of black and white in a film. But the real reason I chose it is that all my memories of that period and Joy Division in particular are black and white memories. If you go back to try to find official references, old photographs, of Joy Division, I would say without exception you’re going to find them to be in black and white. So combine that with their album sleeves being in black and white, the clothing being not very bright in the sense of colors, it just felt appropriate.

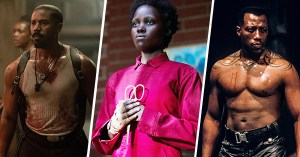

Sam Riley as Ian Curtis in Control

RT: What was it like to transition from photojournalist to artist?

AC: Well you know, all these changes evolve over time, and quite slowly. My photography changed from being more documentary-like to arranging things more and that came into being partly because I started doing music videos, and I incorporated some things from the music videos into my photography again, by arranging things more. So my later work is more conceptual, and I also do design and both graphic and stasis, and I’m keen on trying other forms of visual discipline; a film is such a big thing that you tend to push it in front of you, you don’t think you can do it, you don’t also think that you can find the time to do it — it will take a year of your life, at least, to make a film. So it’s very hard to commit to that while you’re working on something else.

A lot of scripts that I was given I didn’t feel were right for me, because I didn’t feel anything for them — I didn’t feel like I was going to change in life and start directing. But then this came along. Having initially said no, I came back to it because I felt it resonated so much with a lot of my life, especially when I was younger, so I felt that I had at least an emotional connection to the story that would maybe compensate for the lack of knowledge of filmmaking.

RT: Seeing as this is your first feature film, and first time directors often start with passion projects, was that a factor in determining what your first film would be?

AC: I think if you don’t feel passionate about the first movie you’re doing, in the end the project will lack something because you don’t have enough experience to make the movie something special. I think if you have the passion, that becomes such a drive for everything else that you can feel it in the movie, and it also drives other people that you work with in other departments of filmmaking. For my next project I can do a story that I don’t feel emotionally connected to — because you learn so much from making your first film that you learn the craftsmanship, that you can also apply to something that you think is a great story, without having the personal emotional connection to it.

Joy Division signs with Factory Records’ Tony Wilson in Control

RT: Are you deciding on your next project already?

AC: Well I don’t have the story yet, but I have the idea of the story.

RT: Will you write it yourself?

AC: No, I need somebody to either work with me or work for me, as it were.

RT: I saw in the press notes you mentioned possibly looking into a thriller.

AC: Right. I didn’t realize it was in the press notes! [Laughs.] So much for trying to keep it a secret!

RT: Do you find that a lot of people that have seen the movie so far are enthusiastic about it?

AC: Yeah, I mean I just keep my fingers crossed. Now we’re getting a bunch of people who say they really hate it but it’s been really positive. Also there are a lot of women, I have to say, which I really like because initially people said “Oh, it’s going to be a biopic of Joy Division,” which it really isn’t of course. But when you say that, you expect a guy’s film because it’s a band, but now I find that women really take to the story because it’s really a tragic love story, that’s what the story’s about. It’s not a movie about Joy Division. I saw people at the screening that I knew, from England, and they really loved it. It’s just unbelievable. It’s really so powerful, the performances are so compelling and it’s a very sad ending.

RT: You should claim credit for a lot of that praise. The compositions are beautiful —

AC: Yeah, but that’s easy! I think if I lay any claim it’s that I managed to work well with the actors, and that for me is the real work. That was new for me, and that’s what I put all my energy into. The look of it, I knew I could do that. Anybody can sort of do that.

Sam Riley as Ian Curtis in Control

RT: Is it strange getting all this attention now as a director, when you’ve been directing music videos for a while?

AC: Yeah, but music videos are…they’re little hobbies, in a way. It’s not a matter of life and death, and I think filmmaking is much more serious; you can change people’s perception of things and really have an emotional impact. It’s very hard to do that with music videos. There’s only one music video that had an emotional impact on me, and that’s “Hurt” by Johnny Cash. That’s exceptional. There is no music video I can think of apart from that one that really reaches you inside.

RT: Do you think that’s something that’s really dismissed too easily with music videos, that they’re not taken very seriously?

AC: Yes, I think there was a period in the 1980s and 1990s, that it was an art form to some people. But now — well actually I don’t watch them anymore, I shouldn’t comment on it. But it doesn’t mean much in my life.

RT: This is probably one of my favorite films of the year so far.

AC: Thank you. [Smiles] It’s a shame it’s not December.

RT: Have you begun thinking about awards season?

AC: Well, we got some awards already, but…you don’t make a film for awards. We managed at the Edinburgh Film Festival to get best film, and best actor for Sam [Riley] so that was beautiful. And at Cannes we got some stuff [Control won awards for best European film, best film in the Director’s Fortnight sidebar, and best first or second directed feature]. So, it’s all great. When you make a film without any of these expectations, it’s all beautiful, and that’s what happened. We had no expectations; we just wanted to make this film.

Control is out this week in limited release and is Certified Fresh with a 90 percent Tomatometer.