This week’s release of Halloween marks Rob Zombie‘s third full-length directorial effort. Here at Total Recall, we thought we’d look back at the movies that have inspired the former Robert Cummings’ work on House of 1,000 Corpses (15 percent on the Tomatometer) and The Devil’s Rejects (53 percent).

Under the “Hellbilly Deluxe” trappings, Zombie is a true cinephile at heart: he’s as likely to find inspiration in the works of Martin Scorsese and Sam Peckinpah as he is in the grimy world of low-rent 1970s drive-in fare. True, Zombie looks to the dark side for inspiration, but he’s also informed by works with gallows humor.

Growing up in blue-collar Haverhill, Mass., the little Zombie enjoyed a steady TV diet of the

Marx Brothers. The anarchic antics of

Groucho,

Chico, and

Harpo obviously left an impression, as Zombie would christen his antiheros in

House of 1000 Corpses and

The Devils Rejects Captain Spaulding, Rufus Firefly, and Otis Driftwood — each names of characters played by Groucho Marx. It may seem like an odd choice, but the Marxes always maintained a subversive appeal. As Roger Ebert notes in his review of

Duck Soup, “Although they were not taken as seriously, they were as surrealist as Dali, as shocking as Stravinsky, as verbally outrageous as Gertrude Stein, as alienated as Kafka.”

The Brothers’ films are generally more like a string of gags than cohesive narratives, and some of their shtick — like the long musical interludes in A Night at the Opera — can seem hopelessly dated. But Groucho’s double-entendre-laden one-liners, Chico’s hustler persona, and Harpo’s deft physical comedy still contain a hilarious, rebellious edge. If you’ve never seen the Brothers in action, Duck Soup (94 percent) and A Night at the Opera (97 percent) are perhaps the best places to start. Of the latter, Peter Bradshaw of London’s Guardian wrote, “Their sheer irreverence, exuberance and verbal comic genius are marvelous.”

In

Corpses and

Rejects, Captain Spaulding has “Love” and “Hate” tattooed on his knuckles — a direct reference to

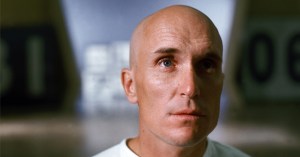

Robert Mitchum‘s iconic Harry Powell, the evil false prophet from

The Night of the Hunter. In his only directorial effort,

Charles Laughton borrowed heavily from the angular, shadowy ambience of the German Expressionist classic

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (100 percent). Still, there’s an unreality to

The Night of the Hunter that make it a singular viewing experience; it has a haunted, surreal ambience you won’t see anywhere outside of a

Bjork video. It’s also viscerally frightening, and Robert Mitchum is at his demonic best here, playing an ex-con who learned of a stash of money from his cellmate, and proceeds to ingratiate himself with the man’s family. But the children are not fooled by Powell’s smooth talk, and flee across an ominous countryside, with Powell in pursuit. Eventually, they are taken in by Rachel Cooper (

Lillian Gish), the guardian of a group of troubled orphans. The climax has an apocalyptic air, as Gish tells the story of mean ol’ King Herod while pumping her shotgun.

Filmmakers like Spike Lee (in Do the Right Thing, 100 percent) and the Coen Brothers (in The Big Lebowski, 83 percent) have borrowed dialogue from Hunter, and the excellent-yet-ignored Undertow (57 percent) re-imagined its plot for contemporary times. Hunter is at 100 percent on the Tomatometer; Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader calls Hunter “an enduring masterpiece — dark, deep, beautiful, aglow… Ultimately the source of its style and power is mysterious — it is a film without precedents, and without any real equals.” Shawn Levy from the Oregonian calls it “As crude, direct, rattling, mystifying and exciting as American movies get.”

If

Night of the Hunter spawned few direct imitators, the opposite can be said of

John Carpenter‘s original

Halloween. Yet seven sequels and thousands of knockoffs haven’t dulled the impact of the original slasher flick, perhaps because it’s not really a slasher film at all. Like

Psycho (98 percent), it generates its scares by maintaining an almost unbearable level of suspense.

Halloween is the story of Michael Myers, who committed unspeakable acts of violence as a child and has escaped from a mental hospital, ready to kill again. Possessing a wicked sense of humor,

Halloween lacks the self-seriousness that would infect later horror films. As sharp as

Scream was,

Halloween parodied horror tropes just as effectively, even while inventing them. At 89 percent on the Tomatometer, “

Halloween remains untouched,” wrote James Berardinelli of ReelViews, “a modern classic of the most horrific kind.” “They should have broken the mold when they released

Halloween, for when it comes to escaped-maniacs-on-the-loose films this one’s the real deal,” wrote Marjorie Baumgarten of the Austin Chronicle.

It’s unlikely that Zombie’s Halloween will be the enduring classic the original has become, but that would be holding him to an impossibly high standard. Regardless, don’t let Zombie’s new remake and horror-film reputation fool you; there’s a much broader history of cinema informing his movies than their shock-and-scare heavy execution might suggest.